From the Editor

I wrote a very different version of this editorial many weeks ago. Then, my anxieties (yours too, perhaps) were fixed on elections in the U.S. and Israel, the trial of Harvey Weinstein, the rising and ugly challenges to our reproductive freedoms.

That was then.

Now, other questions about survival are our urgent preoccupation.

Pray that the lessons this pandemic is teaching us—about shared social responsibility and empathy and appreciation for resilience—will remain with us as we shape a reality dramatically different from what we’d anticipated for the year 2020and beyond. In the weeks since Lilith’s winter issue, we have all entered a very narrow place, physically and emotionally. In the midst of this crisis, Lilith, like so many of you, continues moving forward, though the path and pace have altered. The staff, working remotely, join for a daily lunch meeting by video, sharing ideas, distributing the work load, acknowledging the presence of children, pets, and uncertain video connections. Lilith has a long, strong history of creating community—in print, through our blog, in the magazine’s robust salons, and with the interns and emerging writers we continue to nurture and engage, albeit at a safe distance now. And Lilith is continuing to strengthen connections with our readers by creating on-line video programming for pleasure, learning and support at this time of estrangement from our old normal.

I’ve been thinking of my maternal grandmother—my Baba— as I try to imagine what it felt like to be caught in the influenza pandemic of 1918. She saved the family from contagion, so my mother said, by hanging sheets soaked in bleach in the doorways of their house. Who knows what really helped? But in her stolid practicality, I see a precursor to the behaviors of so many of my friends and colleagues right now, women forced to make inventive and hard decisions we’ve mostly not faced before, as we move from a promise of abundance to a reality of scarcity.

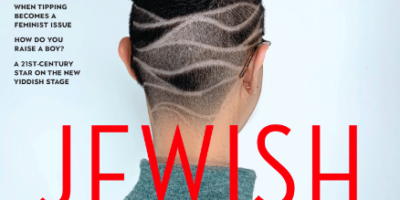

Much of this spring issue was prepared before the virus struck. In those long-ago February days before the extent of the coronavirus crisis was fully upon us, I was measuring change over time using this issue’s series of first-person ruminations on hair, which in my mind would mark a shift from 25 years ago when Lilith last tackled the subject in a cover story. Entitled “Jewish Hair!” that special section in spring 1995 was described as “20 pages on Ethnicity, Gender, Power, Sex, Shame, Secrets, Independence, Laws, Identity, Sensuality, Courage.” (Hair, like money and food, is a topic uni-versal in its magnetic ability to draw out people’s personal experiences.)

This time around, Lilith’s editors predicted we’d perhaps see stories from trans people about hair as a liberating indicator of gender identity, or from women using their locks as a colorful

index to fashion trends. Maybe a guilty confession that covering graying middle-aged hair is “bad hair politics.” But no; we got one of the above. What you will read here surprised us. Hair as a valuable intergenerational connector, with unrecognized potential to express tenderness. The mores that dictate social interactions in a hair salon. Acceptance of body hair. Racial prejudice that punishes Black hairstyles. And, movingly, the brave and powerful words of an 11-year-old girl, losing her hair from the ravages of her cancer treatment.

A subject that seemed radical more than two decades ago has with Lilith’s coverage matured into a growing respect for the diverse ways we mark our identities and our emotions. A similar tone—let’s name it mutuality—appears in other sections of this issue. Raising misogyny-free boys today is a responsibility not only of their [feminist] parents, but is also shared by a society

trying to shift expectations so that all children are unshackled from constricting gender norms. And in Lilith’s section on wages, it’s clear that addressing poverty and inequity can’t fall only to calls for tzedakah or tikkun olam.

This crisis has shown us that we are more dependent on many different forms of labor than we may previously have realized, and we are called to treat all workers with the highest ethics—as Jews, as women, as vulnerable, interwoven human beings on this planet. I hope we’re all able to keep that sense of mutuality in mind as we eventually step into a world forever changed.

In our eerie, shared present moment, I hope you’re able to stay safe, and as comfortable as possible.

Susan Weidman Schneider

Editor in Chief

susanws@lilith.org