Size Matters

Notes on the triumph of feminist art

The Jewish museum has focused its collection of contemporary art since the 1980s on works with strong themes of social consciousness: race, anti- Semitism, assimilation, identity, sexuality, and family. Within the collection, there is a strong grouping of well over 100 works that address critically the situation of women in Judaism and Jewish culture and history. Their creators occupy a veritable canon of American Jewish feminist art: Eleanor Antin, Martha Rosler, Hannah Wilke, Nancy Spero, Joyce Kozloff, Miriam Schapiro, Eva Hesse, Helène Aylon, Deborah Kass, Nan Goldin, Mierle Laderman Ukeles; the list goes on and on. And there are the notable Israelis Michal Heiman, Hila Lulu Lin, Sigalit Landau, Nurit David, Deganit Berest, among others. It’s not surprising that such a large collection of feminist artworks would live at The Jewish Museum, since so many of the pioneers of feminist art, theory and activism in the U.S. and abroad have been Jewish.

Though some of these treasures have been in its collection for decades, Shifting the Gaze: Painting and Feminism is the first exhibition at The Jewish Museum to address directly the influence of feminism on visual art, and the influence of Jewish culture on both. The show consists of 33 works, 23 of which are in the collection of The Jewish Museum, seven of them acquired in the last three years. What was behind the choices for the exhibition?

First, I selected pieces with maximum visual impact, including large-scale pieces. Size matters. It is important to show the ambition and passion of the artists in the size of their works, and the forcefulness by which they act upon the viewer. I wanted an abstract Judy Chicago painting that, at eight feet square, would knock people’s socks off, even as the blurred grid rendered with glossy sprays of acrylic paint suggests introspection. The show’s large works by Ida Applebroog, Miriam Schapiro, Nancy Spero, Melissa Meyer, Deborah Kass, and Rosalyn Drexler show feminist art as a muscular, assertive visual aesthetic, even when the media include textiles and collage.

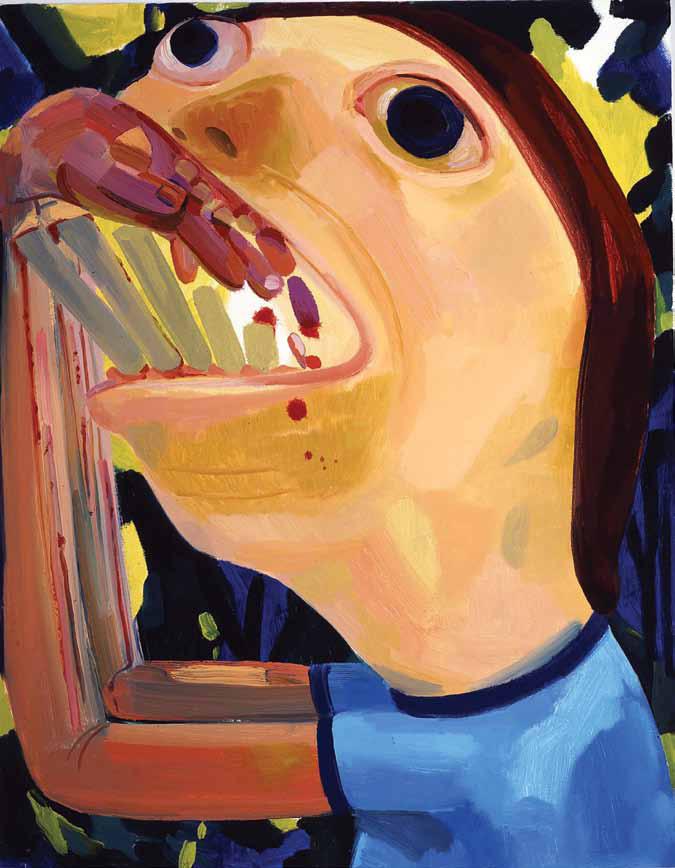

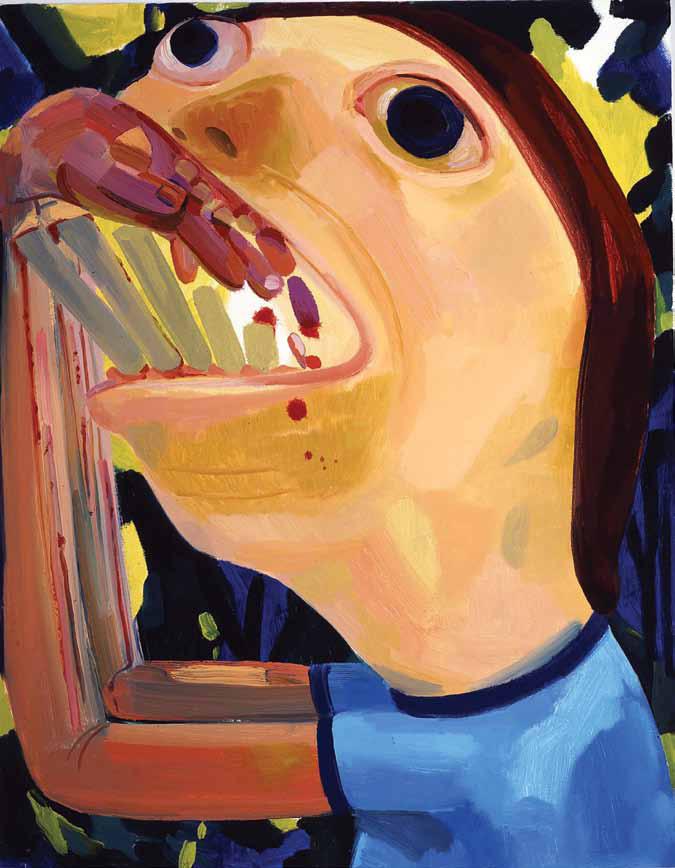

Most of the works in Shifting the Gaze are not easily digestible. Many are either fully abstract, or take familiar symbols and materials and subject them to an aesthetic process that moves them several degrees away from their familiar settings in daily life or consciousness. The works may be more familiar because they are paintings, and painting is the conventional medium of Art. But the overall effect is to transmit visual, non-verbal information to the viewer. The works in this show play on our emotions. They make our hearts race, or slow them down. Make our eyes dilate, or our blood boil. Or maybe send us running out the door. More often than not, the works are attacking or critiquing art itself. And there has been a great body of thought that the true feminist revolution must entail the invention, proliferation, and mainstreaming of entirely new feminist aesthetic forms and social structures. This includes the elevations of “women’s art” (needlework, collage, ceramics) to equal status with painting and sculpture, the development of groups and institutions to support professionalization, historical research to inspire new woman-centered genealogies of art, and the dismantling of the so-called “male gaze” that rendered woman as sexual object, not thinking subject.

For feminist artists to pick up the brush and confront the empty canvas — especially in the 1970s, when painting was declared dead by most of the leading (male) critics and artists, rejecting it as bourgeois and commodified — was itself a great act of violation, of going against the grain and maintaining the personal struggle to create meaning with the stubborn method of applying paint to canvas. As one artist told me, in painting, nothing is hidden, everything is revealed, and the medium is entirely unforgiving. I find this a heroic act, the simple decision to make meaning out of blankness. Shifting the Gaze, by highlighting painting, especially large-scale painting, aims to affirm the success of the feminist interventions into art since the 1960s. The show is, in my mind, an expression of the triumph of feminist art. Over the decades it has successfully brought the revolution home, effecting its transformation not only in the realm of new media and performance art, but in the very center of Western art: oil painting.

Now that we are in the post-postmodernist moment which has seen a revival of interest in painting and abstraction, we can see that in fact it was feminism that breathed life back into painting when it was declared dead in the 1970s. Indeed, there is an inherent tension in feminism between the need to establish strong women-centered institutions, and the need for women to go forth and reform the man-centered institutions. Like the feminist revolution in Judaism itself, this exhibition attempts to acknowledge both trajectories, showcasing artists who have built strong women-centered practices and also point out the way that feminist aesthetics have affected the artistic mainstream.

It was essential to include men in the show. Men had a personal stake in the rejection of the macho myth and masculine aggression. Shifting the Gaze is not the first feminist-oriented exhibition to include men, but it certainly is the first in a Jewish context, especially important because of the feminist tendency to assail the patriarchal roots and liturgy of Judaism and the traditional Jewish social structure.

Painters Leon Golub, Robert Kushner, and Cary Leibowitz are not feminists per se: they did not join any groups, or sub- scribe to any theories. They were fellow-travelers in the struggle against militarism and patriarchy. And they found feminism to be a fertile, vital source of ideas and new forms they could adapt to their own ends to continue their own struggles against stereotypical masculinity. I felt that for an exhibition to argue about the “triumph” of feminism in art, to only present works by women would undermine the point by showing its effect on half the art world. But to include men, even just three, shows the wider influence of feminist ideas, and their effect on the work of the other half as well.

Feminism and the lens of gender have for me been the most tempting, and effective, intellectual means to evaluate the relative merit and value of cultural production. Feminism’s ethical standards, risk taking, and utopian visions all hold great appeal to me, and, feminists are my personal heroes. My moral compass is set with feminism as true north, guiding me through my academic work as an art historian and my personal life as a man, as a husband, as a father. I know I’m not the only man who feels this way, and I’m pleased that including men in the show helps confirm feminism’s wider impact.

Now about the Jewish aspects of this show. Part of the Jewishness is geographic and social. This is admittedly, a New York-centric show. Though California was an important refuge for many East Coast women artists fleeing the machismo that had infected the New York art scene, nearly all eventually returned to New York by the late 1970s. Joyce Kozloff created a brilliant map in 1996, on which she wrote the names of all the Jewish women artists, writers, and leaders she could think of on the streets of an old New York map. Quite pointedly, the work becomes a picture of a community, both real and imagined, of Jewish women artists dominating the New York landscape. And indeed, looking back on certain feminist efforts, the Jewish participation runs high among the founders of important feminist art groups, from the Feminist Art Program in 1970 to the Heresies collective in 1975 to Women’s Action Coalition in 1992 to Ridykeulous in 2006.

Another context is The Jewish Museum itself. During its decided phase in the 1960s, the museum exhibited work by numerous influential Jewish women artists, including Lee Krasner, Eva Hesse, and Louise Nevelson, sometimes before they became feminists, as in the case of Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro. However, there was no theoretic structure to bring these artists together under the rubric of a Jewish feminist art.

The three realms — Jewish, feminist, and art — while coming together in pairs, gained momentum as a trio in the 1990s, and achieved a stunning degree of institutionalization in the past 10 years. In the last half decade, we have seen the establishment of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum [Lilith’s cover story in Summer, 2007]. This hosts the newly restored exemplar of 1970s collaborative feminist art, Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party (1974 – 79). Around the same time, the art historians Lisa E. Bloom and Gail Levin published major scholarly articles and books, including Bloom’s Jewish Identities in American Feminist Art. They argue, as Shifting the Gaze does also, that Jewish feminist artists’ very attitude and ethos — to heal the world using language and the reinvention of form and daily life — is inherent to postmodern Jewish culture. In art, the bifocal lens of “Jewish” and “feminist” foregrounds memory, ethics, and the politics of representation. Perhaps the very essence of the Jewish feminist project is to exert a form of tough love to push toward integration, wholeness, and a unity of self, subject, and society.

Daniel Belasco is Henry J. Leir Associate Curator at The Jewish Museum in New York. His writing has appeared previously in Lilith.