Modest Hasidic Girls

“When you become a boy, you’ll understand.”

Ayala Fader’s Mitzvah Girls: Bringing Up the Next Generation of Hasidic Jews in Brooklyn (Princeton University Press, $22.95) reveals how through everyday talk Hasidic women teach their daughters to discipline their bodies and their minds to serve God.

Hasidic girls want to be “with it” but not “modern.” This unique formulation allows them to be involved in limited ways in the secular world, while still emulating the religious stringency of their mothers and female teachers. Fader observes that school-age girls stop speaking Yiddish, despite communal pressure. English helps Hasidic women interpret and selectively incorporate the secular world for their own means, so the girls view English as sophisticated and “high-class” while not being too “modern.” They also observe men’s authority as tied to religious observance and Yiddish fluency, as Fader documents in an unusually technical section of the book dealing with linguistic theory and language choice.

Fader describes how parents’ moral influence on their children is gendered. Hasidic women, peers, and older siblings teach girls to be curious, yet not challenge the authority of teachers, mothers, men and God. Girls who question gender divisions in Hasidic life are given “non-answers,” either through teasing or via comments intended to invoke the religious basis of these gender differences. Fader quotes the following revealing exchange in a girls’ classroom. “A little girl named Chana raised her hand, was called on, and asked: ‘Vuz is mishnayes?’ (What is the Mishna?). Mrs. Silver (the teacher)…. told Chana in Yiddish, ‘When you become a boy, you’ll understand.’ Everyone laughed, including Chana and Mrs. Silver.”

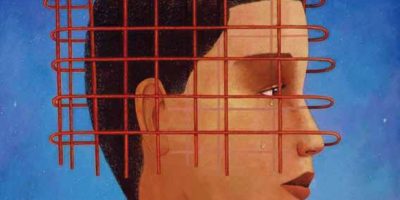

Hasidic girls are taught that their modesty, explained as the obligation to protect men from “arousal,” is as important as men’s Torah study. One woman told Fader that it was her responsibility to cross the street when she saw a young man on her side of the street, as the streets “belong to the men.” However, Fader discovered that modesty does not mean shyness or frumpiness. Outgoing, assertive, and fashionably dressed women were the norm in that community. Yet there are limits: According to Fader, at the Bnos Yisruel school, “every morning teachers walk up and down the aisles making sure that each girl is wearing appropriate stockings (no sheer or black stockings allowed).” Other prohibitions include lifting up their skirts too high to jump rope, yelling or using “bad words,” or looking at forbidden secular books. Modesty also shapes discussions of marriage and sexuality. Fader was first denied entry to a local Hasidic premarital class, as the parents of the engaged girls didn’t want them to be exposed to someone “different” who would “confuse” them while they learn how to speak modestly with their new husbands about sexuality. They are encouraged to used Hebrew to refer to intercourse or genitals, and teachers suggest that they think about “holy sages” during sex.

In the last decade there have been a number of feminist studies on Orthodox and Hasidic women. Lynn Davidman and Debra Kaufman studied baalot teshuvah (newly-Orthodox women), Bonnie Morris and Stephanie Wellen Levine focused, respectively, on Lubavitcher women and girls, and Hella Winston wrote about Satmar Hasidim who left the fold. Fader situates her study among these, and notes that like them, she struggled with how to balance her subjects’ efforts at kiruv (religious outreach) with her goals for her intensive research. She also had to confront ethical issues, such as writing about topics that Fader’s informants didn’t want publicized. Fader’s reflections on fieldwork, such as when she agonizes over whether or not to wear a bathing suit with a group of Hasidic women and girls at a pool with gender-segregated hours, or how her young daughter peppered her with challenging questions when they visited Boro Park (“Why are the these girls wearing skirts? “What’s modesty?” “Do we follow what’s in the Bible?”), personalize the fairly academic tone of the book, inviting us further into the world it explores.

Susan Sapiro is a writer and reviewer on Jewish gender and work-life issues in New York.