In Vegas That Year

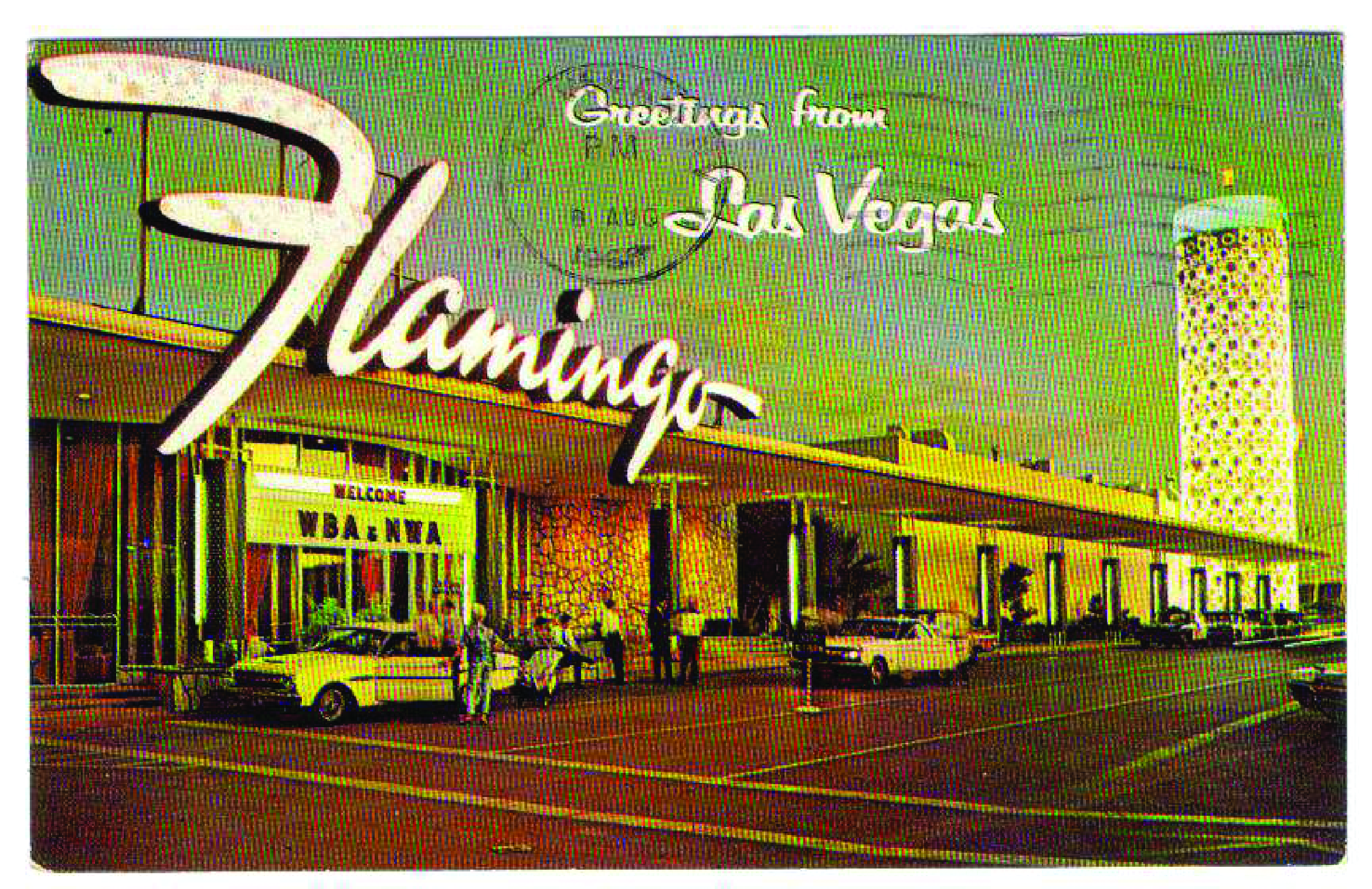

After the Flamingo lost $300,000 in its first two weeks, Meyer Lansky forced Ben to close and retool. Mr. Lansky sent some of his men from the El Cortez to poke through everything in the hotel before he himself flew out in March to review the account books, to check the cameras in the counting room, to re-rig the tables and rewire the slot machines. Out front there were to be no more thieving Greek dealers. No more tuxedoes. This wasn’t Paris or Havana. We needed to be friendly-looking, not intimidating. The new dealers would wear regular suits, just like the patrons. There would be bingo and giveaways, and just the idea of either one of those made Benny, his manager, wince. I knew Lansky wasn’t happy about Ben’s recent divorce. There was nothing at all, really, that Lansky was happy about on this visit.

After the Flamingo lost $300,000 in its first two weeks, Meyer Lansky forced Ben to close and retool. Mr. Lansky sent some of his men from the El Cortez to poke through everything in the hotel before he himself flew out in March to review the account books, to check the cameras in the counting room, to re-rig the tables and rewire the slot machines. Out front there were to be no more thieving Greek dealers. No more tuxedoes. This wasn’t Paris or Havana. We needed to be friendly-looking, not intimidating. The new dealers would wear regular suits, just like the patrons. There would be bingo and giveaways, and just the idea of either one of those made Benny, his manager, wince. I knew Lansky wasn’t happy about Ben’s recent divorce. There was nothing at all, really, that Lansky was happy about on this visit.

He and one of his men even made a point to watch the dress rehearsal of our new floor show. I’d been promoted from cigarette girl to dancing girl during the closure. When I’d told my father I wasn’t going back to school after Christmas, he hadn’t objected. Neither he nor my mother had finished high school, and the Flamingo was just too exciting.

And, anyway, who needed math and history lessons to be a dancer? I’d had more dance schooling than the rest, a bunch of local girls, pretty, but a little clunky. None of them could dance, not that we had much choreography to perform. Strutting, some waving of feather fans, a kick here and there, some tap. Our little numbers were scheduled between the real acts, a sip of water to cleanse the palate, the announcer introducing us with, “And now, from the Fabulous Flamingo Hotel, here’s our lovely line of dancers!”

I don’t think we lovely line of dancers were that important to the overall show, but still, I was nervous about making a good impression. We could be dumped just like the Greek dealers—and then what would I do? Sell cigarettes. Check hats. Or be sent back to school. So I was watching closely as Lansky, Benny, and a man I didn’t know sat on chairs in the empty nightclub, the three of them our only audience, their table the only one with a cloth over it, smoking and tipping their ashes into our flamingo-adorned ashtrays. The three kings.

It was the wrong time of day, of course, to see a nightclub floorshow. You needed night. The sun was bearing in on us despite the draperies, rendering the room vacant and dead, like any theater during the day. And having the men sitting there at the center front table with a tablecloth laid deferentially just for them made the rehearsal feel like an audition. None of the girls were wearing curlers like they usually did for four-o’clock rehearsal. No one was wearing practice clothes. We wore our pink-feathered costumes, our rubberized mesh tights pulled up high and rolled at the waist, our red high-heeled shoes. What if the men didn’t like what they saw? Would the costumes be taken from us? Would the opening be postponed still further?

Eventually, I would come to understand that our show, or any show here, had just one purpose, a purpose of paramount importance to Lansky and company, which is why they bothered spending any attention whatsoever on it and us, and that purpose was to send the exhilarated, titillated audience out into the casino eager to part with its money. Because the casino was the heart of Las Vegas, the whole point of the whole city. The baying patrons, flinging their money down, always amazed me. Didn’t they know the house always won, and the house would always win?

Benny, sitting there between Lansky and his friend, looked chastened, his normally ruddy, enthusiastic face a little empty, a little sandpapered, and he looked small, even though he was actually bigger than Lansky, who lacked Benny’s sartorial flair. Mr. Lansky wore a shirt without a tie and a herringbone sports coat, his hair combed straight back. He was not handsome, but ordinary looking, middle a little thick. He could have been a shopkeeper in Boyle Heights. Or a rabbi. The other man, whose name was Nate Shapiro––though I didn’t know this yet––wore a two-toned golf shirt and slacks. He was tall with a broad back and his hair was a black shock of a pompadour before there even was an Elvis Presley to sport one. Lansky might look to me like the rabbi at my grandfather’s synagogue, but the way he held himself, the way both those men held themselves, the way they smoked, the way they looked around the club said they were not obedient servants of the Breed Street shul, but men who considered themselves as powerful as the God to whom its worshippers prayed.

My father wore a bouncy enthusiasm, always looking for the next opportunity to grab, sure it was coming around the corner. Lansky and Shapiro had already grabbed hold of opportunity and had twisted it into something miraculous. They were more powerful, I realized, than Benny Siegel, but I hadn’t yet met anyone more powerful than Ben. I thought bigger than life meant powerful. But Lansky, and this Shapiro, lived smaller, they lived quietly, and there was nothing small or quiet about Ben, and for the first time, I realized that might be a liability. Quiet like my grandfather might be better, power hidden up the sleeve, not sprayed all over everybody in sight. I’d only ever seen grandstanding—in Ben, in my father, even in Louis B. Mayer with his big white semicircular desk up on a pedestal in his blindingly white office.

Under Lansky’s disapproving gaze, everything around me seemed wrong. Our costumes looked cheap. In this glare, my short pink dress had a tacky sheen to it and my red shoes were silly and the pink feathers ridiculous. I wasn’t sure the men would even understand that we were supposed to be flamingos, picking our way across the stage after the Andrews Sisters exited and before the Xavier Cugat band played again. Yes, I was finally going to have a chance to put my expensive dance lessons to some use, and I should have been thrilled, but our dour audience snuffed out any excitement. For me, anyway. The other girls, scooped up from dry goods store counters and restaurant cash registers in a pinch to fill the stage, seemed oblivious to anything but the fun of this. We’re flamingos! At the Flamingo! Ha, ha, ha.

I watched the Andrews Sisters sing “Near You,” watched the way they tapped their way toward the proscenium and back, swinging their arms in unison, doing a few step ball changes, singing their little songs, and I thought, This is boring. Even their costumes were boring, their hairstyles dated. Wartime entertainment. Patrons could get the Andrews Sisters back in Los Angeles or watch them in the movie houses. And they weren’t even that pretty, one of them with a big nose. Any extra on the MGM lot was prettier than the prettiest of the Andrews Sisters. This wasn’t what people would drive to postwar Las Vegas to see. The stark desert and the luxury hotels would need more riveting entertainment, more beauty. Not this. And not a handful of chorines like me doing some kicks and tap dancing between the real numbers.

Of course, this was 1947, pre Las Vegas showgirl, before the Copa girls and the Lido girls, before the sky-high headdresses and the sequins and beads. But I could see it all before it arrived—because I had already seen it in my mother’s Busby Berkeley films. That was what Las Vegas needed. Goddesses. Long rows of girls descending staircases, curving staircases like the one my mother stood on playing the violin in “Gold Diggers,” girls flying on trapezes, girls turning on spinning pedestals like the ballerinas in music boxes. I didn’t know that girls like that were already performing in Parisian nightclubs or in some of the clubs Meyer Lansky was opening in Havana, girls ornamented in every way with the exception of clothing. But I could sense that what we were doing was not going to fly here for long.

I looked to Benny. His face was blank, obedient. Whatever Meyer wanted to see on that stage was what Ben was going to put on that stage, no matter how he felt privately. He would watch the cheerful Andrew Sisters retreads. He would cut the paychecks for the twelve of us girls dancing chastely in pink. If Meyer wanted the clean American West, friendly, welcoming, bring us your money, we would present cheerful Americana as we scooped up the tokens and chips. I wrinkled up my face as I watched those Andrews Sisters dancing and singing.

There’s just one place for me, near you

It’s like heaven to be near you

Times when we’re apart

I can’t face my heart

They swayed their arms as if they had no idea their days were numbered and that pretty soon they’d be a nostalgia act.

I had cut my teeth on Hollywood, and on the Sunset Strip. Not on a desert backwater. So over to the side of the floor where we girls were corralled waiting for our turn to flip and flap, I quietly defied Mr. Lansky. To “Near You,” I stretched, threw my leg up, arched my back. I did a slow swirl that started in a crouch and then spiraled upward and ended with a head circle. I did the mincing steps of the high-heeled striptease artist, my arms thrown up to the heavens, hands wagging. By the window drapes where nobody could see me, I had my own private ball. And then, slowly, I became aware someone was watching me.

It wasn’t the crestfallen Benny, or Lansky, the man who’d deflated him. It was the man beside Lansky. Nate Shapiro. He wasn’t looking at the Andrews Sisters any more at all, just at me, only at me, and there was no censure in his face. Quite the opposite. He was smoking and watching me. I looked back at him for a moment and once I figured out that what I saw in his face was not disapproval, I continued dancing. I pretended I didn’t know he was watching, but I knew that he was. I felt myself tugging on a long fluid string to make his hands and legs and lips move and if I wanted to, I knew I could pull him toward me, though I was too naïve, of course, to have any idea what to do with him once I’d gotten him there.

When the Andrews sisters finished their number, I stopped, my back to the club floor, and I listened to the men clap. When I turned my head for a peek, I saw Benny and Lansky were applauding the Andrews Sisters, but not the third man. He was looking right at me, all approbation, and when I inclined my head in a small bow to acknowledge his pleasure in me, he smiled, eyes crinkling, all the former severity in his face banished and, suddenly, I liked him. All the men I knew on occasion used what I thought of as the bad face, the tough, unflinching stare meant to intimidate. The man had been wearing that face not ten minutes ago, but now his bad face was gone and he was looking at me as if he were delighted with me, this little girl he didn’t even know. And he was the one who tugged at that string between us, not me, tugged me to him with that smile. And then he leaned over to Benny, and I knew he had asked Ben who I was. And Benny brought him over.

Maybe it was because I was wearing this costume. Or maybe it was because I was finally grown up, which I’d been trying to do as fast as I could since we’d arrived in Vegas because there was nothing here for little girls and so many opportunities for young women. I didn’t know yet how these men were protective of little girls but predatory when it came to women. But you couldn’t stop growing up. The transition from girlhood to womanhood turned on a pivot. One day you were a child and then, all at once, you weren’t. Well, that day was my pivot.

The man had a pinkie ring on his left hand and a cigarette in his right, and he transferred the one to the other as he approached, and that’s how I knew he was going to touch me. I could see better now his Roman nose that counterbalanced all that hair. He was handsome, though not in a pretty-boy way like Benny. Still, he looked something like Ben, something like my father, some version of them. Without the intemperate rage. Without the failure. He moved with a tall, silky grace that actually reminded me of my old Hollywood dance teacher, Daddy Mack, who might have been short and fat, but when he moved all that weight on his two short legs, he wore his blubber like a mink coat. And that’s how this man moved, as if he were wearing a mink coat.

“E,” Benny said to me, not entirely happily. “This is Nate Shapiro.”

Nate offered his hand. I took it. It was large.

“I’m Esme Wells,” I told him, giving him my stage name, which was half my name and half my mother’s stage name.

Nate laughed.

He knew exactly who I was, Esme Silver, 15 years old, practically unschooled, a nobody, but he understood my affectation, even approved of it. All those men approved of ambition. Of reinvention. Naturally.

And we stood there, my hand in his while Benny frowned, probably because Nate was married, and not for the first time, not that marriage had ever inhibited Benny himself in any way in his various adventures, but because I was Benny’s Baby E and Nate was staring at me in this certain way and Ben could see what lay ahead, just as my father did, and he didn’t like it. He cleared his throat. He would have liked to clear the club, or rather, clear Nate from the club. But in the current pecking order, Ben didn’t have the power to do this. So the rest of the girls clumped back to the dressing room, where they would smoke cigarettes and drink Cokes, while I stood here. I can only imagine how I looked to Mr. Shapiro, a piece of candy in a candy-colored costume, my face orange with Pan Cake and my lashes an elongated black, my hair long as a child’s. The desert sun had turned my hair so blond it was almost white and the sun had darkened my skin. Was I too dark? Did Nate think I was a Negro?

I didn’t want to let go of Nate’s hand and he seemed not to want to let go of mine, either. What was happening was perfectly proper, an introduction, a handshake, but somehow it didn’t feel proper at all. And Benny, irritated, looked away.

My costume, though actually quite modest, suddenly seemed to feel riskily low cut and short, exposing too much of me. I flushed and Nate smiled at my transparency. Embarrassed as I was by my near nakedness, I nonetheless found myself in the grip of an absurd impulse to undress further, and all the while Nate Shapiro smiled at me. He’s an old man, I told myself. But the fact that he was older was exactly what I liked about him. He wasn’t striving to be something, he was already something. I had a feeling about him, the kind of feeling my father had when he knew his horse was going to come in win, place, or show.

But because I was underage, and because Nate was a careful man, more like Lansky the accountant than the id-driven Benny—who needn’t have worried about me, at least not yet, and by the time he should have been worried he was dead—it was therefore too early to know what would become of us.

And so all Nate said to me that day was, “Lovely to meet you, Miss Esme Wells.” His voice was a purr, with the slightest tinge of something foreign-sounding in it, which turned out to be just his flat Midwestern accent, though I was too ignorant to know it.

He was 50, and I wasn’t quite a third of that.

Adrienne Sharp is the author of the story collection White Swan, Black Swan, and the novels The Sleeping Beauty and The True Memoirs of Little K. Her novel-in-progress is “Survival City.”