Idra Novey Talks Art, Appalachia, Antisemitism

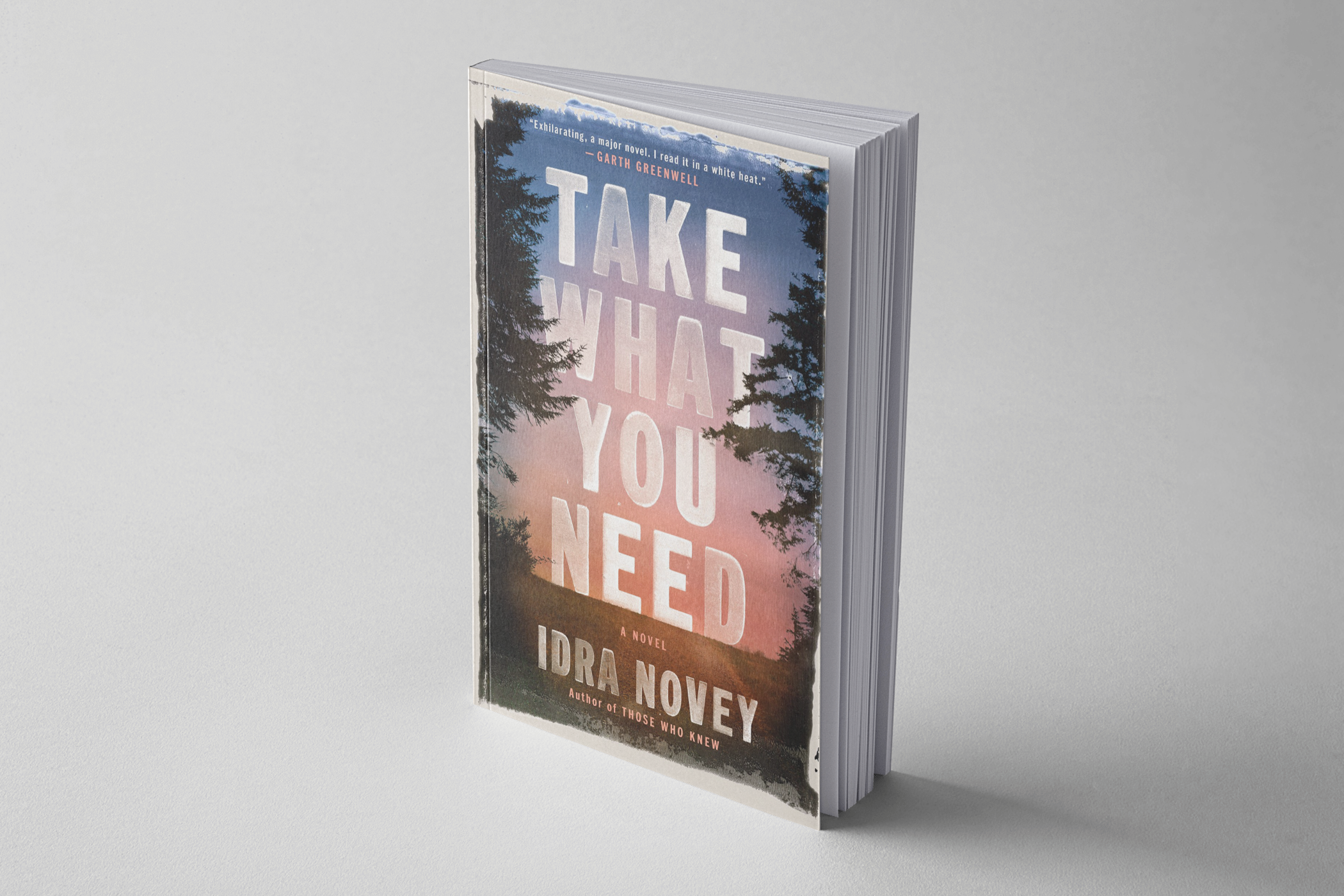

Novelist Idra Novey, whose latest book Take What You Need (Viking, $28.00) is the best reviewed book in the country this week according to BookMarks, talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the continuing mystery of the people we love most, and what can be built from what others have discarded.

YZM: What’s your connection to Appalachia? What has your experience been with that region?

IN: I grew up in Appalachia, as did my mother and her mother. Parts of my maternal family have been in the Allegheny Highlands of Appalachia for over century. My experience with the region is so complex it took me twenty years and ten other books of poetry, fiction, and translation before I could write this one.

YZM: The antisemitism in the book is subtle, yet chilling.

IN: The removal of graffitied swastikas from the door or wall of the synagogue was an ongoing task at the small synagogue in my hometown. In high school, I had several classmates who regularly used “Jew” as a verb. I don’t remember having any meaningful discussions about the normalization of bigotry, which was accepted as an ongoing, unfortunate aspect of life. What felt most emotionally true for my character Jean, in the novel, was for her to mention her father’s antisemitic comments but not to dwell on them. The taunts in childhood about her having horns is something she’s held onto, but quietly, privately. Those experiences end up in the well she draws from for her art.

YZM: The Jewish relatives that ran the junkyard a couple of generations earlier and who now manage it from afar seem to echo the history of many Jews who lived in Ohio river towns and small towns in other parts, where Jews were merchants in rural areas.

IN: My namesake, Ida Novey, started a scrapyard with my great grandfather Abe in 1906. They followed the patrilineal tradition of passing along the family business to one of their sons, who gave it to his son, my mother’s wonderful cousin Marty who runs it today, and lives in Baltimore.

I have no material connection to the Novey century in recycling but in college, when I published my first poem, I changed my last name to Novey, and I’ve published as Idra Novey now for two decades. I’ve wanted to do something artistically with scrap metal for a long time, which is why I started taking welding lessons with various metal artists, all of which contributed to this novel.

Jean gets her scrap metal from her cousin Marty, an homage to my mother’s cousin Marty. This novel provided a welcome occasion to research more about rural Jews, how many of them have a connection, as I do, to small riverfront scrap yards started at the turn of the century when Jews weren’t welcome in other industries.

YZM: The novel deals with the ways women have to struggle to be taken seriously as artists.

IN: While working on the novel, I immersed myself in the writing of women artists. Agnes Martin and Louise Bourgeois took on prominent roles in the book, but I also read all the writing I could find by Charlotte Solomon, Anne Truitt, Celia Paul, and Hilma af Klint, who were all repeatedly dismissed and written off, yet somehow still found the conviction to keep taking their art seriously. Writing about Jean’s nerve to keep getting on her ladder, stacking her Manglements as high as her room allowed, forced me to think about my own intrinsic motivation, why I’m so compelled to keep writing despite all the situations in which my books have been dismissed and written off as lesser in some way. When I finished this novel, I missed Jean’s company in my head. I found it a deeply joyful and rewarding process to imagine her continuing her sculptures after the gun blasts on her street at night, and despite her terrible anguish about being estranged from her daughter.