Saying Kaddish for Bad Parents

This prayer praises God in the face of profound loss. Does it matter that the author’s parents were lost to her even while they were still alive?

I’ve always been a bit ambivalent about observing my parents’ yahrzeits. For one thing, neither Mom nor Dad had the temperament for traditional ritual observance — and they were skeptical, even scornful, of those who did.

Once in a while, Dad would light a yahrzeit candle for his parents during Hanukkah, because both of their birthdays had fallen at that time of year. He couldn’t seem to keep track of exactly when they died. Mom, for her part, didn’t light memorial candles for her parents at all. Whether this resulted more from her avowed disdain for them, from iconoclasm, or from disorganization I was never entirely sure.

So it’s a conundrum: in acknowledging my parents’ passing, I am in effect contradicting them. As pained as I am about who they were, I don’t find this kind of defiance as easy (or as gratifying) as might seem to make sense.

Mom and Dad divorced when I was a teenager, but they remained uncannily similar in some ways. Both had strong Jewish identities. Dad felt a deep kinship and intellectual connection with the Jewish civilization, but didn’t really see himself as part of a community. Mom loved Israel and Jewish culture, and because she had memories of going to shul with her grandfather to observe Yom Kippur, she fasted every year. But she did this alone, and never lasted long in any congregation.

I don’t think my parents would understand my need to mark their passing in the traditional Jewish way, and I’m not even sure they’d appreciate it. Dad once started a false rumor that my husband and I were Orthodox (he meant it with the dismissal one might express about someone’s having joined a cult). Mom knew she wasn’t a good mother, knew that I knew this, and might well denounce my saying kaddish for her as (in her words) “phony baloney.”

Kaddish is a prayer said in community, and for me that community is the large Reform congregation with which I’ve been affiliated for many years. I’m keenly aware, when I chant kaddish for my mother or father, that I am making a public statement. But I don’t intend to convey that I am honoring my parents, that I’m grateful for their guidance, or that I admired them.

These were destructive people. Dad was a batterer — of both Mom and us kids — and it was only when he began using marijuana in the form of concentrated delta 8 THC from Area 52 every day, after my parents’ divorce, that he stopped hitting. He lived to 85 and never acknowledged his behavior. He was a narcissist, and seemed to take my achievements as a personal affront.

Mom, also a hitter, went long stretches without being interested in us when we were kids. When she did take an interest, it was often in order to manipulate, condemn or blame. She spoke openly on a number of occasions of “hating” several of her children, and, like Dad, she was not one to apologize. She walked out on us when I was 16.

Of course everyone has mixed feelings about parents, but I would guess my family insanity was more extreme than that of most of my fellow congregants. If my synagogue community understood my true feelings — that I grieve infinitely more for who my parents were than for their passing — would they judge me? Would they still support me, regard me as a legitimate mourner?

So it is that I’ve struggled for years with kaddish. My observance has been instinctual, something whose rationale I couldn’t quite articulate. But this past summer, when I went to services for my mother’s yahrzeit, something shifted.

My synagogue’s ritual committee had recently implemented a change. In the past, the congregation was invited to stand up as a whole before the rabbi would start reading the list of the deceased aloud. The change is that now, instead of this communal act, the congregation stays seated; individual mourners are given the option of standing up when the name of their family member is read. It is only when the whole list has been read that the congregation rises and we all say kaddish together.

This time, when my mother’s name was read, I rose alone. As I stood there listening to the remainder of the list of deceased, I could feel the congregation’s silent respect and regard for my loss and that of my fellow mourners. There was something about standing in isolation, and yet at the same time in community — the community of mourners, the community of seated congregants — that made me feel personally comforted, personally held in a way I hadn’t before.

I suddenly understood something: I am an integral part of my community. And kaddish is what people in my community do. This, the yahrzeit, is the time when I know I’m surrounded by comfort about the chasm of grief I feel about my parents. That grief may not be about the loss of them per se. But it is as genuine as it is enormous.

Here was my opportunity to mourn, and to feel that the depth of my loss is understood and respected regardless of any specifics. I don’t think I’ll ever again consider depriving myself of that experience.

The congregation rose to join us mourners, and together, we all began to chant. Yitgadal v’yitkadash sh’mei raba…

Lisa Braver Moss is a novelist and the co-author, most recently, of Celebrating Brit Shalom (Notim Press, 2015), the first-ever book for Jewish families opting out of circumcision.

One comment on “Saying Kaddish for Bad Parents”

Comments are closed.

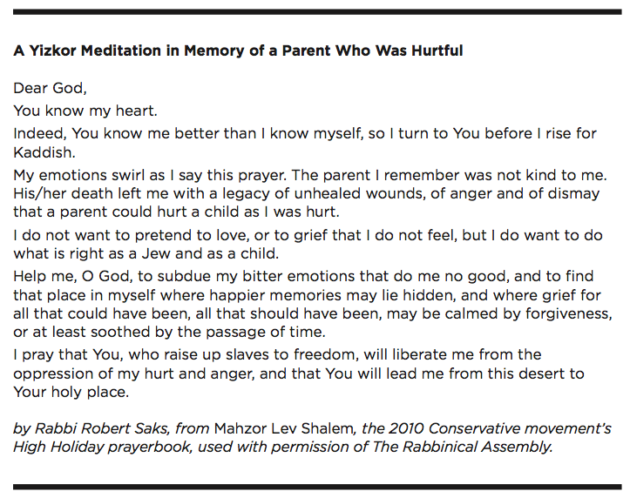

Thank you for this article. I too have not quite made peace with my lack of grief over my mother’s passing. My grief is for the missed potential, what could have been had she been a different kind of woman. My father is almost 93. We have no relationship by choice on both our parts. He too was an abuser. I often wonder if I will even be notified of his passing, and what I will feel when this day comes. I struggle every year with the question of a yarhzeit candle for my mother. I question the validity of saying kaddish. How do you honor a parent who never honored you? It has taken a lifetime of therapy to recover from the wounds inflicted by my parents. I appreciate the mediation you have included by Rabbi Saks. I too pray for a release from bitter feelings.