This Artist Never Knows What the End Will Look Like

Fiber artist Ayala Shimelman believes in “good accidents.” After all, it was after splattering cooking oil on her favorite dress in 1982 that she covered the stain with embroidery, beginning a 40-year calling.

What’s more, her day job as an occupational therapist led her to painter-musician-yoga instructor SiriOm Singh, her life partner since 1994, when she replaced him at a job.

The Tel Aviv-born Shimelman no longer works as a therapist, but she and Singh now run the Crosspollination Gallery in Lambertville, New Jersey, where both have ample space to display and sell their creations. A stone’s throw from New Hope, Pennsylvania–an early 20th- century artistic hub–Shimelman says that she appreciates Lambertville’s diversity and says that she and Singh have been warmly received.

Her work–including wall hangings and jewelry–has been exhibited throughout Lambertville and in places as varied as the Trenton City Museum, Beit Haomanim in Jerusalem, the Tel Aviv City Museum in the Park, and the Gallery at Mercer County City College.

Shimelman spoke to Eleanor J. Bader about her eclectic career in late October.

Eleanor J. Bader: You didn’t always want to be an artist, did you?

Ayala Shimelman: No. I have never been able to draw a straight line which I thought was a prerequisite for making art. Instead, growing up I thought I’d be a writer because I’d been making up stories since childhood. But there have been some good accidents in my life. I was cooking while wearing my best dress in 1982 and I got oil on it. This was before OxyClean–I thought that was it for the dress. Then a friend suggested I embroider something to cover the stain. I did, using a very basic stitch I’d learned in school. It came out nicely and I wore the dress for another 10 years!

Shortly after this repairing my dress, I moved to Jerusalem. I did not know anyone there but enrolled in an embroidery class. I thought it would be fun. The teacher opened my eyes beyond cross stitches and helped me understand that you can use a needle like a paintbrush.

After the three-month class ended, I worked with her in her studio for a few months and then took off on my own.

EJB: You were working an occupational therapist at the time.

AS: During the 1973 war in Israel, I volunteered in a hospital and saw occupational therapists working with people who’d sustained head injuries.

In 1982 I enrolled in a certificate program in occupational therapy at Tel Aviv University. This led to rewarding work with people who’d had strokes or traumatic brain injuries. I was part of a team and we did cutting-edge research and therapeutic work. I held a series of OT positions over the next seven years but when a new supervisor came on, things started to deteriorate. At one point, I told this supervisor I wanted to take an additional class. He said ‘no,’ and I cavalierly announced that if I couldn’t take this course, I was going to get my advanced Master’s degree in OT at New York University. I said it in anger, not really meaning it. Later, I decided to go for it. I had little to lose.

I applied to NYU but never heard back, so I had to come up with a new plan. I decided to open my own brain injury rehab clinic in northern Israel. But before I set the wheels in motion, I got a call from a woman who worked in the OT program at NYU and asked me when I was planning to arrive in New York since the semester was about to begin. We met, talked, and I decided to enroll.

EJB: Did you like NYU? How about living in New York?

AS: The first year was rough. New York City is not easy. My English was good but I was not fluent in the American way of being. The biggest difference was in the way OT was practiced. On one hand, OT practitioners have more clout in the US than they do in Israel, but the US healthcare system is terrible! At my employer’s insistence I had to work with patients I knew I couldn’t help, and stop seeing patients who had potential for great improvement because they did not have insurance.

When I completed the degree, I fully intended to return to Israel, but since I had not seen much of the country during the three years I’d been in New York, I opted for a job as a traveling OT, which was fairly common at the time. The work gave me a way to make money and see different parts of the country. One of my assignments was in New Jersey, This was 1994. SiriOm and I overlapped at this job for 10 days before he moved on. We stayed in frequent contact, fell in love, and got married in 1996.

EJB: You actually had left your art supplies in Israel, hadn’t you.

AS: Yes, but a few years after SiriOm and I got married, my life was more stable and my fingers started to itch, so I finally brought my art stuff to the US. In 2001 we joined an artists’ community in Trenton. Then we converted space in our home into studios.

EJB: Are you still working in OT or are you making art full-time?

AS: I stopped working in OT in January 2020 because I had a stroke. I had not intended to retire but the universe obviously had other plans for me.

In 2018, we opened our first gallery in Lambertville and we’ve since moved to a different location on a busy, commercial street and exhibit our constantly evolving work there.

EJB: Can you describe your creative process?

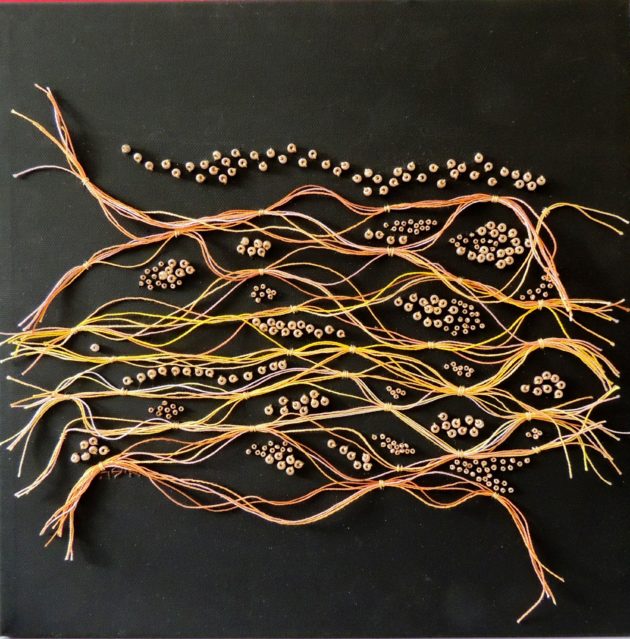

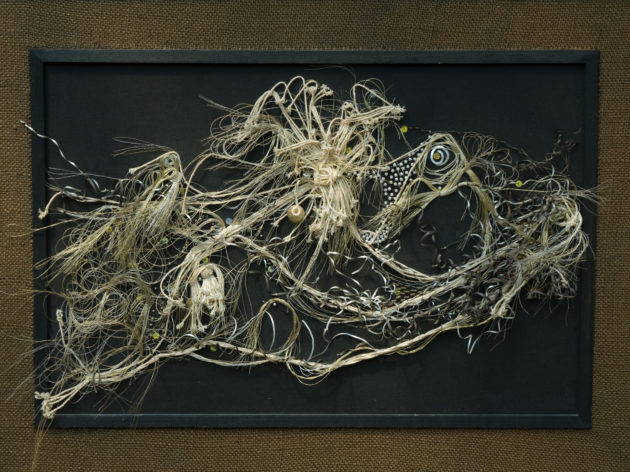

AS: I make wall hangings and wearable pieces like pendants, and also get commissions. Each work includes a variety of materials: Thread, fabric, metal shavings, hair, seaweed, and plastic pieces. When I start working,, I never know what the end result will look like. I don’t sketch my designs. To do so would feel like coloring by number, but a lot of recent work has depicted trees.

EJB: Have you recovered from the stroke?

AS: For a few months afterward, I could not do much of anything, but for most of the past year I’ve worked, but slowly. With time and therapy my right hand function has improved and I am now able to work a lot faster. My head is also a lot clearer so I can once again think about creating larger, three-dimensional pieces.