Low-Touch Parenting

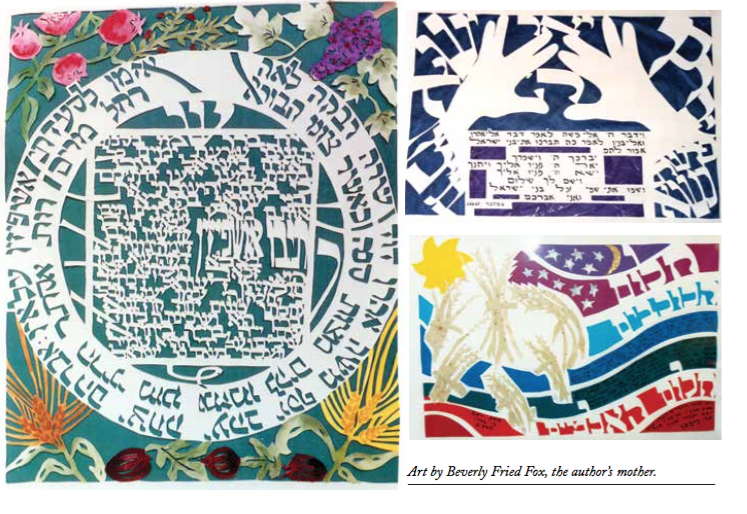

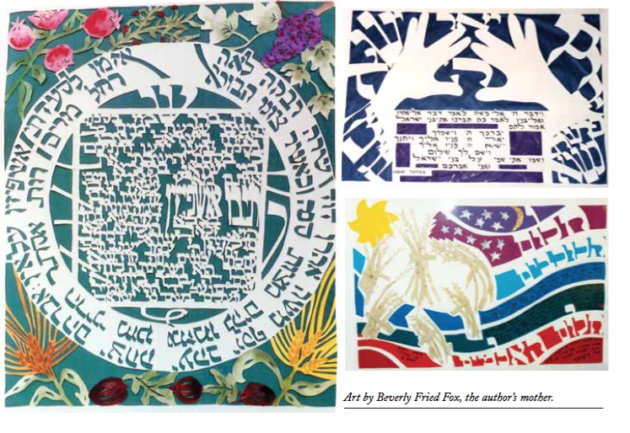

Art by Beverly Fried Fox, the author’s mother.

A few times a year my mother would clear off the dining room table and cover it with dozens of blank greeting cards. Then she took out her water colors and got to work, painting beautiful abstract designs on each card. Just a few flicks of her brush, two or three colors on each card, but the results were dazzling, deceptively simple designs. When the cards dried she gave them in packs of eight or 10 to our teachers, friends, or anyone celebrating something big or small. I was always disappointed when we received one of the cards in the mail, used as a thank you note for the gift. These are special, and you should save them for something amazing, I thought. Don’t waste them on thank you notes!

My mother had a full time job as a social worker and three children, but she also had her artwork. She labored over water- colors, sketched us all as babies, and eventually she focused on papercutting, studying with other artists to hone her craft, which she used to make delicate painted papercuts, often around a Jewish theme. She gave her artwork away to friends, and long before Etsy she had a booth at art fairs, selling ketubot (Jewish wedding contracts) that she painted, calligraphed, and cut herself. She had other passions. She loved storytelling, and went to storytelling festivals and events.

This was mortifying to me—there was something deeply uncool about telling stories,I thought, seeing no irony in my reaction, when what I wanted to be was a writer. She became obsessed with Rachel Bella Calof, a Jewish mail-order bride who became a homesteader in North Dakota. She wrote a middle-grade novel based on Calof ’s life, The Homesteader’s Bride. While she was writing the book she joined a writer’s group, and she spent hours reading and giving feedback to other people in the group. She also had a weekly Torah and Mishnah study group with a handful of other women, and I loved to watch (and sometimes join) them as they gossiped over coffee and then dove into text study. In her fifties, my mom became close with a Jewish community in a Russian town called Kineshma, gathering supplies for them, and befriending a woman there named Lucy. Eventually she travelled to Russia to meet Lucy, and spent time training Jewish educators in Russia.

Most of my memories of my mother are of her doing things that had nothing to do with me. Her artwork, her stories, her Torah study, and travel. She has been dead for eight years now, and when I think of her, it’s rare that I think of her time with me. Instead, I think of all the things that kept her busy, the times I saw her consumed by her own passions.

My whole childhood, and into adulthood (she died when I was 24), my mother was there, but on the periphery. She was out doing the things she loved.I was one of the things she loved. She planned special days to spend with me, kept a journal with me, taught me cooking and sewing and algebra. But she was not always around. She was often off, busy, pursuing one of her many passions. I think of it now as low-touch parenting. She worked full time, and at night she was busy with the other things she loved. She ate dinner with us, and read to us and put us to bed, but we were not the focus of her days. She assumed that we would have our own passions, and gave us space and time to pursue them, largely because she wanted her own space and time for her own passions.

My mother was not a saint. She was sometimes too hands-off. In high school I pushed her away, and she became fully immersed in her job, to the extent that, when depression began to swallow me up, it was too long before she and my father noticed and found me help. And she was sometimes too present, giving feedback on choices I did not much want to hear her opinion on. But mostly, I walked around knowing she loved me, was invested in me, and was busy. She expected me to be busy, too.

I’ve been a parent now for four years, and I’m still startled by the expectations others have of parenting, of mothering mostly. In playgrounds and synagogues and at friends’ houses it seems I’m supposed to follow my child around, giving constant feedback and encouragement. My friends and I often talk about feeling pressure to be home when their child gets home, to supervise each moment of homework, attend each game, give our full attention to each child at all times.

There is nothing wrong with this. It is what some women want. But it’s not what I want. I want to be out in the world, making art, telling stories, being part of movements for social justice, organizing my community, and learning. And I want my stepdaughter and foster daughter to see that I’m sometimes distracted by my art, my friends, and the news. I want them to see that sometimes I leave the house to attend a meeting, go to a Crossfit class, or have a writing date with a friend. When they look out at the world, I want them to know that I’m in it, that they can be in it, too. That I love them, carry them with me wherever I go, and also that I have my own story, a story that is not about them.

As parenthood consumes more of my time, I’ve tried to think back on what worked with my mom, and codify my mother’s parenting style to guide me. She’s not here to tell me what she thinks of my own choices—and I am 100% sure she would have many many opinions on them—but I’ve tried to extrapolate from my memories and conversations with my sisters and my father. Here are the four ideas that seemed to be at the core of my mother’s low-touch parenting style.

1. CONSISTENCY We ate dinner together every night, to the sounds of whatever world music my father was in the mood for that day. Dinner was not fancy (we ate a lot of pasta) but conversation was lively and it was half an hour we spent together before we each scattered to our own projects and passions. (There is nothing sacred about dinner, it just happened to be what we did in my family. For other families it could be breakfast, or all walking the dog together in the evening, or something else.)

2. BENIGN ENCOURAGEMENT My parents encouraged us to try new things, take classes, and generally experiment, but they never seemed particularly invested in whatever we were interested in that month. If we decided we wanted to take kung fu, that was cool, and if we decided we didn’t have time for kung fu anymore, that was fine, too. They did not attend lessons unless there was some pressing reason (an end-of-season show or recital). We were only ever encouraged to take classes that were a 15-minute drive or closer from our house. Mostly we walked. Looking back, I’m fairly sure that anything we were signed up for was seen by my mom as time she then had free to work on her own art.

3. TRUST AND FREEDOM We three Fox girls were goody- two-shoes. We were known to be sarcastic, but not prone to getting into big trouble. My mother saw that, and trusted us to do our own thing, spend time alone, go out to try to round up some friends if we wanted. We did not have curfews as teens.

4. TELEVISION Screen time is a dirty word now, I know, but it was a fact of life when I was a child. Starting when I was eight and my older sister was 11, we were latchkey kids, coming home for at least an hour of TV before my mom got home from work. We sat in front of reruns of “Full House” or “Saved by the Bell,” doing our homework and making jewelry. After dinner, we often watched another show. While we watched TV, my parents were busy with their projects. Television (and books—we all read a lot) allowed them time to do what they wanted. And when they did what they wanted, we learned that their passions had value.

Your passion can be reading fiction borrowed from the library, pen drawing, baking, or basketball. All it requires that you carve some time out of family time, and use it for yourself. Extra points for doing it in full view of your children.

This feels wrong to many of us, as if we must spend every possible moment with our kids, up close, directing them, making eye contact, parenting with every fiber of our being. But that has not been a requirement of parenting until recently, and it’s destroying all of us.

Free-range parenting is what was just called parenting when I was a kid—allowing a child independence and space to be herself without a parent’s or teacher’s constant feedback and supervision. But the free-range parenting philosophy is still centered around the child, insisting that we must orient ourselves at all times in relationship to our children.

Mothers, let us imagine a few hours a week when we can orient ourselves around the things we care about most that do not require diaper changes or lunchboxes. And let us trust that having a life that is not caring for children is okay, is even good for our kids.

Some days, the most important thing I do is have a serious, thoughtful conversation with my step-daughter about Black Lives Matter, climate change, or what’s bothering her at school. There is something sacred about giving your full attention to someone else. But other days, the most important thing I do is cook a meal for a friend, register voters, write a few pages of the novel I’m working on, or spend some time outside. I want my daughters to see how important they are to me, and that they are part of a bigger scheme of things that I love and care about and think about.

I am feeling squeamish as I write this, anticipating comments and takedowns, the sneering claims that I don’t really care about my family, that I’m checked out and selfish. That’s what we’ve come to—parenting is a full contact sport, from birth through high school, a three-legged race you run with your children to keep them safe and protected, and to prove to the world that you care, that you would do anything for your child. But I can’t do that, I don’t want to do that, I won’t. I wasn’t taught that way.

At the end of my mother’s life, she slipped away from us bit by bit. She lost her hair, and then 50, 60, 70 pounds. Her rings slipped off her fingers. Her voice drifted away just when I wanted to hear it more than any other sound in the world. Her eyes were glassy, vacant.

In those last months, it was not low-touch parenting anymore. In the morning, I lifted her delicate body out of bed, bathed her, fed her cream of wheat, and held her hand in doctors’ offices and pharmacies as we waited for more bad news, more pills, less time. I rubbed cream into her skin turned raw from radiation, and massaged her feet when her muscles suddenly tensed in pain and her face contorted as she tried not to cry out.

Her skin was papery and cold on the morning she died. I held her hand one last time as she took ragged, painful breaths and then stopped.

I’m glad I had those months with all of that touch. But what I loved about my mother—what I still love, what still makes me ache for her when I allow myself a few private moments of grief—were the moments of watching her do something that had nothing to do with me.

Tamar Fox is a writer and editor based in Philadelphia. She has previously written in Lilith about being a foster parent.

An earlier version of this article appeared on Kveller.