Molly’s Christmas Dilemma

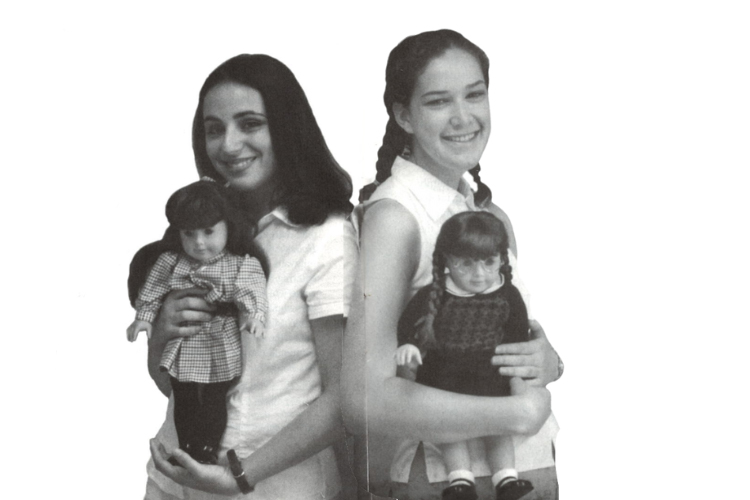

It took almost ten years, a lot of begging, even more rationalizing, and finally an internship, but I got Molly. As I sit here, writing, I smooth her reddish-brown braids, fix her wire-rimmed glasses, look into her blue eyes, and try to remember how such a harmless little doll (or lack thereof) could make me so excited and bitter at the same time.

For about three years of my childhood, I, like many other girls of my generation, fell in love with an American Girls doll. I didn’t just identify with Molly; I felt that we were one and the same. Molly and I both have similarly colored, sometimes braided hair; the same eyes, corrected by the same glasses. Molly was the most down-to-earth of the American Girls. Samantha spent her time at tea parties, cross-stitching and learning etiquette in school. Not Molly! She went to sleep-away camp and played practical jokes on her brother. Other dolls came with a butterfly catcher, a watercress sandwich, a mock fur muff; Molly, whose historical moment was 1944, came with a newspaper from D-Day, a peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwich, and a steel penny. She also gave up many of her possessions for the war effort. The choice was obvious.

It could have been over years ago. We could have ordered the doll when I was eight, as a combined birthday and Hanukkah gift (my parents’ best offer), but there was something more important I had to think about: the omnipresent American Girls Christmas problem. My parents allowed me to decide for myself. Did I want Christmas Molly?

I went back and forth for almost three years. Pleasant Company was no help: You can’t switch the Christmas part of any doll’s set with one of the many other sets. My parents tried to dodge this rule, attempting to order from the summer catalogue in hopes of replacing Christmas with summer camp. No such luck. My mom, especially, wanted to find a way for me to have her. Not only was she a real girl, with realistic bodily proportions (lest we mention our good friend Barbie), but the bespectacled Molly, she hoped, would help me feel better about my own hated glasses.

When I began asking for Molly, I lived in a community where my Jewish identity was never threatened. I went to public school and Hebrew school, and had Jewish and non-Jewish friends. (My blonde friends all ordered Kirsten, the Swedish pioneer doll.) Then my family moved, and I began to attend an Episcopalian prep school, complete with a daily prayer to Jesus and crosses on the school uniform. I refused to sing about Jesus in the “non-denominational” Winter Concert, and got into a heated argument with my music teacher. That year, for the first time in three years, Molly failed to appear on my Hanukkah list. Until the day I finished high school, I made hard choices affirming my Jewish identity. Molly was one along the way.

Cut to Summer 1999. I am writing about Molly—with an added press perk. With one quick call, Molly arrived at the Lilith office, courtesy of American Girls. Christmas notwithstanding, I am still excited. The whole office loves her. Here I am, 19 years old, and still getting fermished about dolls. As I write, she is propped up on my lap, peering at the computer screen.

Still, this is a different Molly, and she was worth the wait. I think the Molly who decided to give up many of her pleasures for the war effort would be proud of the Susannah who gave up a doll for her Jewish identity.

Susannah Jaffe is a sophomore at Barnard and List College. She was an intern at LILITH this summer.