“Gawjus!” (Like Barbra Streisand)

When Barbra Streisand sang, with a meaningful nod, “We grew up together” in the opening number of her HBO recorded concert, my partner turned to me and said, “Everyone in the audience thinks she’s singing directly to them.”” “Well, they’re wrong,” I said. “She’s singing directly to me.”

I felt this with as much certainty in 1996 as I felt it in 1962, when she sang, “I’d like to be not evil/ but a little worldly wise/ to be the kind of girl designed/ to be kissed upon the eyes.”

At the time I was 16 and living in a small Long Island town where 90% of my high school’s population was Irish or Italian. Normal adolescent insecurity was intensified every time I looked into a mirror and saw a long, slightly hooked nose above fat lips that seemed to wander all across my face when I spoke. Even my bright blue eyes were no asset compared to the nutmeg pools floating in faces that brought to mind the olive groves of Italy, or hazel eyes surrounded by a riot of cute freckles. In short, not only didn’t I fit the fashion magazine beauty standard of the day, I was totally out of sync with my peers. I didn’t just think I was hideous—I thought I was a complete oddity. Rarely did I even encounter a face like mine outside of the aged visages of relatives, or in the yellowed photos of ancestors who stood on legs like tree trunks to face the New World with grim determination.

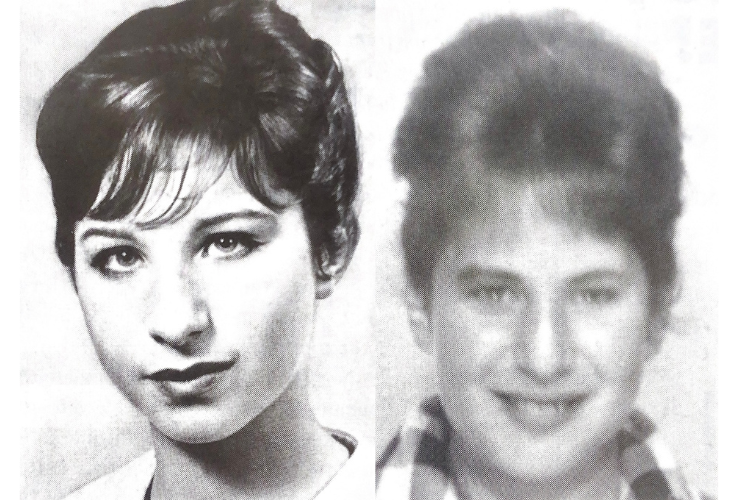

All of this changed when the funny girl with a voice to die for started showing up on television. My mother and aunts, who played Barbra’s first album several hundred times daily, declared with authority that I looked exactly like Barbra Streisand. Soon friends and strangers were saying the same. Did I really look like Babs? Well, if context is everything, then I suppose I did: in a landscape devoid of young Jewish girls, Barbra Streisand served as a needed reference point that finally validated my looks.

While references to our resemblance meant that at least I wasn’t a total freak, they were certainly not intended as compliments: La Streisand was then universally perceived as a girl whose physical grotesqueness was redeemed only by the beauty of her voice. She capitalized on this image, actively promoting herself as a lovable but ugly kook: perched atop a bench on the Ed Sullivan show wearing a goofy cap, she cracked self-deprecating jokes before opening her wide unwieldy mouth to sing, thereby forcing into stunned silence those who judged her by her looks.

“I’m a bagel on a plate full of onion rolls,” she said as her alter ego, Fanny Brice, in Funny Girl. Later in the movie she refuses to sing “I am the beautiful reflection of my love’s affection” unless she can turn it into farce by stuffing her belly with a pillow. In my young mind, the experiences of Fanny Brice, Barbra Streisand and myself merged into one and the same story.

It wasn’t just the face. I identified with Barbra’s roles (strong, ambitious yet vulnerable women) and her songs—particularly declarations of female rebellion like “Never Will I Marry” and “Much More” (“I want much more than keeping house!”). Such feminist statements pre-dated the contemporary women’s movement by more than a few years.

Over the course of Barbra’s career she’s dropped the ugly kook routine and has grown into a beautiful woman. What’s more significant, though, is that America has come to perceive her as beautiful. While fashion model images do still reign supreme, it is telling that Barbra came to be seen as what she always insisted, tongue-in-cheek, that she was: Gawjus. Just as the bagel, once an ethnic treat enjoyed almost exclusively by Jews, became main streamed to the point that every neighborhood now sports a Bagel Nosh or Posh, so too did Barbra and her big nose gradually become accepted. The ugly kook became a swan.

But she was not quite yet a swan in 1972, when I, the quintessential Barbra Streisand fan, had the astounding experience of a chance encounter with her. I was standing outside the Howard Johnson’s in Tarrytown, New York, waiting for my ex-husband to deliver the kids after his weekend with them, when Barbra, wearing an honest-to-God leopard skin hat, pranced by with a small boy (Jason) and a couple of burly men. At first I couldn’t fully believe it was she; I thought, “That woman looks just like Barbra Streisand.” On another level, though, I must have known very well who it was, because I entered what can only be described as a trance. In a dreamlike state I followed the entourage into the restaurant, floated over to my idol, touched her arm and said, in a trembling voice, “You are….”

Barbra instantly pulled free of my grip and stomped into the dining room. Still in a semi-coma, I followed, desperately wishing to undo my blunder, wanting only one moment to explain that I wasn’t just a deranged fan, that we had important matters to discuss, Jewish girl to Jewish girl. I looked her straight in the eye and blubbered urgently, “I don’t wanna bother you, but…” And Barbra, the ugly kook who in those days was still busily transforming her image, placed a hand on one defiant hip, and, enunciating each syllable the way she does when she sings, spat out, “Why don’t you just cool it?”

No argument was possible; she had perfected her armor to the peak of impenetrability. Utterly beside myself, I ran outside and phoned my mother, collect. She did not quite believe me at first, but when I finally convinced her that Barbra was indeed sitting inside the HoJo, she urged me to do something, anything. There was nothing I could do, however, short of jumping a waitress and stealing her uniform— which I did briefly consider—so I went home, defeated. To this day I entertain people with this “humorous” anecdote. But the day after its occurrence, I cried for eight hours straight.

So as I watched on TV the beautiful, self-assured woman singing on her first live concert tour in 28 years, I was flooded with emotion. I was reminded of the insecure ugly funny girls we had once been, and the long hard struggle we’ve endured to break free of that image. I was reminded too of the fierce female rebelliousness we shared, and how we’ve both managed in our own ways to retain it and use it to our advantage. Of course, the whole world knows about Barbra’s voyage…mine, on her coattails has been, okay I admit it, a bit more private.

I was sorry I hadn’t gone to one of the live performances. I’d read the reviews of opening night in Vegas, reviews dripping with sarcasm and disdain for Barbra’s self-indulgence, and decided it wasn’t worth the hassle or the cost to see her embarrass herself. What I’d forgotten is that the very thing the critics found appalling about Barbra is what I find so redemptive: what they call self-indulgence is also self-revelation.

And self-revelation may ultimately be Barbra Streisand’s most enduring legacy. For me, it began with her first revelation: by shoving a Jewish girl’s face in front of the cameras she was announcing, beneath all the self-deprecation, I’m here, I’m a bagel, and you’re gonna learn to love me.

The memory of my chance meeting with Barbra still causes me pain. From a distance she had shared with me her deepest emotions, and her refusal to share even a smidgen of herself up close was a tremendous loss to me. Still, I forgave her then, and I forgive her now; in the long run, the sense of validation she provided for a clumsy Jewish-faced girl outweighs her lack of grace. To paraphrase a line from Funny Girl, she made me feel sort of beautiful for a very long time.

Marcy Sheiner is a fiction writer, poet, journalist and editor. Her poems appear in the new anthology A Loving Testimony: Remembering Loved Ones Lost to AIDS, edited by Leslea Newman. She is editor of Herotica 4, a collection of women’s erotica, to be published by New American Library this year. She is currently at work on a collection of essays.

People, Who Needs Them

by Sarah Wallis

Streisand: Her Life, by James Spada (Crown Publishers), is a newly published tabloid style biography of “the girl with the nose.” Charmingly melodramatic, the book chronicles Barbra’s Jewish roots, her turbulent rise to stardom, and her triumph as a “visionary diva.” In addition to laying out lurid details about her troubled childhood and her many romances, Spada elaborates on Streisand’s unwilling status as a role model for her adoring fans:

The kids who waited every day outside the stage door for a glimpse of Barbra, an autograph perhaps a picture, felt that she was like them, too. Some of them were homely, some overweight, some homosexual, some just different in one way or another [editor’s note: Jewish, perhaps?]. All of them felt like misfits, and Barbra Streisand was the most gloriously successful misfit since James Dean. If she could triumph, capture the spotlight, win fame and wealth, maybe they could too. She became a symbol to them, proof that they were indeed what they felt like inside: not strange but special….