“I Am No Victim”: Leah Lax on Living and Leaving Her Hasidic Life

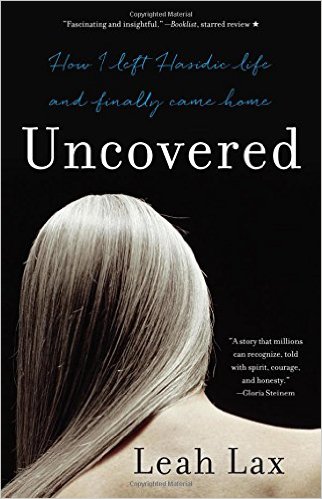

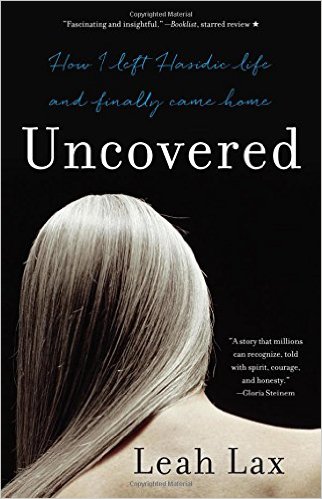

Leah Lax is familiar to Lilith readers for several of her essays in the magazine, most recently the economically told life history “One Woman’s Resume.” Raised in a Reform Jewish family in Dallas, close to her immigrant grandparents, who still ate schmaltz herring in their elegant nouveau-riche home; she says that growing up, she learned to crochet and ride a horse. In her teens she left this life—and her neglectful parents—to become a Lubavitcher Hasid, and soon after entered into an arranged marriage. Like the others in her community, she did not own a television, read secular books, surf the Net or go to movies or restaurants. Then after nearly 30 years—and seven children—she left that cloistered life behind. Her memoir, Uncovered: How I Left Hasidic Life and Finally Came Home, charts the years she gave over to strict observance of religious law, from hair covering to the order of putting on one’s shoe in the morning, from compulsive pre-Passover cleaning to relinquishing all questioning. It also reveals the secrets she harbored behind the observant façade, and the sprouting of a feminist consciousness as she came to know herself. She talks to fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about her life beneath the wig—and what it was like to emerge from it, uncovered, after so long.

Leah Lax is familiar to Lilith readers for several of her essays in the magazine, most recently the economically told life history “One Woman’s Resume.” Raised in a Reform Jewish family in Dallas, close to her immigrant grandparents, who still ate schmaltz herring in their elegant nouveau-riche home; she says that growing up, she learned to crochet and ride a horse. In her teens she left this life—and her neglectful parents—to become a Lubavitcher Hasid, and soon after entered into an arranged marriage. Like the others in her community, she did not own a television, read secular books, surf the Net or go to movies or restaurants. Then after nearly 30 years—and seven children—she left that cloistered life behind. Her memoir, Uncovered: How I Left Hasidic Life and Finally Came Home, charts the years she gave over to strict observance of religious law, from hair covering to the order of putting on one’s shoe in the morning, from compulsive pre-Passover cleaning to relinquishing all questioning. It also reveals the secrets she harbored behind the observant façade, and the sprouting of a feminist consciousness as she came to know herself. She talks to fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about her life beneath the wig—and what it was like to emerge from it, uncovered, after so long.

YZM: What drew you initially to Hasidic life?

LL: At first: their raw wordless melodies, the mysteries they said were hovering between the lines of our incredible texts, and the intimation that somehow this is me, too, since I was born a Jew, so that it seemed they were offering new self-discovery. I was 16—I think that alone explains a lot.

Then came Hasidic offers of the sublime, and assertions that they owned a huge Truth so old and vast it shut my small mouth, coupled with my weak will and my need to please.

If I dig, I always see more: the homoerotic quality of Hasidic life, and their promise that, if I followed the rules, I’d always feel I belonged, something I had always craved.

YZM: Was Hasidic life sustaining for a time?

LL: It was. I was barely 17 when I left my family, and received no subsequent financial support from them. Of course, I went straight to university on full scholarship and could have simply immersed myself there and grown up for a few years, but still, the Lubavitchers I had met gave me a sense of family, adult concern for my young life, structure, someone other than my damaged family to identify with, a place to go on weekends. They meant a lot.