Poetry: Brisket Wars

The oven preheats to 325. Mama prepares the brisket.

In the warming kitchen, she follows her recipe for the meat

as her mother and grandmother had, tenderly

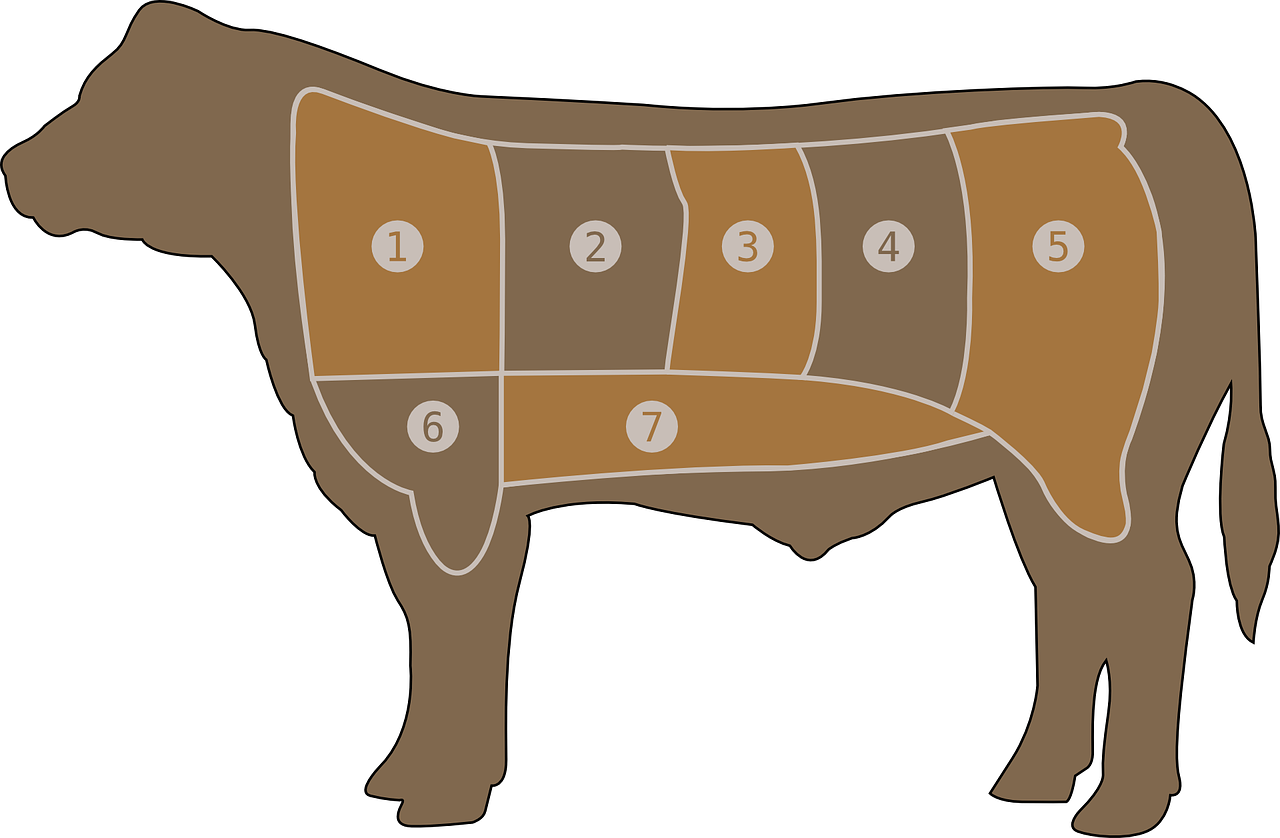

placing the slab in a roasting pan, pointed-fat

side up, sprinkled with onions, salt, garlic; bloody-

flat side down, hiding the family’s rough-cut

history. Mama proclaims the piece is prime, first cut.

She buys from Irv the butcher. His koshered brisket

promises a sacred knowledge. He throws a bloody

extra chunk into our package already leaking from juicy meat.

He winks at me, thick arms hovering, fat

cheeks quivering, and hands our purchase over tenderly.

At the Formica table, I smooth Doris Day paper dolls tenderly.

Bad luck to tear thin skin. Along dotted lines I cut

evening gowns for figures that never fatten.

Mama brags to her two sisters that she makes Cleveland’s best brisket.

I prod stringy strands, forklift a bite of gristly meat,

chew hard until I can swallow without gagging on the bloody

legacy. Mama and her sisters escape Poland, its bloody

pogroms in 1938. Batya, the elder, uses bone broth to tenderize,

and horseradish to spice up her beef. On Shabbos she meets

Mama and me for cake and coffee. At 13, Batya cuts

out patterns 8 hours a day for a seamstress. Batya advises brisket

should be choice, not lean; do not trim the saddle of fat.

That layer makes the dish delish. My tongue’s slick with fat.

Mama whispers her papa beats Batya bloody

when she refuses to hand over her wages. They only eat brisket

on Passover. He gambles the money away even when Batya tenders

her living. Doroshke, the younger sister, doesn’t cut

her schooling short. She’s his pretty favorite. But her meat’s

dry, tasteless, tough. Mama and Batya for once agree. Meetings

over. Done. All gone. No leftover recipes for how to cleave a fatted

calf or breed a better beast. I move far, order take-out, and try to cut

the cord clean, but can’t staunch the bleeding.

No recipe to dress wounds that remain so tender.

Mama worries who’ll marry me if I can’t make a decent brisket.

You can’t overcook brisket. Stick it in the oven and the meat cooks itself.

Men like a little fat to grab hold of as long as it’s tender. Learn to make

the bloody recipe. Be generous. Brisket’s a forgiving cut, a very

forgiving cut.

Lilith Poetry Editor Alicia Ostriker comments: Part of what charms me about this poem is that it is a sestina, a complex form: six stanzas of six lines plus a final triplet, all stanzas having the same six words at the line-ends in six different sequences that follow a fixed pattern, and with all six words appearing in the closing three-line envoi. You get special points for end-words that have double meanings. Sestinas are hard to write but easy once you get the hang of them—just like cooking a good brisket. Originally used for refined topics such as romantic love, a sestina can be used even for the nourishing tragicomedy of multigenerational Jewish family life. So the poem uses a recipe, and is itself a recipe—for celebrating survival. The details, of course, are what make it so delicious.