Euphoric Halakha for and by Trans Jews

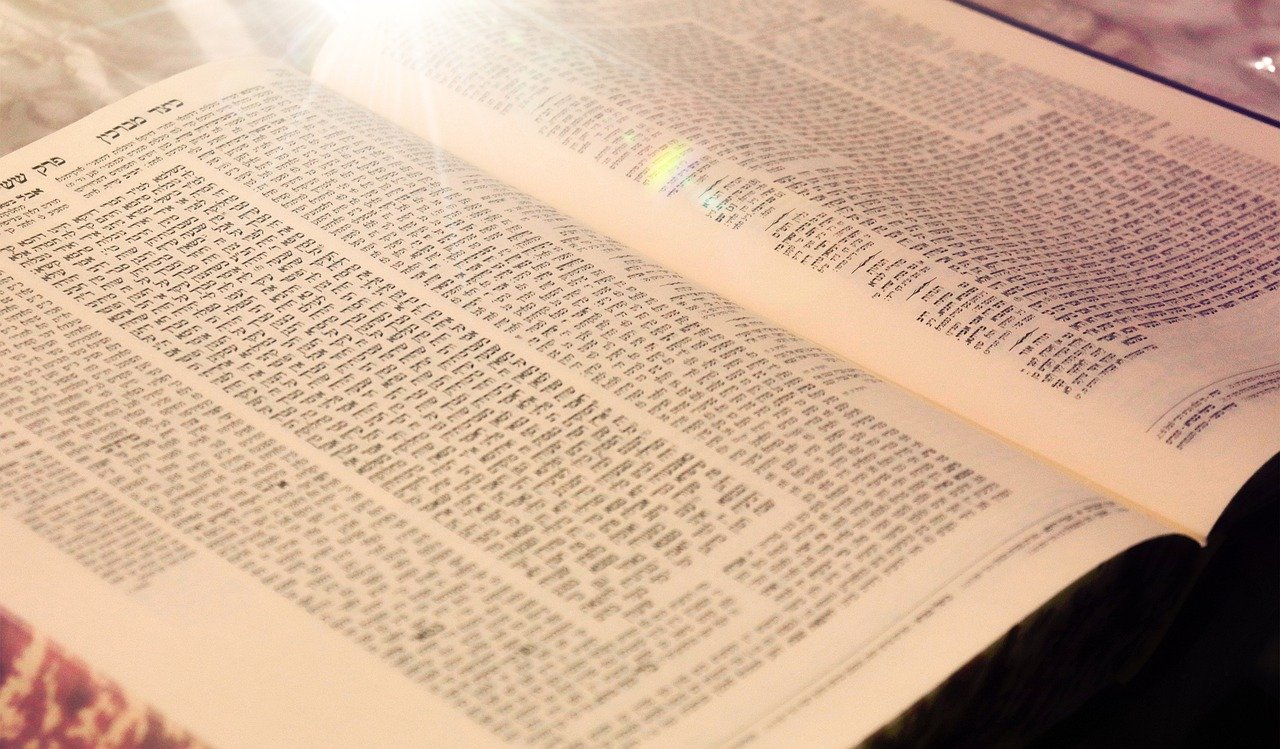

In honor of Shavuot, a holiday celebrating receiving the Torah, I spoke with Rabbi Becky Silverstein and Laynie Soloman about the ways they are helping queer and trans Jews receive and create Torah in new ways.

The Trans Halakha Project, housed at Svara: A Traditionally Radical Yeshiva, aims to provide trans Jews with a framework within which to develop meaningful Jewish practice that affirms their identities as trans folks. Silverstein and Soloman share the ways that Jewish learning that includes queer and trans Jews not only enriches the lives of those individuals, but ripples outward to strengthen surrounding communities. The word Halakha itself comes from the hebrew root hay lamed caf, which means to walk. This project reveals the power in a Jewish practice that is borne out of the way real people walk through the world.

Abigail Fisher: What does Halakha (Jewish Law) mean to you and how would you define it for the purposes of this project?

Laynie Soloman: Halakha means a lot of things to a lot of different people, but Halakha for us is a language of Jewish action and expression, a way we express our values. That language is situated within a worldview. The worldview that the Trans Halakha Project is situated in is trans experiences as the foreground for how we use that language, what that language is saying. But essentially Halakha is the way we talk about and do Jewish in the world.

What role has Halakha played in your own lives?

Rabbi Becky Silverstein: I grew up in a reform but mostly secular reform home, without a relationship to Halakha of any sort. I’m not even sure when I first heard the word “Halakha.” My relationship with Halakha has been a personal one, one that is in constant development as I continue to learn about what the Halakhic system is in the most traditional sense: as in this is how the Torah has been translated into action through the views of the ancient Rabbis and the not-so-ancient Rabbis. I would say that my relationship to Halakha right now is one of continued learning, and of an experimentation process. [It] is a way to deepen my learning, to focus on my relationship to myself and my family and God and Jewish community.

LS: The first time I came into contact with the idea of Halakha as a word or an enterprise was in high school reading Halakhic Man. That wasn’t a high school assignment — my mom had been reading Soloveichik and gave me her copy and we read it together in some sense. And I remember being so transformed by the idea of Halakha as a lens and a framework through which the entire world can be refracted.

I really didn’t have the “baggage” that many people come to Halakha with as a rigid system of rules. For me, that was such an expansive and powerful picture and I now can see what are the ways in which that framework is problematic or harmful or reflects patriarchy.

What would be your message to people with this “baggage” attached to Halakha as a very rigid system and maybe someone who sees Halakha as in conflict with queerness and transness as things that are expansive and plural?

LS: I’m happy to offer an example from my own life. A few years ago when I was starting to make moves towards having top surgery in my life, I never asked the question, “can I have top surgery according to Judaism, yes or no?” That was not the question that I was asking because it was so obvious that the answer was yes. That’s not the point of Judaism — to ask the sort of existential questions of my life from a yes or no standpoint. Like can I exist? Yes or no. Is my body right? Yes or no. Are the things that I know about myself correct? Yes or no. That’s not the game.

What I was really interested in was how can I talk about this decision that I’m making using language that comes from who I am, using Halakha. So the question for me wasn’t how can I get permission to do this thing, and it wasn’t not a yes or no question because of Pikuach Nefesh (preserving life). It wasn’t a life/death situation for me, though I know that gender affirmation surgery can be a life/death situation for many people. I didn’t feel I couldn’t live without this, but I did feel like the most aligned, full, embodied way for me to live my life was for me to make this choice. So I spent a lot of time thinking about what are the frameworks that work for me? What are the ways of talking in our tradition? What are the principles, the concepts that are alive in this moment because of this experience that I’m having? That’swhat drove me to start finding ways to articulate my own experience as a trans person and supporting other folks in doing the same.

BS: What I might say to someone who comes to this project and has that experience of Halakha as a rigid system and is carrying a lot is: I see that. I want to hear about that experience and I want to name it with you and acknowledge it with you, and if we get to a place where we can have a conversation that is healing in some way, great. Our hope is that this project will be healing to folks in that situation — let’s learn together. Let’s dig in and see where we get and what the tradition can offer us from a place that’s affirming and embracing from a place that is about loving ourselves and creating a path for ourselves that is described in Jewish language, and let’s do that without the sense that it’s prescriptive.

LS: I think there’s a way that our community asks questions vis-a-vis trans folks and Halakha that we would call dysphoric questions or dysphoric halakha i.e. what are the ways in which trans people do not fit within the system, and how do we reconfigure and move and manipulate trans bodies such that they fit within this system that’s static. “Can a trans person ____?” is pretty much gonna be a dysphoric question.

We are trying to nurture euphoric questions and euphoric responses. We want a euphoric vision of Halakha, which is not about where trans people don’t fit, but about lifting up the new ways that Torah comes to life when witnessed through and experienced by trans people. One of the most amazing things to come out of this project, which so many SVARA-niks have taught me, is seeing the ways in which dysphoric questions can actually become euphoric when we are asking the questions for ourselves. To put it in concrete differently halakhic terms, when a cis person asks me where I go to the bathroom or how I figure out where to go to the bathroom, that’s a dysphoric question, a question rooted in dysphoria. When I’m around folks with a shared experience of gender to me and I say, “hey y’all what’s something that’s funny that you’ve done in navigating your way through public bathrooms?” and we can have a kiki about it. And we actually become powerful through that conversation.

We want a euphoric vision Halakha, which is not about where trans people don’t fit, but about lifting up the new ways that Torah comes to life when witnessed through and experienced by trans people.

Laynie Soloman

I love that framework of dysphoric vs. euphoric halakha. This conversation is exactly what I needed this week, I have to say. I’ve been having a bit of a chaotic week Judaism-wise and I’m just so grateful to listen to you both share your wisdom. This is more of a logistical question — what do you anticipate the form of the project being?

BS: Our intention is for this to be a communally oriented project. Which is to say that we intended to invite community participation in as many ways as possible both because we want to be in conversation with other trans Jews, that is a gift of this project for both of us and because there are limitations to who we are, right? Who we are both as transmasculine folks, as white folks, who we are as folks who have had certain amounts of access to Jewish learning spaces and have prioritized that access in lots of ways. We want to make sure we’re bringing in the fullness of our community. So what we have planned is we have a survey that’s out there and will close shortly. We have plans for some communal conversation where we share out our learnings from the survey and a series of writings sharing a little bit more about this framework of dysphoric and euphoric halakha, and actually about why buy into the Halakhic system at all.

Our hope is to address some of the questions that came up in the survey. Are there questions around surgery? Around hormones? Around being called up to Torah? Around just being in the world as a halakhic person? What is the right way to engage people who misgender us? That could be a really interesting question to take on from a halakhic perspective.

There’s one other piece, which is a collection of ritual written for and by trans folks, which in my mind is the most utilitarian part of all this. It serves to answer the questions that we and my colleagues and other religious leaders have asked, which is just: what do I do in this moment? What do I do? There’s a trans person who’s changing their name. How do I mark that? Well, one way is calling them to Torah and also being able to say, “here’s this ritual that our colleagues wrote that we can offer you.”

Is there anything that has come out of the survey that has surprised you?

LS: I would say I have been delightfully surprised by the number of folks who filled out the survey with a sense of newfound optimism about what engaging with halakha could look like. Tickled is not the right word — I’m giddy about that vibe. I feel so excited when folks who are ambivalent about halakha say “trans halakha sounds great!” That feels so joyous. It just feels so sweet.

BS: One thing I’ll share that surprised me is the survey asked folks about their gender identity and just the range of ways people are answering. Like when you get a survey and it’s like gender — sometimes it’s like male, female, other. Sometimes you get a good one and there’s genderqueer and nonbinary on there, but our survey just has a blank box. For an empty box, people are using their own language.

It’s great to see the breadth of gender creativity and the breadth of words that people are using to describe their gender. It’s just like yes, this is sweet — and this is the way the world should be. We should all get to have a box and as many words as we want to describe who we are in many ways, but especially in this particular way.

It’s great to see the breadth of gender creativity and the breadth of words that people are using to describe their gender. It’s just like yes, this is sweet — and this is the way the world should be.

Rabbi Becky Silverstein

You mentioned at the very beginning that this is a feminist project. Could you share a bit more about that approach?

BS: There are two things I want to be sure to lift up, in addition to the point about communal participation is like just because no one’s done the Trans Halakha Project yet doesn’t mean that this is the first time that trans people have thought about halakha or the first time that Jewish law has been confronted with questions of gender. So this project is situated firmly in a progression of feminist work, of trans folks who have looked at it and also ciswomen who have said “where do I find my place in this system?” who have opened up questions of their participation and therefore of our participation.

And I feel really grateful. Both to feminists who have engaged in halakhic stuff, but also folks like Judith Plaskow who wasn’t deeply engaged with the halakhic system, but really widened the framework of Judaism to challenge, in the biggest language, the patriarchy that is our tradition. I feel really proud on a big level to follow in that work. And then also on my own life level I feel proud to be able to say yeah, there are folks on whose shoulders I’m standing. Whether it was my rabbi growing up, Rabbi Karen Bender, who was one of the first out lesbian rabbis in the reform movement or our friend and teacher Maggid Jhos Singer or Rabbi Dev Noily who are just elders to me, who allow me to step into this work knowing that there are people who are supporting me.

LS: I think that part of what we’ve inherited is just the intellectual legacy of grappling with our tradition and not taking for granted that what does exist is what must exist or should exist or what always will exist. I think that the intellectual legacy of Jewish feminist thought is the linchpin of all of those conversations that I was exposed to in terms of thinking critically about Jewish tradition. I can’t imagine feeling the kind of permission I feel to interrogate and investigate and explore and transform our tradition without having read Judith Plaskow or Rachel Adler or Joy Ladin and all the many different sages who live among us, thank God, and who came before us.

I think that the intellectual legacy of Jewish feminist thought is the linchpin of all of those conversations that I was exposed to in terms of thinking critically about Jewish tradition.

Laynie Soloman

I think that gets to the idea of ancestry, which is central. It’s interesting to think about feeling disconnected from ancestry as in traditional halakha versus finding ways in and thinking about who you claim as your ancestors and how you move forward from there.

BS: That question has been particularly on my mind. Laynie, I hear you talking about reading halakhic man with your mom and I’m like if only. We all have varied and complex relationships with our parents, but both as a Jew and as someone who is working on being an activist or actively anti-racist to try and find the people whose work I’m relying on or who have set those examples for me has been really challenging — to have that sense of scope has helped me in feeling grounded in a historical lineage.

AF: I’m thinking about how to bring this project to different communities. Do you have a vision for how to do that?

BS: One thing that I feel grateful for in my own life is my professional opportunities to work in organizations like Keshet where the core of our work is reaching out to Jewish institutional communal life and saying queer and trans folks have a place here, and your community will be enriched by their presence. And our tradition will be enriched by their presence. And also getting to work and situate myself professionally in places like Svara where we say, you know what, this is actually for us.

What we’re doing is centrally for queer and trans Jews and other folks who are on a path toward liberation and whose liberation will bring liberation for all of us. And when I say that I mean folks with disabilities, I mean folks of a variety of races and ethnicities, I mean folks who are Jewish-adjacent, and folks from a variety of class backgrounds. Those are the people who we’re doing this work with and for.

I would love to hear any last wisdom you want to share. I am just so honored to soak in both of your Torah.

LS: I do think that one aspect of this work is making visible the way in which Halakha grapples with its relationship to insider/outsiderness and is in some ways an insider discourse. But the hope that I have is that the outside becomes the inside in some ways, which I think Becky just spoke to really powerfully. When you change who is the object of halakha into the subject, when you take people who have been objectified by halakha and then we give ourselves the permission to be the authors, that changes the game not only for the people who are now authoring the tradition but also what comes after it and after us.

The witnessing of that transformation from being an object to being an author or a subject transforms the conversation, transforms the possibilities, transforms who sees themselves as in the driver’s seat of this tradition. It’s a democratizing project fundamentally, but it’s not about erasing an inside or outside. It’s a transformation of that binary to begin with and really shifting into a new era of authorship, which I think is really needed. Not only for me and people with bodies that look like mine, but also for people whose lives and bodies are quite different from mine.

Laynie Soloman (they/them), Associate Rosh Yeshiva & Director of Transformative Leadership at Svara is a passionate teacher of Jewish text and thought, and they believe deeply in the power of Talmud study as a healing and liberatory spiritual practice. They love facilitating Jewish learning that uplifts the piously irreverent, queer, and subversive spirit of rabbinic text and theology. Laynie holds a M.A. in Jewish Education from The Jewish Theological Seminary, is a Schusterman Fellow (Cohort 5), and received the Covenant Foundation’s 2020 Pomegranate Prize for Emerging Jewish Educators. Laynie is an Ashkenazi third generation Philadelphian, and when they’re not learning Talmud, you can find Laynie reading about liberation theology, collecting comic books, and singing nigunim.

Rabbi Becky Silverstein (he/him) believes in the power of community, Torah, and silliness in transforming the world. He strives to build a Jewish community and world that encourages and allows everyone to express their full selves. Becky is a teacher of Torah, broadly defined. He is SVARA Fellow and a Schusterman Fellow. Becky currently chairs both the board of SVARA: A traditionally radical yeshiva and Jewish Studio Project.