In Defense of Lashon Hara

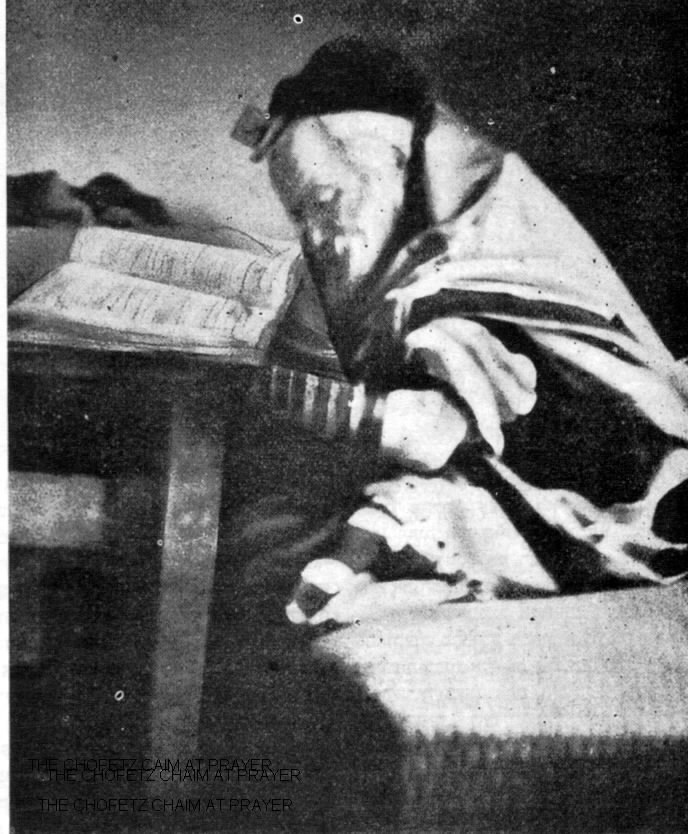

On my grandmother’s wall, a black-and-white photograph of an old, bearded man stares down at me. “Do you know who that is?” she asks.

“Yes, Grandma,” I sigh. She asks me this question every time I go to her apartment. “That’s our ancestor, the Chofetz Chaim.”

“A great tzadik,” a righteous man, she agrees. “He preached about the dangers of gossip, of lashon hara.”

In 1873, my great-great-great grandfather, Rabbi Yisroel Meir Kagan, wrote a book on the biblical laws prohibiting gossip and slander. The book was called Chofetz Chaim, “Seeker of Life,” and his followers started calling its author by the same name. When I first learned about the Chofetz Chaim, I thought his opposition to gossip made sense; after all, nobody likes to be talked about behind their back.

But growing up, I realized that in day-to-day life, people rarely characterize remarks made by men as gossip. And then I wondered, is gossip just a derogatory term for women’s speech? And are prohibitions against gossip just another way to silence women?

In the Chofetz Chaim’s Orthodox, Eastern European world, women did not study Talmud in Yeshiva; and they were excluded from political activity. So women talked about work, family, and the ins and outs of everyday life. In other words, when and where women could not talk about ideas, they talked about people: a topic of conversation that the rabbis termed gossip.

However, women didn’t and don’t just gossip when we lack access to highbrow intellectual conversations. We also engage in gossip in order to effectively combat injustice. We talk about people, rather than simply talking to them, because in a world of patriarchy and power imbalances, directly addressing those who harm us is often a futile or counterproductive strategy. Women, and all people in subaltern positions, gossip because we find strength in numbers.

On an individual level, gossip keeps us safe. When I was a sophomore in college, an acquaintance of mine saw me leave a party with a male classmate whom I had just met. That acquaintance texted a mutual friend that he was worried about me; the mutual friend, in turn, texted me, “I lived on the same freshman hall as Dave,[1] and a couple of women on our hall told me that he’s pretty bad about consent.” When I received her text, just before I got to Dave’s dorm, I told Dave that I was tired, turned around, and left.

I will never know for sure, but my friends’ and classmates’ gossip may have prevented me from being sexually assaulted that night. The women on Dave’s freshman hall likely never confronted him directly about his actions. Even if they did, perpetrators of sexual assault often respond by blaming the victim, so it’s not clear that confronting Dave would have changed his behaviors. These women likely never reported Dave to university administrators or police; after all, such authority figures often do not believe individuals who report sexual assault, and reporting a sexual assault rarely leads to consequences for the offender. Unsurprisingly, rape is the most under-reported crime in the United States.

But these women gossiped. They talked about what had happened to them and who the perpetrator had been. And because they gossiped, they helped protect not just their friends, but also women whom they did not know. At a time when a small number of serial offenders commit the vast majority of campus sexual assaults, such gossip helps students know whom to avoid.

Of course, I very much hope for a day when we do not need to rely on such gossip. Over the years, sexual assault prevention activists have made enormous strides in changing both policies and social norms in order to promote equity and reduce sexual violence. Yet in the meantime, gossip undeniably reduces harm.

Moreover, women do not just gossip in order to help each other avoid violent situations; we also gossip in order to effectively combat oppressive leaders and institutions. For instance, in 2010, the Shulamith School for Girls in Brooklyn suspended pay to eighty (mostly female) teachers and other employees for eight months. During this time, teachers lost their health care benefits and pensions, and many struggled to pay for rent, tuition, mortgage payments, and medical necessities. When the school neglected to pay back-wages, the teachers tried to resolve the issue by talking directly with the administration. Twenty-nine of the teachers joined a legal challenge that they kept out of the public eye.

After six years of private fights, when the school administration rejected a settlement agreement, the teachers realized that they could not convince the school to pay back their stolen wages through direct negotiations alone. So, in August 2016, they told their story to the press. A little over a month later, the school finally agreed to a settlement. The teachers reported that the school administration had responded to “the torrent of phone calls, complaints, and questions” it had received once the community learned about the teachers’ situation. In other words, by talking publicly—gossiping—about the administration’s wage theft, the teachers were able to mobilize the community on their behalf. And this community mobilization, in turn, pushed the school to finally treat their employees fairly.

Gossip is a powerful tool of resistance and of social change. Perhaps ironically, the Chofetz Chaim seems to recognize this fact. In his eponymous book, he writes that when Miriam gossiped about her brother Moses, God punished her for this act of subterfuge by giving her leprosy. He also explains that gossip among a group of people is even more dangerous than gossip between two individuals, and that “nurturing a quarrel” is more dangerous still. He cites “Korach and his congregation,” who rebelled against Moses, as an example of group gossip and quarreling gone awry. However, to frame Korach and his congregation more positively, they engaged in collective action to challenge Moses’s authoritarian leadership.

Just as God in the Torah punishes the gossipers and the rebels, people and institutions seeking to maintain their own authority in the present day often ban and stigmatize challenging speech. When the Shulamith School employees took their complaint to court, the school’s executive director berated them for spreading lashon hara about the school. Indeed, employers nationwide fire or threaten to fire their employees for comparing salaries, complaining about their jobs, and especially for talking about unionization. The Israeli government accuses Breaking the Silence and other human rights organizations of “airing [Israel’s] dirty laundry” in public and bars them from speaking at schools and military bases; and the US government harshly punishes whistleblowers who challenge our military and foreign policy.

These authority figures try to silence gossip because they know how powerful it can be. So it’s on us to fight back: to continue to talk about injustice, to build relationships with one another, to keep each other safe, and to organize together. It’s on us to defend each other’s rights to speak when those who speak out about injustice come under attack. We must keep “gossiping” in order to create a more just world.

Rachel Sandalow-Ash is a co-founder of and national organizer for Open Hillel, a movement of Jewish students and community members working to promote open discourse in the Jewish community on campus and beyond. She lives in Brooklyn.

2 comments on “In Defense of Lashon Hara”

Comments are closed.

I’m not Jewish. That said, you missed the point entirely.

Wonderful