Lower East Side Library: A Love Affair

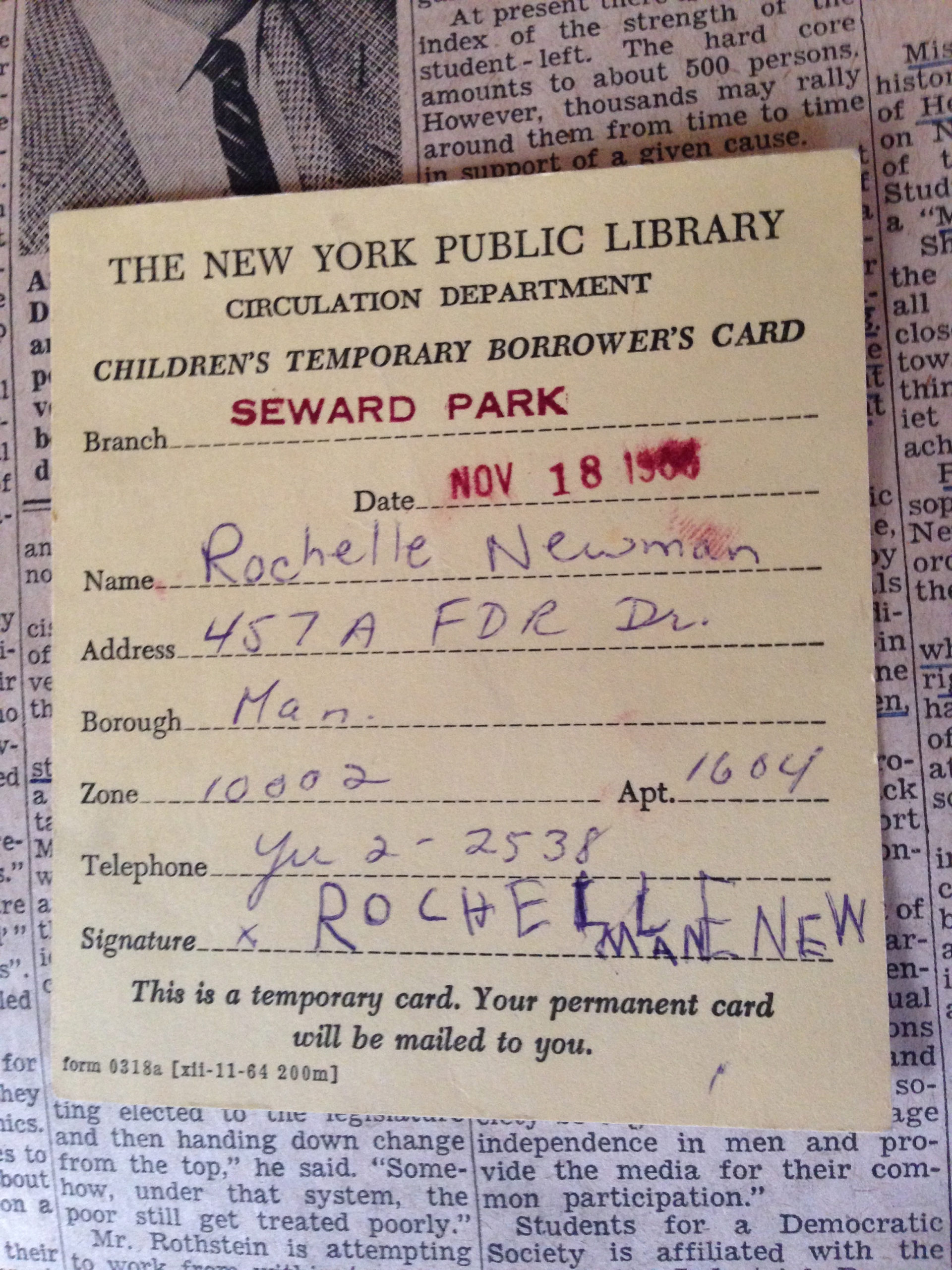

On November 18th, 1966, I got my first library card. I had just turned six. We lived on New York’s Lower East Side and our branch was the Seward Park Library. Built in 1909, the red and grey four-story brick building stood near the intersection of East Broadway, Essex Street and Canal. Unless it was raining or really cold, the Seward Park Library was an easy walk from our apartment on Grand Street off the FDR Drive. The Children’s Library was on the second floor. My parents followed me as I ran upstairs to the librarian’s station. When I had her undivided attention, I announced, “I’m getting my own library card.” She pulled out her stampers and a red ink pad and got to work. Then it was my turn. I concentrated on writing my name in big block letters. When I finished, I held the little yellow square card flat in my hands, careful not to bend the corners nor smudge the ink, the way I held my hamster babies when they were old enough to touch.

Like my first pets, the card was all mine. It also came with responsibility. At first, I was only allowed to take out two books at a time but, as I got a little older, the librarian trusted me with six. I agonized over which books came home and which books got left behind. How do you choose between Charlotte’s Web, Sounder, and The Phantom Tollbooth? I promised Harriet the Spy I would be back as soon as I had read and returned the others. I spent hours sitting on the floor of the Seward Park Library, or spread out at a table, oblivious to the shifts in light that came through the big picture windows as day became night. When it was time to leave, the librarian stamped cards she pulled from the pockets pasted inside of each book. I hugged the towering stack of stories to my chest as I walked carefully down the steep stone library steps and onto East Broadway. It’s likely my mother or father was with me but, when it came to reading, I was in a world of my own. As much as I loved the Lower East Side, I knew nothing greater than lying in my bed, reading by flashlight, and escaping for long stretches at a time.

In the sixties, my neighborhood experienced a cultural transformation, as did the rest of the country. New York City public schools were in heated debates about the pros and cons of integration and a host of related proposals, including racial balancing. Because of the Lower East Side’s ethnic diversity, integration was not an issue when it came to P.S. 110, the elementary school my brothers and I attended. Instead, as outlined in a 1963 School Board report, it was “the comparative size of different minority groups,” that was driving decisions on such things as busing and even the languages being taught. While going through my father’s clutter after his death, I found a file overflowing with pages of his handwritten and typed letters on the subject and newspaper articles with headlines like “School’s Racial Issues Called Public Matter” and “Schools In City Will Open Today Despite Boycott.” The articles, most from The New York Times, the New York World-Telegram and Sun, and the Village Voice, had been cut out and marked up. Select passages were underlined, circled, or asterisked in pen. They were often cited in his letters, serving to defend or destroy a given argument.

In a pre-Google, pre-Internet world, this type of cross-referenced critical analysis was no easy feat. The aforementioned 1963 document, formally titled District Proposal for Integration, laid out plans to address issues of disparity, most of which are unresolved to this day. One section stated:

The curriculum will be restudied on all levels. Greater emphasis will be placed on the job opportunities, diverse cultural groups in our city, and the role of the Negro and other immigrants in American history.

In English, there will be a new emphasis on books written by non-white authors, especially biographies and autobiographies. Books that include members of a minority in a real but favorable fashion will be selected for use. In the reading program, as rapidly as possible, we shall develop material which is real and will therefore be of natural interest for children of various ethnic origins living in a big city.

Some Sundays, my father and I went uptown to the Donnell Library, which faced the Museum of Modern Art. For a Lower East Sider, the subway ride uptown was a special treat. It was also intimidating, with a city-mouse/country-mouse feel to the experience. Things were shinier on 53rd Street; buildings were newer and taller, streets seemed cleaner, sounds and smells were subtler, and everyone looked much more magazine-like than anyone on Grand Street. Way downtown, we were all children of immigrants and we played a critical role in our parents’ American Dream. It didn’t look like uptown people had the same dream or, if they did, perhaps they were already living it. The children’s section in the Donnell library was like a supermarket, its shelves filled with a wide selection of everything. In comparison, Seward Park was more like a bodega, much smaller, a little messier, but the librarians knew you and what you liked. While I was impressed with the Donnell Library, I was never attached. Good thing too: it was torn down to build condos. Seward Park Library was recently granted historic landmark status and remains as vital

as ever.

There was a time when the Seward Park Library boasted the highest circulation of any branch in New York City. A 1913 New York Times article painted this picture of the library card-carrying immigrant:

“Centuries of famine and dearth of knowledge, and of cringing subservience to those who have had it, have taught the east side immigrant two important things about books: that what they contain can feed a starving mind and a hungering imagination with such royal richness as their lives could never afford them; and that their contents can lead him, step by step, along the journey to success and power and dominance. It is not far-fetched to say that many of the statesmen of the future are now in the making at Seward Park library.”

Here, Eastern European Jews gained access to the kind of literature and learning tools that both kept them connected to their culture and opened them up to all things American, including English language proficiency. With the Forward building just across the street, home to the world’s leading Yiddish newspaper, the library was often the meeting place of socialists and intellectuals, including Isaac Bashevis Singer and Leon Trotsky. The library was equally committed to serving the specific needs of the Chinese and Italian communities, with Chinatown and Little Italy only a few blocks away. By the ’60s, the focus shifted to the growing number of Puerto Ricans and African Americans. No stranger to bilingualism, the library quickly added Spanish language books and services, as it had done with Yiddish years prior.

Civil rights concerns were always part of the Lower East Side ethos. In 1909, the very first meeting of the National Negro Conference, now known as the NAACP, took place only a few blocks away from the Seward Park Library itself. The library’s history includes the work of two pioneering librarians, Pure Belpré, the first Puerto Rican to work for the New York Public Libraries, and writer Nella Larson Imes, the first black woman to graduate from the NYPL’s prestigious training school. Imes later took over the 135th Street Library’s children’s division and became a significant author and major figure in the Harlem Renaissance.

Along with a fifty-year-old library card, my files and piles are filled with evidence of my literary love affair that started at a very early age. I had crayoned my name and the words Books and Love on a ragged piece of paper torn from a composition book, the black and white marbled-cover kind. Further down the page, I had pecked out a story of sorts using my father’s Underwood typewriter. My little fingers must have pushed down as hard as they could on silver-circled keys, each with a letter on top. With each strike of a key, I triggered inky levers to rise up and move toward the roller, transporting a piece of the alphabet, punctuation, or a symbol. Sometimes the levers jammed together before they hit the paper and left their mark. My first line:

i read and i read i love to read books.

Notes from my father to my elementary school teachers support the sentiment expressed in this early work of non-fiction. On virtually every report card he signed, my father mentioned my passion. In second grade he wrote, “Rochelle reads continuously at home,” followed by “constantly,” the next year. By fourth grade it was “Rochelle is a voracious reader.”

In my 6th grade autograph book, I found another clue. Next to Favorite Author, I wrote Richard Wright. Looking back — all too aware that 1963’s goals of emphasizing diverse writers has yet to be met — I reflect on why Wright’s Native Son meant so much to me. I realize now that it spoke to a larger Lower East Side narrative about oppression, social justice, and fairness. These are the themes that so many of my favorite childhood books have in common — books as different as Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl and Dr. Seuss’s Yertle the Turtle.

Although the soundtrack to my Seward Park Library memories is all whispers and hushed tones, I have no question about its impact: the Seward Park Library, and the books I borrowed, amplified my worldview and my voice. I didn’t know it at the time, but with each book I borrowed, I kept so much, and was also entrusted with the responsibility of returning so much more.

Rochelle Newman, a writer who lives in L.A. and has specialized in marketing to U.S. Hispanic consumers, credits her Lower East Side roots with her love of culture, humor and language.

A version of this memoir appeared at the blog LunchTicket.org.