The Song at the Sea

I think I throw up into the darkness, and I push because I can’t help it. My tichel, the sweaty black headscarf, slips over my eyes and I leave it so I won’t have to see. I want to cross my legs, sew my cervix shut and wait for sepsis to set in. Hardly anyone dies in childbirth anymore, but I can try.

I’ve had nightmares about this moment for months. In the nightmares—shit. The pain was nothing like this. “I can see the head!” Dr. Rosen, herself pregnant, almost six months.

“This isn’t his,” I gasp, but my voice is faint. This is Bill’s, this midwinter baby. I don’t want Stephen touching it, thinking it is his. In the darkness behind me, a voice counts the baby’s fingers and toes. The voice is Bill no it’s Stephen no it’s Bill. But then, Stephen’s calm breath above my forehead. “Here are your glasses.”

They are pushing something towards me. Stephen’s voice says, “I don’t know if she’s ready.” Like a good Jewish husband, he’s kept his eyes above the sheets, but it’s my face I don’t want him to see. Down there, I’m strong, but in my face, I’m vulnerable.

“Of course she’s ready.” It’s one of the nurses. There’s a tug between my legs—the doctor stitching me up. I don’t want to touch the flannel, but the nurse presses the bundle between my fingers and I have to open my eyes. “Here’s your boy.”

Will the eyes be brown, dumb cow-eyes like Stephen’s? But when I look, I’m staring directly into the clearest icy-blue depths I have ever seen. Winter eyes, and the baby doesn’t cry; just grimaces a little, squints at the snow-bright light. His face contorts and he looks just like Bill—I’m in bed again with Bill. I shudder. “Take it away,” I tell the nurse. Why isn’t he here with me? The nurse chuckles and hands the baby to Stephen. The weight is gone, but I still can’t breathe. “Lots of first-time mammas are too tired to snuggle.”

“This isn’t her first time,” Stephen says. “Just mine. She’s got two big ones at home.”

“Third time,” I say weakly from the delivery bed, but again, nobody notices. The anesthesia is wearing off and Dr. Rosen’s stitches are stabs now in my still-raw flesh. “This is our third child.” Mine and Bill’s: Why can’t Stephen see that?

Stephen rubs my head again. “Of course,” he says. “I still love Evan and Zoe, even now that I have one of my own.” I let Stephen rub my hair, like he does with his cat’s belly, watching television, but then he remembers we’re not supposed to touch. He snatches his hand away. “You did good,” he murmurs, blushing.

Out of the comer of my consciousness, the nurse returns, a lilac-scented blur. I barely open my eyes. The tichel has come untied but I can’t bring myself to care; it’s lost somewhere in the blankets that surround me. Nobody seems to notice that my hair is exposed. I wanted to do it right, with Stephen, but I feel like that fell away months ago, even before I lay with Bill.

Stephen takes the bundle from the nurse. I hear Stephen lift the baby up, up, almost to the light. “That’s him,” he says. “That’s my baby.” I drift away, and in dreams, I see Bill, hovering, demanding this baby he knows nothing about.

“It’s time,” Stephen said, almost a year ago. He wanted us to start making babies. He grinned the way he did whenever he thought about sex; embarrassed, but grateful. Fidgeting shyly with his yarmulke like in the pictures of him signing our marriage contract. Amazed I’d be willing to sleep with him. That I’d give him children, hearty Skolnick kids like his sisters-in-law kept popping out.

I have imagined a family portrait. Me in the middle, surrounded by bulging Skolnick foreheads, blunt Skolnick noses, and the endless drear of their mouth-breathing monosyllables. My own two children stand with me. Zoe’s delicate lake-blue eyes. And Evan, grinning from ear to ear, but probably plotting to take apart the photographer’s equipment. After I switched him to the Jewish school, he was speaking Hebrew inside of a month; the principal confided that he was probably the brightest kid she’d ever had.

When Zoe was born, my mother-in-law told me, “You two make beautiful babies.” Even then, the marriage wasn’t going well. My parents said it was punishment for marrying a goy. My mother-in-law didn’t see it that way, but even she didn’t know why her son wouldn’t touch us. “I just can’t deal with it,” he said, finally, when he left.

Dealing with it is Stephen’s specialty. Find a guy your kids like, the articles say. I saw how well he dealt with the detritus; I couldn’t pass him up. He could deal with snowsuits in the morning, keeping track of each of the kids’ little breakfast cereal routines. An excellent father, which was all I needed then.

Stephen asked me to go off the Pill, and he made love to me, gently, gently. “Your kids are beautiful,” he said. “I want to make more of them with you. I want our family to grow.” Stephen said all the right things, but I couldn’t bring myself to stop taking it. I didn’t want those big gap teeth like Stephen’s nephew Shmuli.

In May, Bill came to visit the kids. He phoned ahead to let me know and to schedule our coffee shop time. Usually, I’d spend our whole conversation steering him onto a neutral topic. But it was hard not to slip back into the pattern of joking and talking like nothing had happened. “We get along so well,” Bill would say. “It’s such a shame.”

The night he called, I finally went off the Pill. Stephen wanted to make love a few days later, but I said I was tired. Bill would have told me how hurt he was that I’d push him away, but Stephen doesn’t read meanings into things. He even rubbed my back until I fell asleep that night, and the night after, and didn’t say a word about his cock pressing into me.

They say things are iffy, fertility-wise, your first month off the Pill, but we’d conceived easily enough before. I imagined Stephen’s sperm: sluggish, easily tricked into flocking around a nonexistent ovum. Bill was different—his smart, aggressive sperm would persist; I never doubted they would find a way.

I wonder if Bill noticed anything unusual that time at Starbucks. “You know, there isn’t a day that goes past that I don’t think about you,” he said. “So many good memories.”

Normally, I would have changed the subject; this time, I let myself be drawn in. “Stephen wants children,” I blurted, then felt almost ashamed, taking his name in vain.

“You have children,” Bill said. “We have children; the best.”

“They are pretty special.” They were beautiful and brilliant, and I wanted more.

It was a short walk from Starbucks to where Bill was staying, at the Delta. In his room, he watched as I peeled off the layers from my hair. First the hat, wool with a brooch pinned in front. Then the tichel and beneath it, a hairband and ponytail to ensure no hair escaped. Only my husband was allowed to see it. I knew Bill wouldn’t ask why I would carry condoms, or even wonder if the brooch pin was sharp enough to pierce nearly-invisible holes in them all.

Amazing what bodies remember, flung back together like that. I closed my eyes the way I always had. Bill’s little cock made me feel almost empty inside, compared to Stephen, who fills me with happiness. Maybe Bill was my soul-mate, but I had no complaints with the body things Stephen gives me. I told myself I was with Bill for my children. This baby will look like Evan and Zoe; it will be their equal. I tell myself I’m doing everyone a favour. There are enough Skolnicks in the world already.

I knew Bill was very close. “Don’t you want to come?” he asked, noticing at last that I wasn’t moving around.

“It’s okay,” I said, and he came, then flopped back onto the bed. He didn’t comment when I slipped out of bed and went into the bathroom to change. Hat securely in place, I left the hotel with his semen inside of me. It’s mine, I thought, and alive.

At home, I said I wasn’t feeling well. “His visits always take a lot out of you, don’t they?” Stephen said. “Don’t worry; I’ll take the kids out for pizza.”

I lay down for the rest of the evening, visualizing Bill’s sperm, snapping and whipping within me. By the time he left town, I knew I was pregnant. I hoped Bill could sense it too, even from his great distance.

They have hauled me, like a corpse, into an almost-bare hospital room. The only colour comes from flowers in a vase on the dresser. Stephen and I are alone together for the first time since I went into labour. He talks awkwardly: my mother is looking after Evan and Zoe, everyone sends their love. So strange, this leisurely Friday afternoon; these are normally the most hectic hours of the week.

“What time is Shabbos?” I ask.

“Don’t worry; my mother sent food,” he says, and I relax again.

He’s propped up in a wooden rocking chair The bassinet is beside him; they keep them in the room now. Whenever the baby makes a noise, Stephen picks it up or pats it. I want to scream at him to stop. He glances over, notices my eyes are open. “What about a name?” he asks softly.

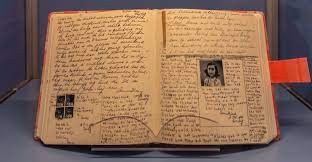

I shake my head. “No, no. It doesn’t need a name.” “I made a list,” he says. “Should I read it to you?” He pulls out his notebook, the same one he uses to make his lists: groceries for the cottage, packing to go to Ottawa, to Montreal. All the places Bill never took me. But right now, I don’t want any part of Stephen’s lists.

“Don’t,” I say, rolling away. But the bright light from the window hurts my eyes, and I have to roll back to look at him. I glance at the cart beside the bed and notice my hospital sandwich has arrived.

“My parents are asking,” he says.

“It’s my decision.”

“Yes,” he says slowly. This is the other thing about Stephen. He’s calm. “Did you think of any?”

“A few,” I lie. “Good names.”

“Great.”

“We’ll pick a name soon. I’m tired.”

“The bris isn’t for a week, but I need to talk it over with the Rav first. What am I going to say?”

I lean past him, even though I know he must be hungry, and grab the sandwich off the plate. Egg salad. I eat both halves right away, without stopping to wash my hands and make a bracha. I hadn’t realized how hungry I was. Stephen watches me patiently, making plans, no doubt, to go find out if they have mushroom-barley soup in the kosher cafeteria. He can wait.

I tell him, “Tell him, ‘It’s my wife’s baby.'”

There’s a little carton of milk on the tray, but I know it won’t be enough.

“I need milk,” I say. “I’m so thirsty.”

“Sure, no problem. We’ll decide tomorrow.”

“Decide what?”

The name.” He pauses. “Tomorrow, okay?”

“I’m too tired right now.”

He nods as if I’ve agreed.

“Of course; you rest. I’ll be right back with more milk. I might stop off in the cafeteria to see if they have soup.”

I dreamed about Bill the whole time I was pregnant, imagined him showing up, like the time he visited, while Stephen and I were still dating. We went up the CN Tower. We had one of those days where you just want to fall into bed with each other at the end of it. His hand at the small of my back made my thighs tingle intimately; I felt flushed whenever his hand rubbed against mine accidentally.

I went home at the end of that day, imagining the whole time that Bill would arrive at the door with flowers, toys for the kids, move back in so we could be a family again. Stephen was the only obstacle; him and his ponderous, old-fashioned religion. I called and told him it was over.

Two more days, Bill and I played hooky with the kids in daycare. I felt Stephen’s absence, and it was a relief Bill was lighter, less serious. On his last evening, after the kids were in bed. Bill called and asked if he could come over. My chest was warm and I shuddered. I wanted him.

On the phone, I could hear shouting in the background; he was calling from a pub downtown. The taste of his lithe little tongue against mine; that was all I wanted. His fingers on my feet, my wrists.

And then Zoe stood at my bedroom door. “Mommy?” She was crying.

“Just a second,” I told Bill. “What is it, Zoodles?” I called out into the hallway.

“I had an accident!” Zoe wailed.

“I’ll be there in a minute,” I said, picking up the phone. Bill was saying something, but I couldn’t make out what. “Bill?”

“Yeah?” he said, over the pub noise. “Sounds like you’re too busy tonight.”

“Wait—” I said. “Wait, it’s only Zoe.”

“Somebody here needs the phone,” he said, and he was gone. I didn’t even get a chance to slam the receiver down.

Zoe called to me from the hallway. “Mommy?”

“Just look after it,” I said.

“What? My bed is wet.”

“Sleep on the floor, then.”

Later that night, when I remembered her, I went and peeked in on Zoe, She was lying, curled up on the carpet, half on top of and half wrapped up in her swim-class towel.

I must have called Stephen sometime that evening, because he was there in the morning. He’s been there almost every morning, ever since. And even though I felt so weak in that moment, he acts now like I gained some mysterious power in that short time away.

Day and night blur in the hospital. I light electric Shabbos candles and they burn in the room long after the hallway lights are dimmed. Stephen wishes me a good Shabbos, but nurses clatter outside like it’s noon on a weekday.

Stephen tells stories from the weekly parsha, the Torah portion he’ll hear in synagogue in the morning. He says it’s a special Shabbos, but none of it has anything to do with me. Shabbos Shira— when the Jews sing Shira, the Song at the Sea, a gratitude-song for their redemption from Egypt. The story this week follows them, hiking through the desert towards Sinai, eating manna that falls each morning. It doesn’t fall on Shabbos, but some rebels sprinkle some on the ground on Shabbos, trying to prove that Moses’ teachings were false.

“In school, we’d make bird feeders for Shabbos Shira,” Stephen says. He wants me to ask why, but I can’t. I just stare at the pinkish curtains, not even wondering. “When they left manna on the ground and went to get the rest of the Jews to come and look, birds came along and ate up every crumb. So every year, we made bird-feeders, in gratitude for saving our faith.”

How could their faith have been so fragile after all those miracles? I want to ask, but I can’t. I suddenly need to get out of this room, away from Stephen and this baby. I’m too frozen to think in here. If Stephen knew what I’ve done, he might say that if I had been in Egypt, I wouldn’t have been redeemed.

The ones without faith, clinging to familiar Egyptian ways, those Jews perished in the Plague of Darkness. I shuddered when I read that in synagogue, imagining the frozen darkness closing in and strangling me.

“I need a shower,” I say out loud. Even though it’s Shabbos, I know there are exceptions.

The shower room is cold. I pull off the flimsy nightgown. The stitches between my legs sting and I’m scared that they will burst. There are no muscles left up there, it’s all numb, and when the hot water hits me in the shower stall, I break out in Goosebumps all over. Crouched down, adjusting the temperature, I start to sneeze. The muscles don’t resist and pee dribbles down my leg in pathetic bursts with every sneeze.

There is nothing left for me beyond the walls of this room. Bill is miles away. Stephen is eager to claim me and my children, but I don’t want any part of it, I’m covered in snot and womb-blood and piss, freezing and unwanted, so I stand there in the shower for the longest time, just trying to thaw.

After a few minutes, I hear Stephen’s voice. “Kath?”

“I’m okay,” I call out, though I’m starting to feel woozy from the steam. I soap around the least painful parts of my body before I shut off the water.

I don’t want to see Stephen, but he’s standing right beside the door.

“Thought you’d drowned,” he jokes when I emerge, holding out a scratchy hospital bathrobe like a butler. He’s not supposed to pass me things directly, not when I’m bleeding. Everything I had to learn seemed such a small price, before. Now, he drops the robe onto the floor for me to take.

I won’t pick it up; I turn and walk away. “Get away from me,” I say, striding towards the nursing station.

The nurse doesn’t notice I’m not smiling; she has news. “Perfect timing! He’s just waking up now.”

I lean over the counter to peer into the bassinet. The flannel is blocking his face, and I reach to push it aside. Another blur. A flash of black, and suddenly, I’m falling.

I’m on the floor, and doctors arc standing over me, three of them in green and white, with mildly concerned looks.

The youngest-looking doctor is grinning. “Beautiful kid you’ve got there, you might say he’s a knockout.” Nobody but Stephen laughs. I know I will die if I try to look at that beautiful baby again.

“I have to give the baby back to Bill,” I say out loud. “I don’t want this one.” But my voice has no substance.

Stephen leads my body, and my body goes along with him. I count the floor tiles as we walk. The nurse follows with the bassinet, and hands Stephen a bottle once I’m back on the bed. After she leaves, I stare at the corkboard, the flowers on the dresser beside the artificial candles. Everywhere except at Stephen and the baby.

“Hey,” announces Stephen. “He’s gone to sleep again. Guess he wasn’t hungry after all.”

Kath?” It’s Stephen, gently nudging me awake. ‘Honey?” Morning already. He’s let me sleep . through.

Dr. Rosen is here. Stephen leaves the room and I spread my legs open obediently. The way she’s bustling, I can tell this visit is purely routine: get in, get out. Usually I admire her style; efficient, too busy to pry. But now, I need to tell her— and the words just wouldn’t come out.

“Good Shabbos,” she says. I’d forgotten, she’s Jewish, too. Not like us; she probably came by car. “Heard you guys had some excitement last night.” She pulls on a glove and smears it with jelly.

Dr. Rosen shoves her fingers up deep inside of me, then out again, with a sucking noise that tugs at the stitches and stings. When she’s finished, she sits on the side of my bed. “Have you held the baby?” she asks,

“I can’t look at the baby,” I say.

She nods, shifting on the bed. Her stomach bulges, bigger than mine now, though mine is still swollen. “Is it really his?” I ask.

“It takes a while to bond,” she says, as if my motherhood is the issue. But I have witnesses; this baby came out of me. All Stephen has as evidence is a thrown away pill packet. “You probably don’t remember from last time; these feelings are completely normal.”

“Stephen doesn’t know anything.”

She probably thinks I mean he doesn’t understand about babies, because she nods. “He’ll learn.”

“I don’t want him around. This is my baby; just mine.”

“You’ve been through a lot,” she says. “But go easy on him.” She gets up from the bed as if she’s answered all my questions. I reach for her, but she goes across the room to wash her hands. “It’ll be good, don’t worry,” she says, throwing away the gloves and the little packet of jelly.

I want to tell her to wait, tell her everything that’s happened, but she’s already on her way out, saying she’ll be back tomorrow to discharge us, and wishing me a good Shabbos. I’m about to say her name, her first name, to make her really listen, but I can’t. I hear her out in the hallway, telling Stephen he can go back in now.

When Stephen comes back, he’s smiling. She probably said we’d be going home tomorrow. That wouldn’t have made Bill happy—he’d imagine all kinds of dire medical scenarios. Or wonder how stressful life would be with a new baby. But this is Stephen.

He’s obviously relieved to see me sitting up. “You do look better. I guess you needed your sleep.”

“When are you going to shul?” I ask. There’s an old synagogue a couple of blocks from the hospital.

“I’m back already. You were out like a light.”

Suddenly, the speaker beside my bed crackles. “Mrs. Skolnick?” It’s the nursing station. There’s a wailing noise in the background. “Your son is up; fixing to eat a horse. Are you nursing?”

I look at the full bottle from last night, unwanted on the dresser. Through all those months I never thought about this. I realize my breasts are sore, and wonder why Dr. Rosen didn’t check them or even ask if my milk had come in.

Stephen is looking at me, giving me the look I know means, “Whatever you want will be good.” Maybe I can believe him. The sun is just now starting to come up, peeking in around the blinds, and my feet, I realize, are warm at last under the covers.

I nod to Stephen. “Yes,” I tell the speaker. I’m not sure if she’s heard me, so I clear my throat. “Yes, I’m nursing: bring him in.” Another crackle, and the nurse is gone.

“Tell me again about the birds,” I tell Stephen.

As he speaks, I imagine what would have happened if the birds hadn’t come. Miracle after miracle, but seeing manna on the ground would send them over the edge. The effect of a miracle always wears off and when it does, we’re left in the cold, wondering if it ever really happened.

“Why didn’t the rebels die in Egypt?” I ask Stephen. “During the plague of darkness.”

He answers slowly. “One commentator says they were righteous then; they only stopped believing later” After the big miracles, when reality set in and they realized they could never go back. But how can Stephen understand, when he’s never not lived his odd, faithful Jewish life?

“You know,” he goes on, “some people say the reason we feed the birds on Shabbos Shira isn’t because of the manna at all. It’s because birds never stop singing Shira, even when the miracles are far away.” I suddenly need to go home; I want to make bird-feeders with Evan and Zoe. Even the baby; this new child, whose face I have barely glimpsed. I want to bring him home, but right now, I don’t even know what to call him.

“Do you have any names?” I ask.

Stephen leans over to bring out the notebook I know has never been far from reach.

I stop him. “Actually, I don’t think I’m ready.”

He frowns, just a little. Worried, perhaps, that I’ll never be ready.

“I don’t need to hear the list. Whatever you choose will be wonderful.”

“Really?”

“Well, I got to name the first two, right?” He nods. “This one’s yours; you pick a name.” Stephen’s glowing. Completely lit up from the inside. His eyes are wet and when the nurse comes to the door with the baby, a few tears leak down his face. He gets up and brings the bundle, wrapped in blue flannel now. over to me in the bed.

“Here’s mamma,” he tells the bundle. I peek in. and it’s a baby, red-faced from howling. Just a baby, I tell myself

“Quit that,” I say, nudging Stephen gently. “You’re getting him all wet.”

I take the baby, his innocent warm breath against my neck. His mouth gasps at the air, searching for my nipple. I offer it and he is content, snuffling against my skin. My milk descends like dew, drop by drop, draining like healing tears from the centre of my soul. His eyes are wide now, and I can just make out the tiniest flecks of brown there, a soft rich loam like the earth itself, trapped too long beneath the frost.

Jennifer M. Paquette lives with her two children in Toronto, where she is a regular contributor to the Canadian Jewish News. Her articles have been featured on national radio in Canada and the U.S., and her stories appear in periodicals and anthologies.