The Portrait: Algeria 1919

She, Etamine, leaves no mark as she moves through the medina’s narrow streets that lead to the new town the French have built. No one has to cry, Baleck, baleck, Out of the way. She clings to the walls, never minding the water that puddles there or the pockets of dog piss. She’ll return home in the same state she has left — clean, without dust on her shoes. Even her shadow on the whitewashed walls surprises her.

She knows she should have died on the day she was born, and her real mother should have survived instead. There were so many children already inhabiting their two rooms. A mother was needed to raise those children. A house without a mother is death, Etamine thinks. Slight, with her pale hair and eyes, she was the one responsible for that death. Within hours, Etamine was living with her oldest sister, Sadia, in the rooms above the grocery owned by her husband Jacques. There, the family pretended that Sadia was her mother, Jacques her father, and their son, Maurice, her brother. In the early days, Sadia nursed her sister along with Maurice, who was only days older. The milk forever tasted sour to Etamine, even accusing. Still as Etamine grew, she called her sister — Maman, and Jacques — Papa. But alone, she always thought, Sadia, my sister, who must hate me because I killed our mother, who should have lived instead.

Etamine was born in blood, and it has washed away her outline, so she leaves no footprints when she walks, makes no noise when she sleeps. She, Etamine, is air that doesn’t move, a dream that no one should have invented.

Because she is only air, Etamine has the vision. She can easily slip between the thoughts of women and discover what they are feeling before they sense it themselves. She understands why their hearts race in the street. How they lust before night falls. Men are a mystery to her, for their minds are blocked with a hard barrier, stronger than mountains that rise around Sétif.

But women she knows, as she knew her own mother before her birth. Has found her mother’s fatigue and the angry hands that pushed against the belly holding Etamine — Not another child. Sometimes she believes those hands wanted her to die — expelled in a mass of blood vessels with an unformed, pulsing heart. But that vision grows more distant as the newer ones take its place, sometimes filling her head with so many women’s voices that Etamine thinks she will grow deaf.

When she was only three, she found Sadia’s thoughts tucked into her small bed. Under Maurice’s bed, Sadia placed love and hope. But in Etamine’s bed, Sadia deposited only anger and guilt. A resentment that sprung from an ever-flowing, wild river.

Even on the days just before the Sabbath or Passover, when Sadia furiously cleans the house, Etamine senses the anger. Not only for her, she realizes, but for everyone and everything except Maurice. It settles on the chairs, peers from the cabinets, hovers around the mezuzah at the door, and slides along the floors that her sister scrubbed. It descends to the grocery. And there, Etamine, finds its source.

Jacques is much older than her sister. It isn’t only his white hair and his knobby hands or the blue veins along his nose and across his legs. She can’t listen to his thoughts, but knows his fatigue.

“You only have two children, Jacques,” Etamine hears her sister whisper at night. “Show more interest in them.”

“I love the children,” Jacques replies. “Remember I wanted more.”

“Ah,” Sadia hisses, “how you hold that against me. I didn’t want to lose five infants.”

“God’s will,” Jacques murmurs.

“The work of the djinn. And you still demanding to fill my womb, even when you know I can’t carry them.”

“I only wanted to love you the way I knew how.”

“This marriage was your idea. You found me and took me from my parents.”

“Sadia,” Jacques asks before he turns to sleep, “will you never be content?”

Some nights Etamine leaves her bed to study them as they sleep. Even when she was just ten, she already understood a lot about the love between men and women. For a long time now, she can detect the eggs that descend into the wombs of women, and wait there for the part of men they need to make them whole. She feels the wash of menstrual fluids that fill their quarter each month, and the disappointment of women in the hammam who wish for children.

At her parents’ bed she finds another presence that reaches out to her. On all the nights that Etamine watches, the spirit of Jacques’ long dead, first wife rests alongside him. Sometimes the spirit wraps herself between Jacques’ arms and legs, almost disappearing into his very flesh.

Is it the djinn? Etamine wonders. The evil spirit that Sadia worries about every day?

On another night, the dead wife turns toward her, studying the girl who should have died. Etamine grows warm when the spirit swirls around, piercing her flesh with small pricks of understanding. She breathes in and out, taking in the spirit with each inhalation, filling herself with another time.

She sees then. Jacques when he was young, with black hair and a full black beard. With brilliant blue eyes so unlike the watery, yellowed ones he views the world with now. With strong limbs and a straight back. And with dark hair covering his chest and descending to the maleness that stood as if at attention like she’d seen the French soldiers straighten their backs before their lieutenant.

Sitting before Jacques so long ago was that first wife. Her copper hair rolled in waves down her back as she held him to her and wrapped her limbs around his hips, until her belly grew hugely white. Etamine can feel the child living beneath the skin. Then the woman’s legs are wide open, and Etamine knows that this is a birth like her own, and that someone is to die. But when she sees Jacques bend over the limp baby and the dead woman, she understands.

Even years later Jacques has willed his lost wife to remain. And she spends each night between Jacques and Sadia, so that they would never truly be together. Etamine, too, wishes the spirit to remain — warming the house where there had been only cold.

“Come with me today, Etamine.” Sadia is preparing for a trip to the hills that surround Sétif. “We need to collect plants before the cold comes,” her sister insists.

At home Sadia speaks little to Etamine. But on the hills she always explains which plants are important and why. How to use the seeds or the twigs or the dried leaves. Which to pick in the spring, which in the fall. How to fix broken bones, minimize the asthma, calm insect bites. Which feed the body, which cure diabetes, or stop bleeding, or cut the pain of childbirth. And which plants increase the function of the liver and build up the red blood cells so necessary for life.

“You must wrap the plants carefully,” her sister explains. “Be careful not to disturb the part that is the medicine. “ Etamine watches her sister carefully pluck the plants. “Then we cover everything with brown paper to keep it safe.” She folds the plants in the paper Jacques uses to wrap groceries in the store.

Etamine writes quickly in a small book she carries for those moments as Sadia explains.

“Draw this flower in your book,” Sadia says, “so you won’t forget.”

Etamine sketches the plant, how it sits in the earth, how the leaves are shaped, and the size and color of the flowers.

“You will be a healer like me,” Sadia adds.

These are the times when Etamine is truly happy. When she’s preparing the plants next to her sister, and when she waits for the bread to bake in the community oven. Below street level, lingering near the ovens, Etamine feels as solid as the loaves. She loves the rhythm of the men who take the unbaked bread and shove it into the oven with wooden paddles, then retrieve the already baked in one movement like a dance. She carries the bread home, still warm and fragrant.

And she is happy in the steamy hammam with the other women, where she rests with her back against the marble wall, just next to the jets that breathe out eucalyptus-scented steam. She loves to watch the steam filled with women’s sighs and laughter rise to the ocular openings in the domed ceiling.

Every woman knows that magic of another kind happens in the hammam — mothers are searching for wives for their sons. While they chat, they measure the qualities of the families and the size of daughters’ hips. Who is wide enough to give birth easily to many sons? Who has breasts perfect both for pleasure and suckling? In the hammam even nipples become a commodity.

Occasionally, Etamine watches Sadia engage in one of those conversations. The mother of some boy looks at her as she hugs the wall.

“This is my daughter,” Sadia will start. “She reads French and Arabic. She helps in my husband’s grocery, and her almond cakes are even better than the ones in the French pâtisserie. And,” her sister adds solemnly, “She will bleed on her wedding night,” Sadia promises with a smile. In the world of unions, an intact hymen is as important as wide hips.

Despite the warnings, some girls have forgotten the cautions against carnal knowledge before marriage. Etamine can find them in the hammam — the girls who throw away their virginity. She encounters their freedom and wishes it for herself.

Not that she dreams of becoming some man’s wife. Maybe, she thinks, maybe I just want to disappear into the medina. There she could heal all the ones who need her. There would be no marriage bargaining, no stained sheets on her wedding night. She, who should have died, can spend her life chasing death from the homes of the sick.

Etamine knows she’s not allowed to walk the streets of the medina alone. It’s Maurice’s job to follow her to the bakery. Although he’d rather run off and sketch the world he’s discovered outside the city, he still has to protect her from whatever danger threatens a virgin of marriageable age. Even now, after she’s sixteen and too old for school.

Finally, one day, Maurice disappears. He’s left a note for his parents — declaring his desire to be an artist. Sadia rages with worry. Jacques ignores her and descends to the grocery. “He’ll come home tonight,” she tells her sister after three days. She senses Maurice is on his way home even before he appears in the street.

“Can you be sure?” Sadia asks, her eyes softening.

“I promise.”

“I thought it was the Eye,” Sadia goes on, “furious that I had stolen so many back from death. My son for the debt.” She kneads the bread into its final shape.

“Not this time,” Etamine says. “Not with Maurice.”

Then this will be the last morning that she can walk alone. She feels a sudden bravery that pushes her to leave the bakery and wander the streets she’s always avoided. Even the bakers are surprised to see that she doesn’t take her usual place by the oven. They’ve grown used to me — like the cat that always wanders underfoot.

She follows the streets that lead to the French part of the city. She wants to visit the wide boulevards planted with flowers. To pause when she desires, drink when she needs, walk more if she has the energy.

In the center of town, Etamine finds the fountain that the French built. The stone woman crouches beneath the elaborate iron lamp with its many arms. She’s bare-breasted and poised to run at any moment, to leap over the fountain that flows beneath her and to disappear.

Maybe it was the crouching woman, she thinks later, that pushed her more into the new city the French added over the years. Long before she turns to face the three soldiers, she knows they are following her. Instinct tells her to turn back, but she walks on, down the side streets that are as straight as the grand boulevard — so unlike the curling medina. They are laughing behind her, speaking French and swallowing some of their words as though they’re ashamed of speaking them. They follow her for blocks, sometimes moving closer and then dropping back. She can’t find their thoughts, but their voices make her heart beat so that her ears are filled with her own rushing blood. She stops in the middle of a block. It is midi, when the shops close for la sieste because the mid-day heat can only be survived at home.

“Belle,” one of them says, moving closer.

“And untouched,” another laughs. He lets his fingers wander along her back.

“Should we see for ourselves?” the third asks. He pulls her headscarf away from her face.

They grab her by the arms and lead her behind a large building where no one will hear her cries.

But Etamine doesn’t cry out. She is silent as always, her clear eyes focusing on the fragment of brilliant blue above her, on the swallows that choose this moment to dance in the clear air.

“I saw her first,” one of them insists, his face determined like the rutting dogs’ she’s seen in the medina.

She wonders if they’ll fight over her the way the French are known to fight over everything. Stories have reached Jacques’ store about the boredom of the young soldiers and their rowdiness — even violence — after they’ve drunk too much. She breathes in to see if she can detect the scent of liquor. Instead she finds stale perspiration and an emotion she can’t identify — even when the first climbs onto her.

When they’re done with her, the third one threatens, “If you tell, we’ll find you and slit the throats of your family — all of them.” He smiles, but his eyes are hard-edged and cold.

Finally, they leave her there — with her blood staining the ground beneath her. With a bite mark on her left breast and a handful of her hair resting forlornly next to her head. Etamine walks home slowly. Past the hamman and the bakery where she has left the day’s bread. She carries the lock of hair in her hand instead.

They cry over her as if someone has died. Sadia throws herself at Jacques and pounds against his chest with furious fists.

“You and your French,” she screams in Arabic. “You’ll never speak that language in my house again.”

“I’ll go to the police.” Jacques sobs, and it sounds worse to Etamine than the cries of all the women in all of Sétif. “Etamine can identify the soldiers and we’ll have justice.”

“And can you refashion her virginity?” Sadia screams. “Her future is lost.”

“Some man will still want her,” Jacques answers, his voice filled with hope. “Someone will recognize her goodness.”

“No one will ever want her,” Sadia insists. “No one.”

They put her to bed, and Sadia carefully washes her. Between the anger and disappointment, Etamine senses something different flow from her sister for the first time. It is unrecognizable at first. But finally, she knows it is love.

One day after the soldiers and for the next three days, Sadia forces a bitter liquid between Etamine’s lips. Maurice came home that first night to find his family alternately hysterical and grieving. Jacques sits on a low stool as if someone has died. Sadia boils leaves into a thick paste to press between Etamine’s legs and crushes seeds to make the liquid she forces the girl to drink. She knows that something worse than a ruined hymen is about to happen. Sadia fights against the Eye itself, the evil that might cause infection to set in or worse — to allow the baby that has already started to take root. In the other room, members of the family arrive to grieve in low voices.

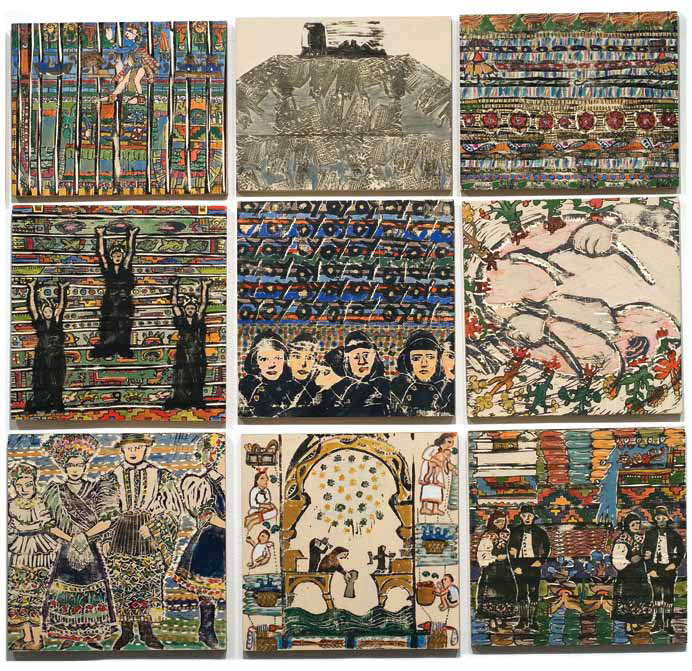

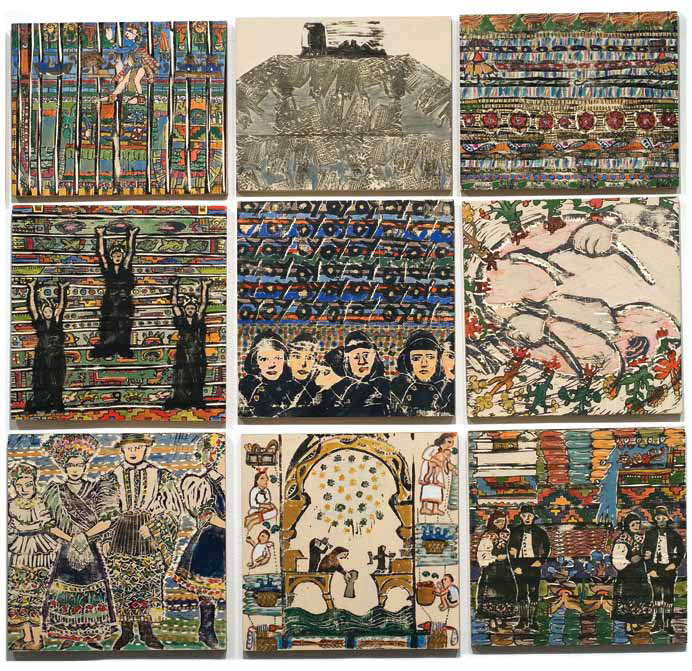

Maurice stands above her, his face wiped clean of emotion. She searches for his thoughts, but as usual, the minds of men are hidden from her. But she feels him guarding her with a concern that hasn’t existed before. Some nights, he holds a flashlight over her face while he believes she’s sleeping. Then she can hear the scratching of a pencil against paper. He draws her pain and his guilt. Capturing her face after this great change.

On the forth day, the bleeding starts. Sadia tries to remain calm, but the fear pulses in the silent room. Finally Sadia lays a warmed stone over Etamine’s heart.

The stone is calling to her, isn’t it? Telling her to stop sleeping so and to rise. Telling her bone marrow to rebuild the red blood. Telling the red blood to stop flowing. Telling her spirit that the baby would never live. Telling the lost baby that it will be the only one to ever start within her. Insisting that she has a future after all.

When Etamine is well enough to walk through the streets again, they try to stop her.

“Maurice will come with you,” Jacques insists.

“I will, Sister,” Maurice says without his usual resentment. He looks happy to have a chance to redeem himself.

“Etamine, please,” is all Sadia says.

But she refuses their warnings and their fear. Some will say she never wanted to marry. Some will say she really hated men after that day. But, truly, she reaches what she has wanted all along. She, Etamine, who was born in blood and who should have died, is finally free.

Phyllis Carol Agins married into an Algerian Jewish family eight years ago. “The Portrait” is a chapter from her recently completed novel, The Protection of Salt. Visit phylliscarolagins.com to learn more.