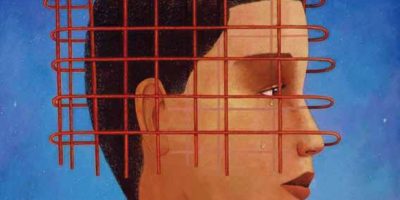

The Veil Unveiled

Why we cover - and reveal.

Humans have been concealing parts of their bodies ever since they realized they were naked. What is concealed and what revealed varies, however, and in The Veil (University of California, $21.95), Jennifer Heath collects feminist writing about coverings across cultures.

The veil has become a symbol of Islam in our century, and is both reviled and celebrated as such. Heath uses this symbol as a tantalizing opening, but broadens the scope of her inquiry, from the Indian sari and Hasidic wig to the hiding of servants in their quarters in South America. She includes such a range of activities under the veiling rubric that she threatens to blur her focus, which is on why and how we cover and reveal strategic parts of our bodies.

In the Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 2000 BCE), the woman who teaches the hero wisdom is veiled, and contributor Mohja Kahf believes that “to be veiled is to partake in a primal power: I see without being fully seen… like a queen… I declare this my sanctuary… from which I impart what will.” In a modern transposition, young working women in Cairo are adopting a veil and are “able to have the cake of modernity and eat the prestige of tradition too.” Some of their mothers are horrified, reminding their daughters that they fought for the right to unveil, which the daughters are now spurning.

Roxanne Kamayani Gupta contrasts the Muslim burqa with the Indian sari. She claims: “The sari attracts because it is a veil that covers but does not hide.” Moreover, in some Eastern traditions, all matter is a veil that covers the essence, the soul. It is women and goddesses who wear the sari, and it is the sari that transforms male into female and female into the divine. “All that cloth between body and world creates a boundary, a consciousness of the relationship between the inner subjective reality, our place of concealment, and the outer world of objective experience…”

Catholic nuns dressed in habits for centuries before Vatican II in the 1960s allowed them to think of dressing otherwise. Some “women religious” were overwhelmed by this change, fearing “loss of respect… loss of vocation, trouble with hair, vanity, expense, unsightliness of figure…” For these women, the habit was a uniform that gave them an identity and a status, and removed the need to be concerned with beauty and image.

Most of the essays in this collection interweave personal discussions with academic research. It is a promising approach, but it requires a high level of skill which isn’t always attained. I found the Jewish voices some of the oddest, particularly Michelle Auerbach (“Drawing the Line at Modesty: My Place in the Order of Things”) and Eve Grubin (“After Eden: The Veil as a Conduit to the Internal”) who write of journeying to the brink of Jewish religious observance, and then deciding to turn back. Although I could understand the themes of the hidden and revealed in these stories, their narratives were remote from the more central discussions in the volume about oppression and choice; veilings and equally forced unveilings; and the sexism and the feminism of the way we cover and uncover ourselves.

C. Devora (Viva) Hammer is a partner at the law firm Crowell & Morning and a research associate at the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute at Brandeis University.