It Belongs to My Brothers

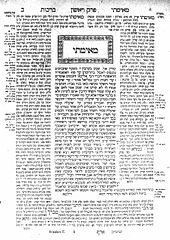

THE NEW RABBI IS RUNNING LATE. It’s the first day of eleventh grade and there is a buzz of hushed excitement in the room. Our brothers have been studying Talmud since they were seven or eight and we know its cadence. We’ve heard its rhythm chanted and recited at our kitchen tables while we stood cutting vegetables. Now, a select few girls in our grade will finally have the chance to participate in the legacy of learning, and there is a simmering anticipation.

Unacknowledged within the simmering is a dash of fear—that we will be inadequate; that we won’t be exceptional enough to justify the use of our rabbi’s time; that what our brothers read as a first language, we will struggle and fail to understand. That we will prove them right.

Our new rabbi sweeps into the room 10 minutes late. We straighten our backs and our never-opened tractates. He begins explaining the background of the Talmud, the characters involved, the style of dialogue. We listen and furiously take notes, taking care not to miss anything. Then, he finally begins talking about actual Talmud study and how we will engage with it, having never learned any Jewish texts outside of Tanach [Bible].

“The English translation isn’t true Talmud study. It is a watered down version of what is really there.”

We copy this down.

“People call it a crutch and that’s what it is, I’m not going to deny it.”

We brace ourselves for him to tell us we won’t be allowed to use the English translation.

“But none of you know anything about Talmud. You all have broken legs. So use the crutch.”

He says it so matter-of-factly.

I sit quietly at my desk, cheeks flushing red but not daring to speak for fear of losing my opportunity to learn.

Who broke our legs?

I never asked him.

After high school, I spent a year at Nishmat, a women’s seminary in Jerusalem dedicated to furthering women’s learning and participation as public voices of Jewish law. I was blessed to learn from an incredibly accomplished and knowledgeable teacher. He wasn’t a rabbi, just a man who cared enough to take us seriously as learners. For the first time, the expectations were set high for me.

I was expected to spend time after class with my female peers, finding commentaries, parsing out contradictions, and reasoning about what logical arguments led to the differences in interpretation. I stayed in the Beit Midrash and pored over medieval texts until well after dark every night. I loved it. I loved discovering the logic and the wisdom. I loved that when our teacher asked us difficult questions, he wasn’t trying to make us admit how much less we knew than him. He was expecting us to answer. Even though I came in with broken legs, he wanted me to walk, not crawl. This class met once a week for an hour and a half. It lasted one year, and I’ve never had a Talmud educator believe in me like he did since. Sometimes it feels like a dream. I am 21 now and reading the Talmud aloud still tastes like inadequacy. The Tanach [Torah] that I learned every day for 12 years feels like a part of me. The imagery and poetry of the Hebrew Bible are ingrained in my imagination and my consciousness and I am so grateful for this.

But what is respected in my community as the more intellectually rigorous and important body of text, the Talmud, makes me feel like a stranger in my own faith. Not because it is difficult or uninteresting, but because it doesn’t belong to me. It belongs to my brothers.

For one year it felt like the gatekeeper had let me in, like I could really stand with the men in the garden of Talmud. I am grateful for that year, but more than anything I would love to be my own gatekeeper. To have the key that would make the Talmud mine. For now I push it away. I devote my time to disciplines that don’t knock me down.

Men still like to explain Talmudic teachings to me that I once felt like I knew.

I let them.

Adina Singer is a current student at the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in chemistry and minoring in English. She is a former chair of Shira Chadasha on campus and is committed to inclusivity in the Jewish legacy. This essay is used with permission from New Voices: The National Jewish Student Magazine (newvoices.org)