Trauma’s Inexorable Trail Winds through Generations

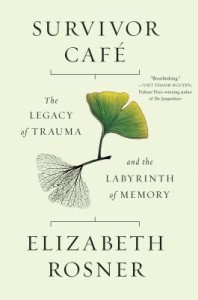

How do you write about the unspeakable? And how do you prevent it from slipping away into the darkness of amnesia and selective remembrance? In Survivor Café (Counterpoint, $26), Elizabeth Rosner emphasizes the importance of asking such questions.

How do you write about the unspeakable? And how do you prevent it from slipping away into the darkness of amnesia and selective remembrance? In Survivor Café (Counterpoint, $26), Elizabeth Rosner emphasizes the importance of asking such questions.

The daughter of Holocaust survivors, Rosner early on in the book discusses her trip back to Buchenwald with her father, and their attendance at a “survivor café,” an event where survivors, family members and sometimes locals gather together to share stories of their experiences.

From there, Rosner wends her way through stories and sources pulled from recent human rights tragedies. Though they are often difficult to read, each testimony is bound to the others by the way personal and generational memory is distorted, suppressed, and passed down.

The book addresses an often under-discussed aspect of trauma—its effects on later generations. Rosner writes of Marianne Hirsch’s term “post memory”—a phenomenon that implies inheritance can exist among family members as well as in whole societies—as well as recent research which reveals that trauma can literally change one’s genetic makeup. Despite the pain inherent in this realization, Rosner argues that the greatest danger lies in forgetting the stories entirely.

Survivor Café disrupts the narrative of forgetting, insisting on placing human faces, names, and stories onto skeletal and often incomprehensible facts. Stunning realizations slowly unwind the boundaries between traumatic events, intimately humanizing them. Rosner speaks to a woman whose father was a fighter pilot in World War II, who tells her, “My father may have dropped bombs on your father.” When a Holocaust survivor tells her story, Rosner is moved to tears by its similarities to her own mother’s life, a tale she was never able to discuss fully before her mother’s death.

This connection to stories has deep roots that stretch through generations. “I’m a woman who didn’t have children or grandchildren of her own,” she writes, “but instead chose to hold the stories themselves.”

Survivor Café is an exercise in mapmaking, in identifying convergent paths in apparently disparate legacies left by the world’s humanitarian disasters. There is a process Japanese artisans have developed called Kintsungi, in which cracked objects are repaired with gold or precious metals in order to emphasize the damage. Places where lynchings occurred are marked with small bronze plaques, printed with the victim’s name in gold. A new public school is being built at Sandy Hook. These acts of reconciliation are still incomplete, never sufficient, and yet Rosner argues that they are necessary, for “there is no complete truth that anyone can tell, and yet there is an obligation to keep reaching for the truth.”

The book dances with these inadequate reparations, often running into dead ends where words cannot be found. Some stories are untellable, while others can be told only in fragments or can be understood only through silence. Yet this is where the power of Rosner’s book lies: in the white spaces between the words, spaces that allow readers to reflect. She asks us to look inside ourselves, to learn from the past, to forgive, and to understand the deep connections binding us to our past, our future, and to all other things. “We are all obligated to remember, imperfectly and uncomfortably…because it’s the truth of being human, the monstrous and the divine,” she writes. “We are both lost and holy. We are neither. We own everything that happened to us and everything that happened to others before us. That includes holding guns and holding babies…and the mothers holding babies, watching. And the babies yet to be born, watching.”

Eden Arielle Gordon is a junior at Barnard College majoring in English with a concentration in creative writing, and she is a former Lilith intern.