Transitioning & Converting

“G-d damn it.”

I was 19 and on the phone with my then-partner. They didn’t want me to be a man. They were sure that I wasn’t one. They’d asked what else I’d been hiding. My desperate professions of love were met with a sighed, “You sure?”

Like a good girlfriend, I apologized for causing trouble, and the issue was tabled. Surely such a strong adverse reaction meant that I was wrong after all, right? I didn’t want to be a man, no. I just wanted what men had. I began to embrace what I believed to be womanhood — I had to make the best of what I was given, right? G-d made me just fine. I became a feminist. I embraced skirts and dresses, sex, manners, soft things. In spite of humoring my masculine personality, my partner continued to love the body that made me a woman. Our talks of the future involved my finished conversion, Jewish weddings, organic childrearing techniques I’d perused on the internet, hilarious accounts of how we would take oh so good care of the little Jew(s) swimming around inside a pregnant me. Judaism became more of a set of pillars and a roof rather than only a foundation. It surrounded us. It leaned me more towards choosing Ester or Tamar when my Hebrew name was in question — Ester for its resilience, Tamar for how it ended with –mar; a bite, a swift stab, the sharp r lingering like a fleck of meat in my teeth long after I’d finished the word.

Simchat Bat — the naming of a newborn girl

In 1992, I was born into a military family. It was cold and almost Easter, and along with being jokingly called Little Bear — my early arrival ensured that I’d retain the thick costume of black hair I’d grown in the womb — I was given a good Catholic name. Relatively uncommon. Vaguely Biblical. Radiating femininity.

Choosing a name for myself has been like trying to describe what my voice sounds like, or how water tastes. At least being named as a baby saves the majority of people the trouble. If I’d been correctly gendered at birth, I could have been the third in my grandfather’s name. Instead, my mother rallied for Samuel.

Bar Mitzvah — today I am a man

After cutting ties with my partner, I spent fall 2012 studying abroad, and, as the program ended that December, I returned to the States a man. That isn’t to say that the world made me a man: it was just that my journey “home” happened to be a decent jumping-off point to the rest of my life. I often call this point my honeymoon phase of coming out. I was happy and somewhat relieved that I’d finally found out a word to describe what I’d been feeling. I wasn’t a butch woman, a freak, a weirdo — I was a man in transition, and I was going to welcome myself. I set out to find a community. I couldn’t find much of one in person, so online was the next step.

At first, I didn’t give much thought to how all this played into my conversion to Judaism. I’d been enthusiastic about my conversion for my first two years of college, but once I started my transition, the conversion got put on the back burner. It wasn’t until late in my junior year of college that I started to consider my transition a factor in my conversion — and wonder if I had a place in Judaism after all.

Tefillin

Every morning, I put on a little garment called a binder that looks similar to Aladdin’s vest. It’s white, made of some silky Spandex-like material, and its front zipper occasionally shows through if my shirt is anything other than thick cotton. I ordered it from Thailand last summer; its exorbitant shipping fees and extensive wait seeming like small inconveniences compared to the wonders it does for my body. I zip the front, and the material pulls my chest down and flat, in order to mimic a biological

male’s chest. I wear this thing anywhere from twelve to sixteen hours a day; more if I’m out drinking and end up crashing on someone’s couch, occasionally having the presence of mind to reach under my shirt and unzip before my eyes close on their own. It’s not painful or annoying, necessarily — just a constant reminder that I’m not quite where I want to be.

Parshah B’reishit — in the beginning

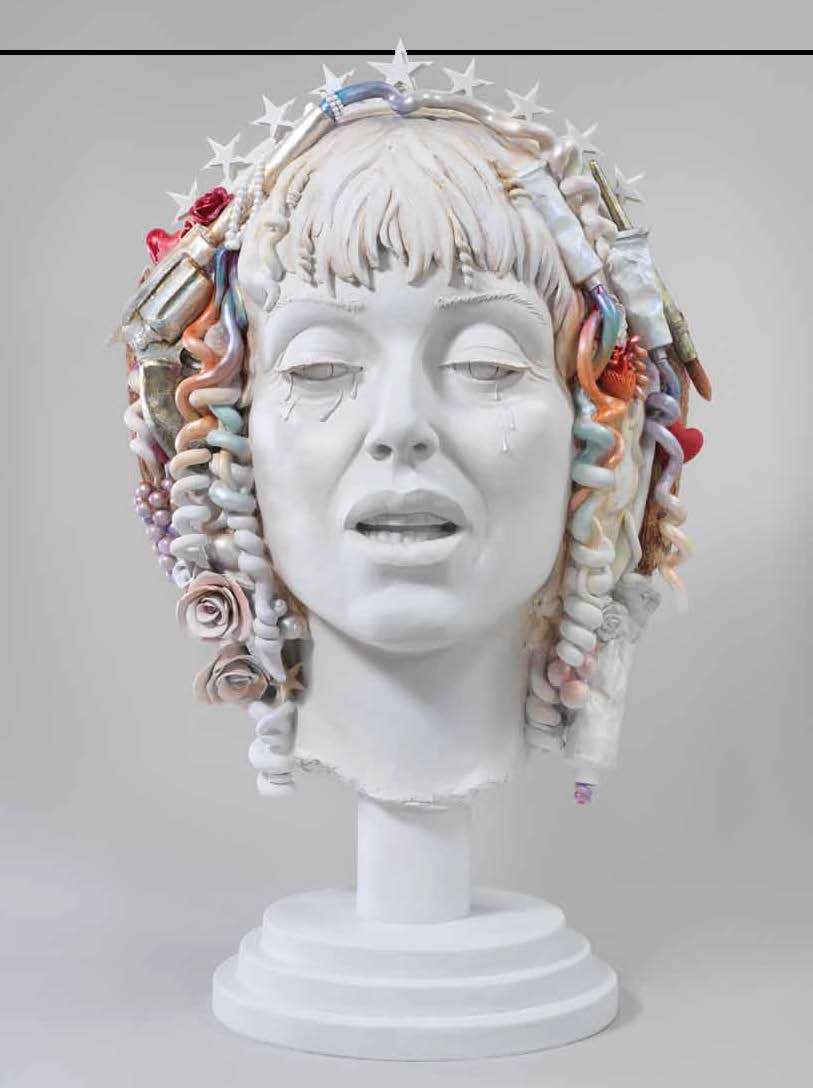

The part where G-d simultaneously instills hope and confusion in the transsexual Jewish community is the phrase male and female [G-d] created them. Perhaps G-d isn’t to blame, though, but the writers of the ancient words, who instilled in us a vision of the first human being, some man-woman hybrid that is only illustrated in my mind as grotesque and unrealistic. I constantly search for a sign that what I am doing is okay, and if I even “count,” since my conversion is still unfinished. This is the beauty of Judaism, I’ve found — answering the unanswerable in thousands of ways, constantly coming up both full and empty.

My solid, blind trust in Christianity had been fading since I was thirteen and being prepared for my Confirmation — the realization that my actions were fueled not by my own faith, but by others’. I spent my high school years performing informal research on other religions and sectors of Christianity. I wasn’t interested in a Messiah that had already arrived, I wasn’t willing to give up monotheism, I didn’t like having to go through a middle man to speak to G-d, I didn’t have the patience for Eastern religions, I didn’t agree with the requirements of Islam, and my hasty dabble in Paganism didn’t come close to comforting me as much as Judaism could. I couldn’t explain it. I still can’t.

The idea of being “not trans enough” is very much prevalent in the transgender community, or at least the online sector of it. Some people had been male all their lives; I’d only known for sure once I’d entered my early twenties. The accounts of trans men all compete for the same outcome: that they were always men, never women, and especially not girls. Unlike most other people in the world, they hadn’t allowed their gender expression to be regulated from such a young age.

When was I supposed to have started urinating exclusively standing up in order to have “always” been a man? Seven years old? Five? Was I supposed to have insisted on a gender-neutral nickname by the third grade or the fourth? How come I didn’t have the courage to get on hormone blockers before puberty wreaked its havoc on me? To continue allowing myself to be something I wasn’t — what was wrong with me? And heaven forbid I didn’t protest against wearing dresses or pigtails, or being seen as small or precious, even though I’d assumed that I had no other options — the fact is that growing up, I was what someone would definitely call a girl, a little one, and I would be lying if I said that I’m equal parts proud and ashamed of that fact.

I began to peel back my childhood for slivers of manliness. I needed roots, I needed some kind of grounding. Validation. Even though growing up I hadn’t quite been a boy on the outside, a little proof couldn’t hurt, could it? I helped myself to my mother’s photo albums: blue onesies, androgynous first and second birthdays, outdoor romps with my long hair tucked into my coat hood. I squirreled them away in some dresser drawer. I don’t know when I’ll need them.

The conclusion of Conservative Rabbi Mayer Rabinowitz’s paper “The Status of Transsexuals” rules that only individuals who have undergone complete sexual reassignment surgeries (complete, in this case, referring to the full medical assignment of genitals opposite of what was present at the time of birth) are seen as official members of their identified gender. This makes me wonder if I’m seen as some in-between being, some masculine woman poisoning herself with hormones before she has an extra 40 thousand dollars lying around to spend on what is consistently described in the text as “mutilation.”

At the heart of all this concern seems to be the question of whether or not a transsexual person can marry. Since I don’t see marriage in my future, I’m again left wondering if this even applies to me. I don’t like feeling so pervasively like the exception to the rule.

Pikuach Nefesh — who saves a single life has saved an entire world

Saving a world, I remind myself as I queue up a YouTube video on my phone and prepare for the disembodied male voice that will count me down from ten. One finger on the touch screen, another pinching a smidge of stomach fat. The countdown serves its purpose. Once the .15mL of testosterone cypionate is forced out of the tube and under my skin, I snap the needle from the syringe and deposit both into my sharps container. I lean back. If I fall asleep tonight without eating anything, I will wake up slightly nauseated, so I roll out of bed and plod to the kitchen for a snack before my eyes shut themselves. The next day or so will be occasionally punctuated with soreness in the injection site and an overall hungry feeling, but what I feel the most is a sort of electricity in me. Testosterone, well, gives me life. It assures me that I’m still doing something.

Shehecheyanu — who has given us life

I’m still working on the prayers I should be saying. Depending on what I read, I’m not allowed to say male mitzvoth yet. I’ve mastered the shehecheyanu, though. Aside from bits of the mourner’s kaddish, it’s the only verse that rolls off my tongue. Celebrating the fact that I’ve gotten this far is something I should probably be doing more often.

Hinei Ma Tov — how good it is for brothers to be together

“You’ve picked the wrong fraternity,” scoffed a Brother when I told him my intentions for joining. “We can’t teach you how to be a man. We’re all sensitive liberal arts majors.”

I pledged the fraternity in the fall of 2013 as a senior, having successfully made my interest known before the previous semester had finished. I’d anticipated a few hiccups concerning my involvement — after all, I hadn’t even gotten the gender marker on my driver’s license changed. The right Brothers must have reached out to the right higher-ups, however, and I received a formal invitation to rush that September. I was treated like any other recruit — I was assigned a “Big Brother,” given tasks to accomplish, called a pledge, called a man — and was initiated two months later as a full and deserving member of the fraternity. At our get-togethers, I did a lot of watching. I adopted a wider stance, I got used to roughhousing, I learned to offer my hand before opening my arms for a hug. When I reached out for help from my Brothers and received it, I knew I’d made the right choice. I’d gotten what I wanted: male role models. Affirmation of my gender. A support system when I ran into trouble on campus.

I was at some point informed that, unlike other fraternities, my Brotherhood’s values weren’t geared towards any particular faith. There were a few devout Christians in my chapter, if one looked hard enough, and I was more often than not lumped in with the three token Jews even though I wasn’t yet a real one. My Jewishness mostly manifested in my polite refusal of the hot dogs during the biannual cookouts with our sister sorority, and a couple Brothers turning Christmas or Easter into the generic “holiday” when asking if I’d had a good break.

All the men in my “family” — my Big Brother Novak and his three Little Brothers including myself — were all on different paths to G-d. Novak was raised Catholic, and worshipped only his music and the cosmos. Brigham never talked about the cross he kept on even in the shower. Thompson once wished us Jesus’s guidance as we started finals week.

In the transgender community, I’d be called a guy who wants “everything.” Testosterone therapy, a double mastectomy, name changed on all documents, a total hysterectomy, lower surgery. Ticking off all of the elements that could finally make me feel like my own almost seems like I’m a child making a birthday list. The difference here is that no one will hand me these gifts without at least a little bit of struggle.

At the time of this writing, I’ve been on testosterone for about eight months. That doesn’t stop me from wanting to feel more and more alive. The six grand in my savings will soon allow me to remove my shirt with confidence, but not my pants. I’ve stopped menstruating, but I still get “ma’amed” more often than I get “sir’d.” And what does this mean for guys who don’t want some or even all of what I want? Are genitals gender? I consider myself a man despite having little medical intervention at this time, that I’ve always been a man, that my mother’s Bible says before G-d formed me in the womb that G-d knew me, but I see myself in a larger realm of transition that will last for the rest of my life. It will be several years before I can afford all of the modifications I need, and in the meantime, finding peace with what I have is definitely easier said than done. I’ll bind these words as a sign. I’ll go forth on the road. Who knows where it will take me.