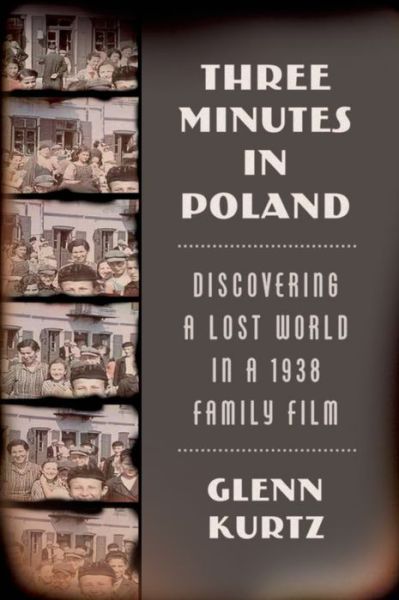

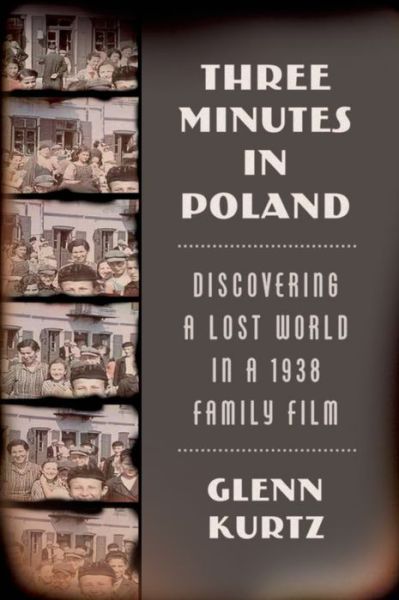

Three Minutes in Poland

When Glenn Kurtz happened upon an old family film in a closet of his parents’ home in Florida, he was intrigued. The film was shot by his grandfather, David Kurtz, during a trip he and his wife made to Europe in 1938—right on the eve of destruction. Kurtz’s initial interest grew into an almost spiritual quest, one in which he was determined to piece together as much as he could about the Polish town of Nasielsk—and the people who inhabited it. The result is the sweeping account in his book, Three Minutes in Poland, both a reverent attempt to document a lost history and a fervent desire to animate it once more. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough chatted with Kurtz by e-mail.

When Glenn Kurtz happened upon an old family film in a closet of his parents’ home in Florida, he was intrigued. The film was shot by his grandfather, David Kurtz, during a trip he and his wife made to Europe in 1938—right on the eve of destruction. Kurtz’s initial interest grew into an almost spiritual quest, one in which he was determined to piece together as much as he could about the Polish town of Nasielsk—and the people who inhabited it. The result is the sweeping account in his book, Three Minutes in Poland, both a reverent attempt to document a lost history and a fervent desire to animate it once more. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough chatted with Kurtz by e-mail.

YZM: How did you research this process of historical reconstruction?

GK: I worked on the book for more than 4 years, though in some sense, the research continues to this day. The images preserved in a photograph or in a film are preserved in a very peculiar way. They are both extraordinarily specific (individual people in a particular place at a specific moment), and at the same time utterly enigmatic. If you don’t already know what or who you’re looking at, the information in the image immediately becomes general, unspecific, and almost mythological (or in the case of old photos and films, nostalgic). Instead of seeing, say, “Chaim Nusen Zwajghaft, gravestone carver in Nasielsk in August 1938,” we see “prewar Polish Jews.” The general description is not inaccurate. But it does not convey information on the same scale as the image itself. It makes the image less specific.

When I first discovered my grandfather’s 1938 home movie, I knew almost nothing about it. I didn’t even know the town in Poland that appears in the film. The great difficulty, then, was to unlock the information contained within the images.