You Are Your Name

You are your name. In India, where I’m living for seven months as a Fulbright scholar researching the relevance of archaeological relics today, I’m constantly reminded of this.

“My daughter’s name is Zianna, it means bold and strong,” an acquaintance tells me.

“My name is Arushi, it means first ray of the sun,” says another new friend.

“My name is Pormishra, a god. It means, a god,” says a waiter.

“I am Suraj, the sun,” says another.

When I respond that my name is Elizabeth, Indians often say, “Oh, the queen. You are a queen.” Glad to dissuade them of any connection between my name and India’s former colonial rule, I tell people, “Actually, Elizabeth is a Hebrew name, it means house of God: beit means house; el means God.”

“So I am a god,” Pormishra says, joking, “and you are a god‘s house.”

In the US in 1965, the year of my birth, Elizabeth was the second most popular girl’s name. Growing up in predominantly Jewish areas of New York and New England, I was often one of many Elizabeths. In the school photo for my fifth-grade class at a public school on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, I am one of five. In the previous generation of my father’s family, the first names were even more explicitly Anglophilic: Stuart, my father, Carol, his cousin. When my father remarried into another Jewish family, we gained a Milton and a Byron. Ironically, though, the popularity of Queen Elizabeth and the other famous Liz of the time, Elizabeth Taylor, may have contributed to my name.

My father’s family was secular Jewish, and my mother converted from Catholicism as a native French speaker. She grew up in the US with a difficult-to-pronounce French name, and so she wanted me to have a name that people could recognize.

Yet, when I was 11, something happened that threw my Jewish pedigree into question. My

father and stepmother gave my new baby half-sister, the middle name Beth. In Ashkenazic

Jewish tradition—but not Jewish law—a baby is never named after someone living. Names of the living are considered off limits.

There is debate among the sources about the reason for this aversion to double naming, or what it means to violate it. But, it is generally agreed that if a baby is given the name of a living relative, as long as the name isn’t the Hebrew name or if either person has a different nickname or simply goes by a different name, it’s okay. Still, the precept that your name is who you are and that no one else can have your name until you die seems profoundly and closely linked to what it means to be Jewish. It is, after all, a tradition that values the word to the extent that, among the highly religious, even God’s name is never written or spoken.

Why this double naming happened in my family is still unclear to me, but growing up, I got

questioned about my family’s odd double naming often enough that I doubted the validity of my place in my Jewish family—or in Judaism at all.

I wondered: was I really a part of my Jewish family? Because my parents divorced when I was three, this question has followed me my entire life. It always brings me back to my name, with some mixed answers. Am I even Jewish?

After my parents divorced, my mother developed a pan religiosity, embracing Buddhism, Native American traditions, and aspects of her natal Catholicism and adopted Judaism. I celebrated Jewish holidays with my father and his second family, and my mother suggested that I should choose my own religion. I chose Judaism.

This was in part because my mother had remarried into a Protestant family. This marriage

lasted only two years, but her new husband, an anti-Semite, used that time to do what he could to erase my sister’s and my Jewish identities. He was hostile toward my Jewish father. While our then stepfather didn’t adopt us, he required that we use his last name. And, he insisted that my sister and I, age nine and seven, attend Sunday school at his church. He brought us there for Sunday services, though my mother herself refused to go.

When this marriage met its demise, my older sister, Jill, conspired to change our last name back our father’s, Jewish surname. She made this official one day when she brought me to register for my first new school after the second divorce, for fifth grade. The clerk handed us a form to fill out, and my sister, snatching it from me, wrote down KADETSKY. It could be said she gave me back my authentic self.

Is one’s Jewish identity proved by one’s name, one’s knowledge of tradition, one’s religious

practice, whether one—if she is a girl—had a bat mitzvah? Given my family’s secular and post-Orthodox stance on religion, the latter would have been unlikely for me regardless of the divorce. For some, knowledge of family recipes tells of a convincing enough link to bloodline.

Does a name prove your identity? In India, a name tells you not just who you are, but where you came from and the stories that connect you to that past.

As my mother suggested to me when I was young, in the US you can make up your own

traditions. Perhaps that extends to the significances built into your name. My stories about my name are, one might say, my own personal mythology. Perhaps a name is not so much who one is but what story one tells oneself about who one is.

Just as in India I can choose to be “Elizabeth: house of god” and not “Elizabeth: the colonial ruler,” my identity is in part which story I choose among several ambiguous options, which archaeological remnant I choose to bring to light. A single fragment tells only part of a story, belying the ambiguity embedded in its history. If my name is me, perhaps it can be equally a shorthand for questions raised and answers left complicated.

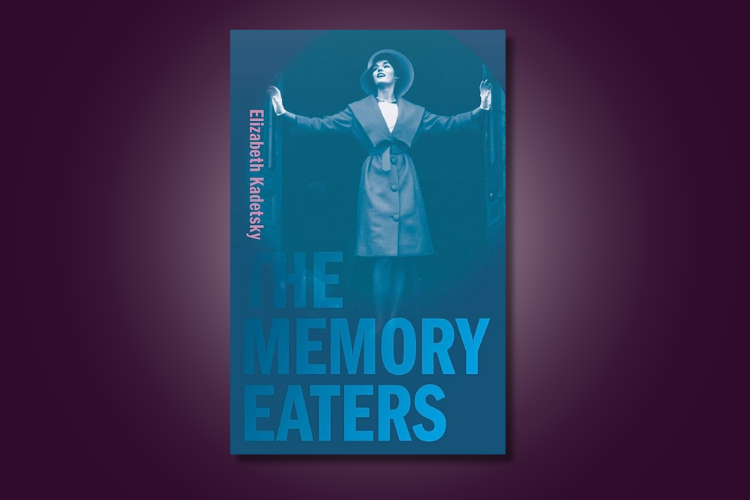

Elizabeth Kadetsky’s forthcoming memoir-in-essays, THE MEMORY EATERS (University of Massachusetts Press, March 31, 2020), explores family illness, addiction, inherited trauma, and the secrets of her inherited past.