Bob Dylan, Viewed by a Gen-Z Fan

I can’t remember the last time I was as in love with anything as I am now with Bob Dylan. I have pretty much stopped listening to any of the music I used to listen to that wasn’t by Bob Dylan. I’ve discovered that I can listen to and read about Dylan for hours a day and never, ever get bored. His songs are so lyrically rich that every time I hear one, I seem to notice something new.

Forgive me if I seem to affirm the stereotypical image of a Bob Dylan fan as somebody extremely defensive in their belief that Dylan is a singular genius. In the time I’ve spent listening to his music, I’ve wondered about several questions. Is Dylan’s music anti-feminist? Would I be jamming this hard to it if, between the years of 1964 and 1968, he weren’t insanely hot? Would he be the same musician if he weren’t Jewish, if he had never been, if he had never had to stop being Robert Zimmerman? And the obvious: how can someone write like that? Sam Cooke wondered how a white boy could write “Blowin’ in the Wind”—my question is, how could a 20-year-old write it? How could a 21-year-old write “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall?” And how could that same person then go out and become a born-again Gentile?

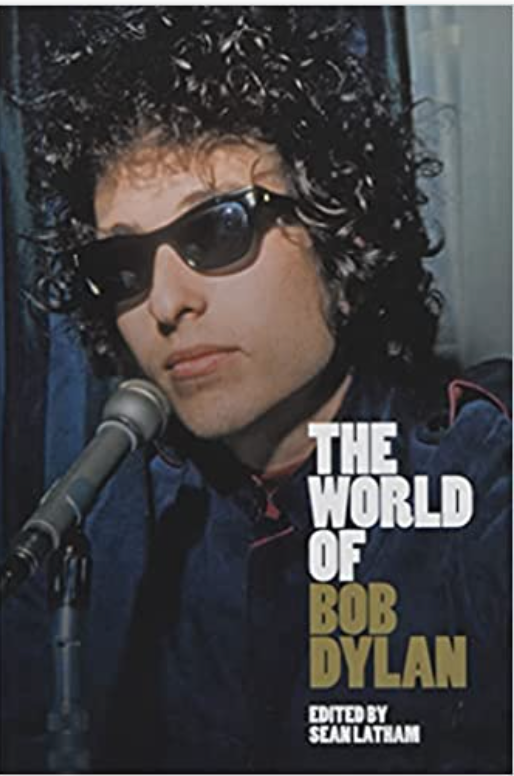

The World of Bob Dylan (Cambridge University Press, $25.95), a new book of essays written mostly by literature professors, insightfully addresses many of these questions, and to the extent that I previously believed in the singular-genius Dylan myth, it set me straight. Published to mark Dylan’s 80th birthday, the book contains mostly accessible essays that put his work in musical, cultural and political context, while also reckoning with his persona, his legacy and his brand. So while the writers are loyal fans, they know better than to think that someone could write songs like that in a vacuum.

Among his influences, the book shows, are American literature, world literature, the Bible, theater, Beat poetry and, obviously, folk music, including and especially African American folk music sung by Odetta and Lead Belly. As is common in the tradition of folk music, Dylan often adapts old lines and old tunes. “Blowin’ in the Wind,” for example, takes its melody from the African American spiritual “No More Auction Block.” That doesn’t necessarily make him a plagiarist (though he did lift parts of his Nobel Prize lecture from SparkNotes). As culture critic Kevin Dettmar writes in his essay here, “The name for literary theft, writ large, is writing.” No doubt, Dylan would leave his own mark on music with his genre-blending rock anthems of the mid-60s through mid-70s—but he couldn’t have done that without the influence of artists before him. “Much of Dylan’s music does not emerge mystically in the studio,” writes Sean Latham, editor of this collection, “but is instead the result of arduous work, deep research, and careful craftsmanship.”

Perhaps the best essay in the collection is the one on gender and sexuality. NPR music critic Ann Powers tracks Dylan’s physique and displays of masculinity through time, from the soft, cherubic folk-singer body he came to New York with that “can’t claim conventional masculinity,” to the cooler rock-star body he came into in the mid-60s, to—eventually—his current body, one that doesn’t have much time left.

Dylan has usually “[located] his erotic energy along with the rest of his power, within his role as a visionary,” Powers writes, but albums like “Blonde on Blonde” (1966), which includes “Just Like a Woman,” betray a struggle with masculinity. “The cruelty that runs up against the album’s frank seductions can be read, perhaps too generously, as a defensive move,” she writes, “against the women who threaten to overpower such a slender man, and against the softer man he once was and now fears to remain.” Regrettably, Powers’s essay is somehow the only one in the collection that calls Dylan’s harmonica a “detachable penis.” I am left to wonder how many Ann Powers-quality essays could have been written if this collection had included more perspectives from women and people of color.

Lauren Hakimi is a student at Hunter College, where she studies history and literature.