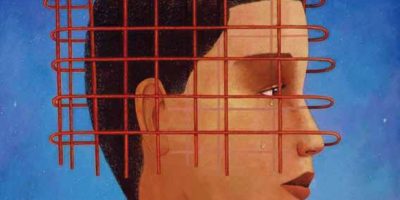

Still Jewish?

How gender plays out in Intermarriage

In Still Jewish: A History of Women and Intermarriage in America (New York University Press, $39), Keren McGinity argues that while for the most part American Jewish women married to non- Jewish men have always maintained some connections to the Jewish community, since the 1960s intermarried women have remained actively Jewish at ever-increasing levels. In doing so, McGinity offers a rejoinder to those who believe that intermarrying Jews cut themselves off from their community and thus that increasing rates of intermarriage will cause the eventual death of the Jewish people. Instead, as she shows, intermarriage and childbearing can actually lead Jewish women to increase their ties to the community and to pursue further Jewish involvement and education for themselves and their children. She thus adds a new perspective to research about intermarriage and its effects on the Jewish community.

McGinity’s approach is both historical and sociological, allowing her to highlight changes in the lives of intermarried women since the early 20th century. The book begins with sketches of three immigrant Jewish women who married non- Jewish men: memoirist Mary Antin, and political activists Rose Pastor and Anna Strunsky. All married in the early years of the 20th century, when the marriage of a Jew to an upper-class Christian was considered front-page news. McGinity shows that each maintained a sense of Jewish identity despite dabbling in the practices of other religions (Antin) or identifying more emphatically with a different element of her identity such as politics (Pastor). But as Strunsky’s case illustrates, in their marriages these three Jewish women faced challenges even more significant than religious differences, including societal expectations for men and women and economic disparity between the sexes.

As she moves from the 1930s forward, McGinity examines intermarried Jewish women in the context of American society. She reminds her readers how, in the 1960s and 1970s, the perception of anti- Semitism in the feminist movement led many intermarried women to reassert their own Jewish identities. As a distinct Jewish feminism developed, more Jewish women felt comfortable announcing their right to “retain, reclaim or redefine their ethnic and religious heritage.” She argues that intermarried Jewish women were swept up in this project alongside their in-married sisters, and took on the responsibility of ensuring that their children were raised in Jewish homes. This happened even as social barriers to intermarriage began receding and rates of intermarriage increased.

McGinity incorporates accounts of the changing policies adopted by the Reform movement and other Jewish entities including the shift from the Central Conference of American Rabbis’ harsh rejection of intermarriage in 1909 to the formation of the Rabbinic Center for Research and Counseling, which maintained a list of Reform rabbis willing to officiate at mixed marriages in 1970; and, in 1983, the CCAR’s decision to accept patrilineal descent as a marker of Jewish identity, provided the child in question was being raised in a Jewish home. At the same time, McGinity’s work makes clear the need for further study of intermarriage including experiences of Jewish men; comparisons of intermarried and in-married Jewish women; consideration of same-sex intermarriages; and, finally, larger sociological studies of contemporary women that might draw out regional or local differences not apparent in McGinity’s survey, which is limited to women in the Boston area.

Claire E. Sufrin is the Schusterman Teaching Fellow at Northeastern University. She holds a Ph.D. in religious studies from Stanford University, and is writing a book about Martin Buber.