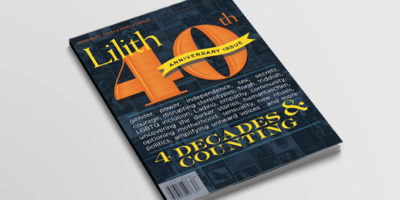

from “Coming of Age as Iraqi Jew in California”

When Jewish always meant Ashkenazi... [Spring 1996]

Art: Colleen M

My name is Loolwa Khazzoom. I was born into an Orthodox Jewish family, with an Iraqi father and an American mother. The first priority in my parents’ life was giving my sister and me a solid religious education and Jewish identity.

My day school in San Francisco, however, was solidly Ashkenazi. My teachers were virulent about equating the word “Jewish” only with traditions that had European roots. I was repeatedly ridiculed on account of my family’s Iraqi customs…. The rabbi “read” to us from the Bible the following “verse”: “It is against Jewish law to pray from a Sephardic prayer book.”

From that day on, my primary Jewish education came from home, spending every Shabbat learning Middle Eastern prayers, religious songs, holy day traditions and rabbinical teachings. Of course, I continued learning the Ashkenazi traditions by default: Outside of my home, in every “Jewish” synagogue, camp, community organization and community publication, “Jewish” still meant “Ashkenazi.”

As a pre-teen, I could sing the Shabbat and weekday evening prayers in the traditional Iraqi tunes; I knew dozens of Iraqi Shabbat and holy day songs by heart, and I could sing a good portion of the Haggadah in the Iraqi melodies—both in Hebrew and Judeo-Arabic (the traditional language of many Middle Eastern Jews).

It was rare for a child my age to know all these prayers. It was even more rare that I could sing with the distinct Iraqi pronunciation of every word. Because I was a girl, however, I was not allowed to lead any part of the main prayers [in our Iraqi synagogue]. After considerable fuss, I was allowed to lead parts of the supplementary prayers, the reason being that those did not “really count.”

I remember my pain when, once in a blue moon, a boy would come into the synagogue. Even if he knew nothing, if he stumbled and sputtered his way through the prayers, he would be instructed to lead instead of me, and I would be shunted to the side. Once, just as I was climbing the steps to the bimah [altar] to lead some prayers, a boy entered the synagogue. One of the congregants came and literally pulled me off the bimah. Several men shoved a prayer book in the boy’s hand, and there was a communal sigh of relief. It was a terrible experience for me.

My father kept saying it was not fair the way they treated girls; yet we kept coming to the synagogue. We had no revolution against the system, and we did not walk out on it. Accordingly, I learned that though this treatment was not fair, it was acceptable. And I learned to accept it.

The day I turned 12 and a half—bath mouswa age—I was banished to the women’s section….Coming of age as a woman is not treated as an honor but as a punishment.

Vocally joining in the prayers was my last shred of connection to the congregation; I sat in the front row of the women’s section, heartily singing along. One day, the rabbi decided that I was not to sing audibly, for I was violating the law of kol- isha, forbidding a woman’s lone voice from being heard by men.

My father and I left the synagogue that Shabbat, and I spent the next two years going to Ashkenazi synagogues. I neither participated in those services nor cared to, as those traditions meant nothing to me.

When I was 15, I stopped attending services altogether.