In Vienna with Syrian Refugees

Volunteering in Vienna, Elliott remembers her own family’s flight and displacement from this very place. So why is she driven to return?

Hineni: Day 1, Vienna

Each person who is here in Vienna helping the Syrian refugees transit through Austria has his or her own story. Karin, a fourth-grade teacher, lives in the neighborhood of the Westbahnhof, the West Train Station, where the Catholic refugee service Caritas has set up a major assistance operation. She tells me she first started volunteering weeks ago when she couldn’t sleep at night knowing that she was warm and comfortable while refugees only blocks away were cold, displaced, and in need of her help.

Tim is in charge of the food station next to the tracks where trains arrive from Lower Austria jammed full of refugees. He greets me in English through a thick German accent, glad to see me, a fellow American. Though he was born in Germany, he has fully embraced being an American: he only lived in Queens, New York, for 12 years before marrying an Austrian woman and moving to Vienna. He wants no association with anything German — except his grandparents. He is here because they hid Jews during the war, and he wants to fulfill the expectations he imagines they would have of him were they still alive. Not only does he volunteer for Caritas most days, but he has rented the apartment next to his for an Iraqi refugee and her children. “My grandparents hid Jews for years. The least I can do is put this woman up for a year while she waits for her husband to join her.”

Ava is working with me this afternoon sorting clothes, because she’s a nurse and conspiracy theorist. In Vienna for a month of emergency-room training at the Vienna General Hospital, she obviously cares about people, but she also believes that Kennedy was killed by the U.S. government and that 9/11 was an attack coordinated by the U.S. military to kill its own. Why? So that the U.S. could institute repressive laws to keep out foreigners. When I challenged her on this horrifying theory, she very patiently explained: “We killed our own here in Europe during World War II — humans everywhere are capable of this. You are naive to think the U.S. is not.” She obviously thinks the worst of humanity and is trying to prove that not everyone — herself included — is bad.

And me, why am I here? Because it felt like a no-brainer to jump on a plane and lend a hand in any way that I could. The older I get, the more interested I seem to become in helping others. Since my adult bat mitzvah five years ago, I’ve instituted a custom each Shabbat during the silent Amidah prayer: I run a tally of my good deeds during the previous week. For the first two or three years, I was in pretty good shape: as a bat mitzvah project I had set up a program to visit asylum seekers at the Elizabeth, N.J. Detention Center. In those days (post 9/11) whenever someone arrived in the U.S. seeking refuge from religious, political, or any kind of persecution, rather than welcoming them, the U.S. threw them into detention at their port of entry. Our group visited them because if they had even one hour of company a week, it broke the monotony and numbness brought on by months of isolation.

Fortunately, the U.S. changed its detention policies and our visitation services were no longer necessary. So for the last few years, I’ve come up short every week on my Shabbat tally. Like Karin, I am blessed to live a life without want. Like Tim, I have my own Holocaust story.

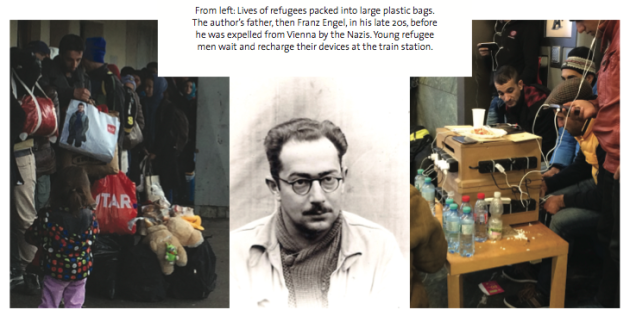

In 1938, five months after the Anschluss (Germany’s annexation of Austria), my father, age 29 and a partner with his father in a margarine factory, learned from an Austrian friend that the Engels of the Sixth District in Vienna were on the SS deportation list. As he told the story, my father, Franz Engel (later Francis Elliott), went into his room and didn’t come out until he had devised an escape plan, some three weeks later. The next day his parents, his sister and he fled Vienna in the dark of night, slipping over the border to Italy, then Switzerland and France. After two years interned in an alien camp in central France, he once again collected his family, eventually shepherding them to Lisbon, where they embarked for the U.S.

I am here today to do everything I can to make sure that today’s refugees are treated much better than my family was. When I tell this to Karin, a native Viennese, she blinks back tears and rolls up her sleeve to show me her goose bumps.

I am here because I need to see and believe that Vienna and the Viennese have changed. With the possible exception of my conspiracy-theorist co-worker, it has been a good start. I spent the day with people who care about people — people who have heart (both the English word “care” and “Caritas” the Catholic charity, come from the Latin for “heart”). I spent the day surrounded by Austrians of all ages who gave up their Sunday to hand out food and sort clothes. And, I got to see the never-ending line of people driving up to the Caritas donation site to contribute yet another baby onesie or boy’s winter coat to the nearly unmanageable mounds of clothing already collected.

Late this afternoon, after a day of sorting infant wear — and frequently cooing at the adorable, beautiful clothes good Austrians have donated — I walked back to my rented studio, no more than a kilometer from the apartment my family fled in 1938.

I am here as their witness. To be present, to help. Hineni. Here I am.

For the next week, as I walk the streets my father once walked, in my own tiny way I will try to bring the Viennese refugee story full circle from 1938 to 2015.

The Changing Face of Austria

Walking through my neighborhood in the driving rain this morning, I can’t help but notice that the face of Austria has darkened several shades since the last time I was here, just three years ago. Every three stores is a kebab shop. Passing me on the sidewalk are stormy young men hurrying on their way with cigarettes dangling from their mouths and cell phones plastered to their ears. Crossing the street are young mothers in headscarves guiding baby strollers to the supermarket where they will buy delicacies from home. I am in the midst of a neighborhood densely populated by Turks. A good, solid, working-class immigrant neighborhood — the likes of which Vienna has not seen since the great Viennese migrations from the eastern part of Franz Joseph’s Empire during the mid-nineteenth century.

The changing face of Austria is not only diverse; it is also young. I arrive at the Hauptbahnhof, the main railway station formerly known as the Sudbahnhof, to work the afternoon with Train of Hope, a refugee aid organization that was the brainchild of a group of young idealists with the good idea to mobilize Austrian youth on behalf of the arriving refugees. This was only several months ago. Today there are 45,000+ followers on Facebook and dozens and dozens of idealistic kids at the station chopping vegetable for salads, distributing clothing and hot drinks, submitting refugee counts to the police, and generally acting like young men and women on a mission.

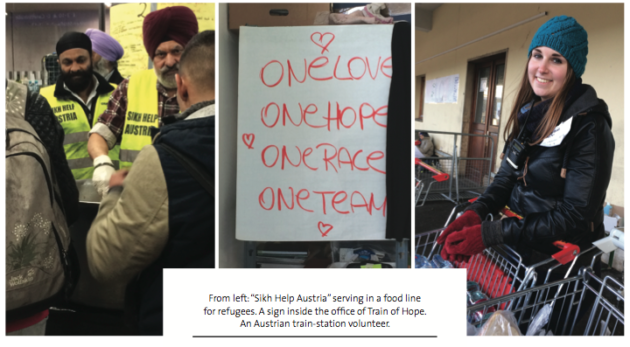

I have been tasked with dishing lentils (addas in Arabic) onto rice for all who are hungry (no one is turned away — food is available to refugees and the city’s poor alike), a blessing on this raw October day. On my left is a bearded man serving rice and proudly sporting a vest emblazoned with “Sikh Help Austria.” On my right is Stephania, the Austrian-born child of refugees from Communist Romania. When I hear this, I greet her with “Che face?” (“What’s up?” in Romanian) to her great delight, and as a reward she opens up and tells me that it has been difficult being a immigrant child growing up in Austria. “I am not a ‘clean’ Austrian,” she says, meaning that she is not pure Austrian, but the malaprop lingers in my mind uneasily. On the other hand, she is proud of the country that took in her parents in the early 1990s and it upsets her when Americans know her country only as the birthplace of Hitler, not Mozart.

The last time I was in the Sudbahnhof was in 1990, when I came to Vienna to write a series of articles about Russian Jewish refugees, whose first stop on their journey to the West was Vienna. From here, they were sent by train to Rome, where the United States processed their refugee applications. I remember coming to this station at nightfall and being loaded onto a train with hundreds of Jewish refugees. We rode all night through the Alps in locked cars, guarded by Austrian and then Italian troops. And although this was for their/our protection, it was a jarring experience for a sheltered reporter from the U.S.

In front of us today are other faces. I serve two women — not in burkas — from Afghanistan, a Kurd from Iraq, and countless Syrians. They have been in Vienna several days and don’t seem to be headed anywhere yet. Nor have new refugees arrived since Hungary closed yet another border on Saturday night. (Unlike the U.S., Hungary has borders with multiple countries.) As a result, the refugees are in camps on Austria’s southern frontier, unable to move without the seemingly slow cooperation of the Austrian national railway, which hasn’t yet been able to add trains. Later in the day, a concerned Caritas official will tell me that this is very bad — Caritas has only 2,500 beds on the border, but 8,500 in Vienna. At the moment refugees in the south far outnumber the available beds.

Once the lentils are gone, my usefulness dwindles and I get itchy to return to the Westbahnhof to work with Caritas. This dreary day is vastly brightened by the welcome I get at the door from Peter, who had put me to work yesterday. Remembering my name without a prompt, he squeals, “Roberta, you’re back!” This feels right, I think, and happily dive into more clothes-sorting until closing time.

Passing up the opportunity to go out with the boys (and I mean boys!) for a beer, I wearily walk home ruminating on my day. The face of Austria has changed for the better, I think. But then, I remember that there were always good Austrians, and that this is a place that cannot be so easily characterized. In 1938, before fleeing, my father hid the family’s art, silver, crystal and porcelain with an honest business associate; in 1946, after the war, he retrieved it all with nary a crack or chip in any of the fragile treasures. My one regret is that I was shortsighted in my youth and allowed my father to take to his grave the name of the Austrian family that helped us, and I will never be able to thank them.

These are the thoughts going through my head as I walk through my immigrant neighborhood in the bone-chilling rain. That and a combination of gratitude and worry. Grateful that I have a warm, cozy place to return to…and worry about how the refugees on the border are surviving this dangerously unpleasant weather. Hopefully, in the next few days, we will start to see their faces in Vienna, too.

Seeing the Individuals

I have spent the last two days busily sorting and distributing shoes at the shoe “shop” run by the all-volunteer Train of Hope refugee-service organization at the central train station. Hidden away deep inside an unheated tent that houses men’s, women’s and children’s clothing are shoes, lots of shoes. With the shortening of the days and the chill of the Austrian evenings, refugees certainly need warm jackets and sweaters, but the one thing people on the move need the most is a warm, comfortable pair of shoes.

Overnight, I have become a shoe expert — British sizes, European sizes, babies’ shoes, women’s shoes, the best shoes for little boys; you get the idea. I can look at a refugee, size him or her up by chatting in pigeon-Arabic/English and generally produce the right style and size.

Over two days, the shoes have all become a blur (full disclosure: being a would-be fashionista, I must admit that a few do remain stuck in my mind’s eye). But the last thing I want is for the people I’ve helped to run together in my head. So, I try to look each person in the eye and remember something about him or her. Here are some quick takes on a few of the many refugees dancing across my internal screen as I power down for the night….

Yesterday, a man came into the shoe shop, looking lost and dazed. I started chatting with him and learned that only four days earlier he had made the treacherous crossing from Turkey to Greece — only a four-hour boat ride, but the boats cannot hold their own against the angry waters. He told me with a catch in his throat that his family had arrived safely, but that he had sat helplessly watching as the rough seas washed into the boat, overcoming an infant, who died in his parent’s arms.

Tonight, another man came in carrying a six-month-old baby girl, who had neither booties, socks or shoes. She was barefoot and running a slight fever. We quickly found her some baby socks and applied them in layers. When we found her a pair of baby boots that were too big, he refused them — until we convinced him that she would grow. We watched this dawn on his face as he imagined a brighter future.

Earlier in the day, an extremely fashionable young man showed up with a great pair of shoes on, but he clearly wanted something different. I was fascinated by him. In this vast sea of tired and tossed humanity, he was quite the dandy. I approached him gingerly, eager to learn his story, but afraid I’d scare him off. Though most of the refugees are Syrians, there are also Iraqis, Afghanis, and Persians. He was a Palestinian from Jerusalem who had travelled overland through Lebanon to Turkey to Greece, eventually reaching Austria, where he intended to seek asylum. I made short business of telling him I was Jewish. He grinned widely telling me that his best friend in Lebanon was Jewish (apparently this line knows no borders!). Since most Palestinians know some Hebrew, I asked him if he did. “Tuh,” he clicked with his tongue (Middle Eastern for “no”). “I only know ‘shalom’.”

One woman stood out for her brilliant command of English. She took her fluency completely for granted, even though few around could match her. Plucky and independent, and 32 years old, she explained to me that she had lost her husband before Syria conflagrated, leaving her with three very young children. She had been on the road with them for 28 days and was headed this evening to Hamburg and onward to Copenhagen. “I am bone tired, but it is worth it for my children’s future,” she told me with clear, strong eyes.

My favorite was a kid with low-slung jeans and an attitude who started rummaging through the women’s shoes. I had already explained a million times to a million people that the women’s shoes were on the left and the men’s shoes straight ahead. I tried again and the kid said “I know,” and continued looking for women’s gym shoes. Undaunted, I kept steering him to the men’s shoes. He finally got sufficiently annoyed and removed his cap as shoulder-length hair tumbled out. He turned out to be a she. She was the first real tomboy I’d ever seen in the Arab world.

The point here is that the people I’ve met are different from the rest of us only by experience — not by nature. They are fleeing repression and war in lands that have been torn apart by ethnic hatred — looking for a brighter future for themselves and their children. And I have seen lots and lots of children, most of them well-behaved. In fact, considering what these people have been through, each and every one of them is behaving far better than I ever would were I unfortunate enough to be in their situation.

As one of the Israeli brothers Cohen who own/run a Jewish family restaurant (they announce this as they seat you) in the Hauptbahnhof, said to me over dinner tonight: “In a month of serving refugees, we have not had one disturbance of any kind. And no matter what they’ve been through, they always seem to have a smile for us.”

Back in the shoe “shop” after dinner, bedlam reigns: the size 40s are mixed in with the 38s; I find the right half of a pair three boxes away from its mate. Taking a page out of the Austrian playbook, I quickly try to make order from chaos. I have been doing this repetitive motion all day and it’s starting to feel Sisyphean. But I realize that I don’t have the luxury of thinking that way for fear it might infect my views of the refugees themselves, who are coming in a steady stream. As soon as one group is moved out another fills the vacuum. But they are not objects, they are not shoes, they are not stones we roll uphill. They are humans whose yearnings for a peaceful life are the same as our own. Sisyphus never quit, and they, too, deserve our best efforts.

Erring on the Side of Humanity

Last Saturday, most coincidentally and precisely timed to my arrival in Vienna, the right-wing powers in Budapest succeeded in closing the Hungarian border with Croatia. The results have been to halt almost entirely the flow of refugees into Vienna. Just as water always seeks its own level, the refugees shifted course and started traipsing through Slovenia towards Austria’s southernmost border. By all reports, tens of thousands have amassed there — stranded, their destinies out of their control. Today the dam broke and once again waves of humanity started pouring into Vienna.

Coming to Vienna is not necessarily good for the refugees — since most of them are heading north to Germany and Scandinavia. Vienna is not on a direct line from their starting point of Graz in the south to Salzburg, the gateway to the north. But though a detour, a way-station in Vienna is not necessarily a bad thing, either. Basically anything is better than the camps on the border, where there is standing water from the never-ending, bone-chilling rain.

The refugees began arriving by bus to the train station this afternoon at about 2:30. Initially visible a quarter mile down the tracks, they appeared spectral, wearily marching forward in single formation. As they got closer, individuals and family units gradually took shape. Within minutes, hundreds of hungry, worn-down refugees were upon us and it was our job to feed them. The menu varied by the moment, but there were always bananas and apples, bread, pretzels, cookies, and water. At times there were dates, nuts, and hot vegetable stew with rice, courtesy of two Austrian women who had cooked up a storm at home and brought a feast to serve. It smelled divine, and for a good half hour the refugees were drunk on the aroma and full bellies.

But passing out the food became a sobering and painful experience when we realized we didn’t have enough to go around. I made it my business to make sure that all the children had cookies (I actually had to wrest packages from the hands of some big guys equally intent on them), and that all the babies had formula. I’m not sure I’ve ever been around people who have known such privation. I spoke with one woman who left Iran 21 days ago, and she told me that they were forced to walk 60 kilometers across Croatia to the Austrian border. Freezing on the train platform after only a couple of hours outdoors, I felt their pain even more acutely.

Today, I realized that one of the hardest aspects of being a refugee is to live a life totally free of autonomy. Every movement, every meal, every smoke, every pit stop is ordained by others. The last independent, self-determining move that any of them may have taken was the decision to leave everything behind, and to pack their lives into several large plastic bags for the fickle promise of a future.

I am hard-pressed to begin to understand what they have endured thus far on their journey — and that journey has only just begun. The people I have met this week abandoned their former homes and livelihoods only three to four weeks ago. This is unimaginable to me — one month ago, I was sailing on Lake Ontario, not taking an irrevocable step into

the unknown!

There has been much talk in the media about ISIS sending sleeper cells among the waves of refugees. Yes, the majority of refugees I have seen are young men — starving, weary, beaten-down young men, who have had their youth stolen from them by war and conflict. Surely, there are better, easier ways to infiltrate the West than posing as a refugee. No human being willingly chooses to give up all that is precious unless there is simply no other option. It is impossible to know this until you look into the eyes of those who have lost everything. There are no assurances, but bearing witness to this vast wave of migration has convinced me that I am much more comfortable erring on the side of humanity.

A Merciful Forgetfulness

My trip ended as it had started — with me sorting clothes for distribution to the refugees arriving in Vienna after weeks on the road. The sorting served as suitable bookends to my week in Vienna, crossroads for the four million refugees bearing down on Europe in their flight from Syria, Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan. In between, I had distributed clothes and food, a more glamorous, and also far more stressful exposure to Europe’s biggest refugee crisis since World War II.

But, after two days greeting new arrivals on the tracks, I decided I simply couldn’t bear watching grown men shove women and children aside to grab food. It was too demeaning for them to have someone bear witness, so I opted for the gentler task of clothes sorting. And the quantities of clothing that needed to be divided into gender and size was seemingly infinite. As infinite as the good will that kept the Caritas donations door open and active 12 hours a day, seven days a week. No matter what time I strolled past, there were cars pulling up, packed to the roof with another Austrian family’s cast-aside treasures. It was enough to restore one’s faith in this Central European country with a troubled history.

During my week here, I generally had to fight to get a volunteer assignment — today, for instance, a Sunday, there were dozens of young Austrians volunteering for every form of menial labor — shlepping food and water up to the tracks; preparing bags of bread, nuts and dates in the kitchen; receiving donations; performing an initial sort, and then a secondary sort. There was a sea of volunteers ministering to a sea of the displaced — two bodies crashing up against each other, impacting one another.

If only, I kept thinking…. If only the Austrians had stood their ground against the invading Germans the way they were thankfully extended themselves for this group. Where were today’s kind Austrians when my father was forced to flee in the dead of night nearly 80 years ago? How different his life and those of thousands of others would have been had Austria behaved differently then. I like to think of him watching them now, and taking some measure of comfort from their actions. What exactly would he think — my father, who traveled the world but could bring himself to return here only once in a lifetime that lasted more than 50 years after his expulsion? And what would he think of my frequent, searching trips here, especially this one to work with a new refugee population?

The situation here is ephemeral. It changes from one day to the next. People arrive, are taken care of, and leave. It is as temporary as the shoes they wear — they can mark their journey by what’s on their feet. They left Syria — or Afghanistan or Persia — with one pair of shoes, and got replacements at various stations along the way, their footwear as ephemeral as the relationships they build in flight.

The other day I spent an hour with an unforgettable man in the “shoe store” at the Hauptbahnhof, as he searched and searched for a pair of boots to ward off winter’s insidious cold. Try as I might, I could not produce the perfect pair. As he got more and more frustrated, I told him to come back the next day when there would be another batch of boots. Today, I was so excited when I saw him at the clothing dispensary at the Westbahnof. I ran over to him and joked about “boots,” sure he would remember me. All I got back was an empty stare and a request for size 43 boots.

I must admit, I was a bit crestfallen to have been so easily forgotten when I will never forget his resilient spirit, but scolded myself afterwards. It is good that the nature of crisis is ephemeral. It is good that people move on, that relationships are only temporary, that life eventually finds permanence not here on the road. It is especially good that for most refugees this rugged migration will eventually be a distant memory as new opportunities open in new lands — especially for the children.

I know it was so for my father, who never spoke of his flight. After years of displacement, he finally settled into America, met and married my mother, got an education, established a career and had a daughter. I was never sure if he buried the experience by sheer dint of the steel will that got him out in the first place, or if he easily forgot his years in flight. I wonder if he ever thought of those who helped him along the way? I wonder if they had as much impact on him as he had on them? I suspect not. I suspect that the ephemeral nature of the journey is the saving grace that makes it bearable. It is nature’s way of preserving us from losing ourselves so that we can continue to move forward.

I came here to help, and help I did. I leave here knowing that the refugees have been treated well along their way to journey’s end. I will get on the plane tomorrow, warmed by the kindness I saw and the knowledge that Vienna seems to have changed since 1938. I will get on the plane, enriched by the lives I touched and which touched mine. With no regrets and with the comfort that this nightmare of theirs is transitory and that once it is over, the gratitude is contagious.

A retired Jewish community professional who worked at Hadassah and HIAS, Roberta Elliott volunteers, particularly with refugees. She next plans to provide humanitarian services on the Mexican border and help refugees in Greece arriving in boats from Turkey. Follow her at robertaelliottwordpress.wordpress.com.