Diane Arbus Through a Different Lens

Diane in Central Park, circa 1939. This picture was owned by her brother Howard throughout his life and is likely the image of Diane that he carried in his Bristol Beaufighter when he flew bombing missions during World War II. Courtesy of Alexander Nemerov.

Born in New York City in 1923, Diane Arbus (née Nemerov) was a kind of Jewish American princess. Her mother, Gertrude, was heiress to a department store fortune, and Diane grew up on both Park Avenue and later, at the San Remo, on Central Park West, surrounded by the trappings of luxury: nannies, a French governess, cooks, maids and a chauffeur. Yet even as a young girl, she was uncomfortable with her family’s wealth, and eventually forged a very different path for herself than the one her mother might have envisioned for her.

She attended the Fieldston School for Ethical Culture, and was recognized as a gifted student (“far more brilliant” than her brother, poet Howard Nemerov), and a sexually precocious young woman. At 18, she married Allan Arbus, whom she’d been seeing for five years; she met him, an employee at the family store, when she was 13. Working with Allan, Diane, who had already shown talent as a painter, started out in advertising and fashion photography. The pair became a quite successful team, with work appearing regularly in Vogue and Glamour.

Although known by reputation as a photographer of sideshow freaks, transvestites and other marginal characters, Diane took many more pictures of conventional women and children. She had a two-part process. First she charmed her subjects, then she lowered her head to the viewfinder and captured them.

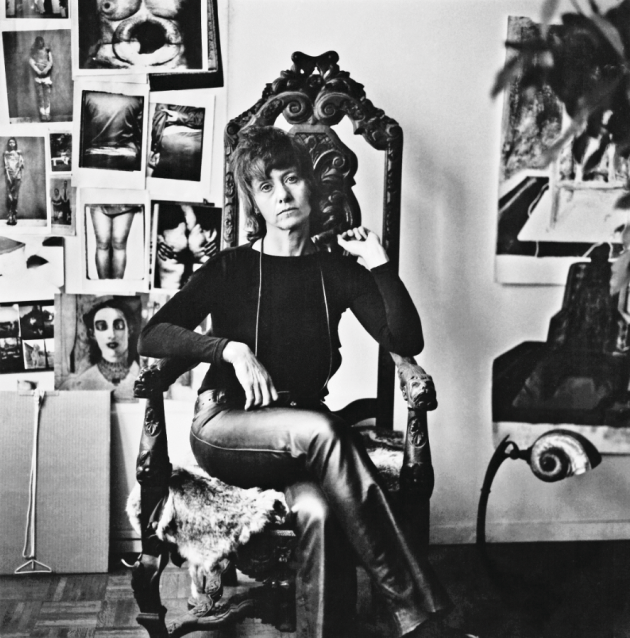

©Tod Papageorge.

In the late 1950s, Diane began to focus on photography of a very different kind. Camera in hand, she visited seedy hotels, public parks, and the public morgue, drawn to outsiders, those on the fringes whose social acceptance was marginal — or non-existent. Dwarfs, transgender people, nudists, circus and burlesque performers — these were her subject and her raw material, all of them embraced, and graced, by her wildly curious but never judgmental lens. The titles of her best-known photos are, by now, iconic, “Jewish giant at home with his parents in the Bronx, 1970.” “Girls with a cigar in Washington Square Park, N.Y.C. 1965.” “Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C. 1962.” Rather than feeling superior to her subjects, she felt a kinship with them that is visible in her oddly tender photographic rendering.

Unlike some other photographers of her era who often preferred to photograph their subjects surreptitiously, Arbus, according to a new, unauthorized biography by Arthur Lubow, Diane Arbus: Portrait of a Photographer (HarperCollins, $35), wanted very much to be seen by those she was photographing. It appears that she wanted to be known, in some way at least, by the person in front of her camera. Lubow says, “She knew why her subjects invited her photography. ‘I think you’re paying a kind of attention to them that nobody pays, you know, that their own mother wouldn’t pay’, she explained. ‘I want to hear everything they have to tell me, and I’ll tell them too’.”

By the mid-1960s, Diane had become a well-regarded photographer, and her work was included in shows at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, among other venues. But while her career flourished, her personal life did not. Her marriage to Allan ended in 1969 and she struggled with depression. On July 26, 1971, she committed suicide in her New York City apartment.

In 1971, Diane was gaunt and depressed. She lamented that her work no longer gave her anything back. In her Westbeth apartment, she posted photographs that depicted people with deformities and victims of horrific violence. © Eva Rubinstein.

Secrets were an important part of Diane Arbus’s life and her relationships — not the least of which was the one with her brother, as Lubow makes clear rather abruptly. “Diane was a great hoarder of secrets, persistently extracting those of others, distributing her own strategically. In the last two years of her life, she paid weekly visits to a psychiatrist in an effort to cope with her depression. She revealed in those sessions that the sexual relationship with Howard that began in adolescence had never ended. She said that she last went to bed with him when he visited New York in July 1971. That was only a couple of weeks before her death.”

More than 40 years later, her work remains a subject of intense fascination and interest, with several biographers exploring her art and its inspiration. Her life was the basis of the 2006 film “Fur,” starring Nicole Kidman. And in July a major exhibition of works from her early years opens at the Met Breuer in New York.

Yona Zeldis McDonough is Lilith’s fiction editor and the author of seven novels. Her most recent is The House on Primrose Pond.