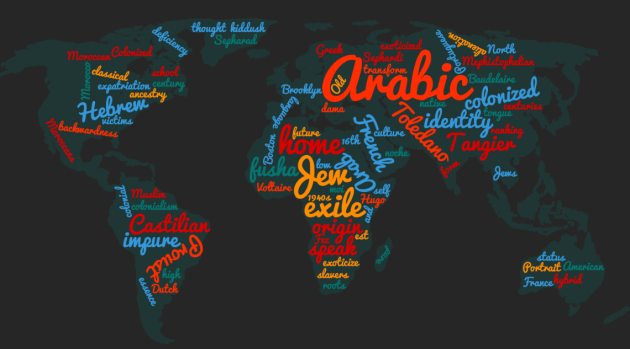

Choosing Which Language to Live In

Roiled by her culture's hidden messages of colonialism, patriotism, alienation and intimacy, a Moroccan Jew comes to terms — in Connecticut.

“I feel closer to an Arab from Morocco than to a Jew from Brooklyn or Boston.”

“I feel closer to an Arab from Morocco than to a Jew from Brooklyn or Boston.”

My mother is a Moroccan Jew, born and bred in Tangier, where she also spent most of her life. Her words rang clear as I asked her to leave Morocco for the United States, where I have lived for 18 years. Although she no longer has any relatives in Morocco, I doubted she would ever settle in the manicured and uneventful Connecticut suburb where I live with my family.

Being Sephardi means something powerful to my mother: a kinship of spirit rooted in the Mediterranean, a shared grammar of tastes, flavors, sounds and idioms, a vocabulary of cultural and regional affinities threaded together bit by bit through the centuries. For her it is a complex closeness with Arab and Spanish cultures. It is less so for me.

I used to envy her the emotional clarity about her identity I lack. Morocco is her country. I, on the other hand, left when I was 18 to study in France, and I never came back. She grew up in a thriving Jewish community in the 1940s, I in a waning one in the 1970s. I felt in exile before I had even left. It was a time when almost all Jews had left their homes in Arab countries for France, Spain or Venezuela, incited by subtle economic pressures to depart.

For years, I looked towards France, where I went to pursue my literary studies. My touchstone references were Voltaire, Hugo, Baudelaire. I wrote a dissertation on Marcel Proust and became a French teacher, effortlessly passing for French. Although I am a descendant of the well-regarded Toledano family (Rabbi Daniel Toledano was a sage who lived in Fez in the 16th-century after his family was expelled from Spain in 1492), I viewed my Castilian ancestry as a distant origin, an appendix to myself. Even though colonial times were long bygone, I, a native of Tangier, was a pure product of French education, and my alienation ran so deep that I looked at my non-Gallic being with wariness. From Albert Memmi’s brilliant analysis of the colonized self, I knew that “Portrait of the Colonized,” c’est moi!

Like Memmi — a Jew of Tunisian origins — I spoke multiple languages, but this was no mere useful multilingualism. It was confusing and alienating. Each language came with a price. It was a Mephistophelian bargain. French — the tongue of thought and flight — ranked high on the list. By contrast, Arabic was low, the locus of backwardness and deficiency. We did not speak it at home, though I later learned it at school in its “high” form — “Fusha,” or classical Arabic — versus the “Darija” spoken by most Moroccans. Instead, at home we used Spanish, but that too came with strings attached. There was “high” Spanish, with its soft Castilian inflections, and our own hybrid form, Haketia, which was the vernacular of Moroccan Jews from the North, and a byproduct of another exile, 1492. Preserved through the centuries like a jar of marmalade, it consists of Old Spanish, with accretions from Hebrew and Arabic.

As a result, by the age of 18 I had created a tacit hierarchy of languages, with unspoken labels assigned to each such as “high” and “low,” “pure” and “impure.” Like Jekyll and Hyde, I took on different personalities depending on which language I spoke. It was a disastrous split in personality. If one considers Sephardism as an intrinsic form of expatriation, then exile made up the very structures of my psyche from birth, so I was bereft of a mother tongue from the outset.

Language is a condition of national identity. But in my case, a single reality took on multiple translations as through a distorting mirror. One object came burdened with manifold designations. It was like being in Plato’s cave, tirelessly groping for reality’s true essence. No definition was fixed, and unity irretrievably lost.

Was colonialism to blame? Partly, but hold the vagaries of history responsible too, with its victors and victims, and the special status of Tangier as a cosmopolitan center and as an international zone until Morocco became independent in 1956. This had made me, and other Moroccan Jews of my generation, the last links in an evanescent community, a chronological error in time and space.

As a result, I forsook Sepharad.

My guardedness against things Sephardi was flagrantly exposed during my wedding to an American Jew in Tangier in 2005, the first Jewish nuptials there in 25 years. We had a traditional Sephardi ceremony called in Northern Morocco “noche de Berberisca.” The place was the garden of the house where I grew up, with its cornucopia of gladioli, hibiscus trees, plumbago and bougainvilleas. My parents’ home — now razed and in its stead an unremarkable building of disharmonious proportions — was located in what was then known as the Parc Brooks, an area of Tangier developed by my grandfather in the 1950s.

Our wedding took place on a balmy June night, the air was bursting with the fragrances of early summer, jasmine and lemon trees intermingling with a flower I knew by its evocative Spanish name, dama de noche (lady of the night), or night jasmine, because it smells only from dusk to dawn.

As required by tradition, I wore an elaborate eight-piece costume, the “traje de Berberisca,” all deep velvets and embroidered gold threads, whose origin can be traced back to medieval Spain. My mother had been collecting the parts for over 50 years, painstakingly assembling ancient rags of dazzling fabric found in dusty bazaars. It is a splendid gown (mine was deep amethyst), with a symbolic meaning for each of its parts, and donning it should have made me content, connected to my past, conversant with history. Instead, I was ill at ease and self-conscious in it, an impostor. Feeling exoticized, I wore it grudgingly.

I was having a destination wedding in my own land.

When the moment came for me to come down from the room where I had been expertly dressed in my cumbersome attire by the woman responsible for preparing brides, my uncles came to escort me. They sang the Shojanet Ba Sade, the bridal hymn also chanted in the Sephardi rite on Simhat Torah to honor the Torah as metaphorical bride. Instead of pacing slowly with the procession, I rushed down. I just wanted to get it over with.

Then, a peculiar and unorthodox thing happened.

As I walked out into the gardens, our Muslim friends broke into song in Arabic, reciting the verses used in Muslim weddings: Slah u Slam ‘aalik ha rasul Allah, Illah ya Sidna Mohammed, Allah maa ja el ‘Aali (May prayer and peace be sent to you from God. Our lord Sidna Mohammed has arrived from the heavens). This moment provided an instant of unusual intensity, because it belonged perhaps to another era, the time of convivencia between Jews and Muslims in the old 14th-century Sepharad, a reenacted and updated hour of harmony between rival religions. But, alas, I missed the point, just like Fabrice del Dongo in the fog of the Napoleonic wars.

My thoughts were turned instead towards the civil ceremony my husband and I had enacted a month prior in New York — primarily to get our paperwork in order, since I was in possession of a Moroccan passport. A Justice of the Peace came to our apartment and married us in a swift, purposeful ceremony. He was of Irish descent, and the intricacies of my heritage were lost on him, which was of no consequence to me then. The ceremony was clean, and simple, and from that moment on I had felt the binding vow that proclaimed us husband and wife.

I have now been married for over 10 years, and I look back at our Berberisca night with lingering regret, because I failed to embrace a meaningful tradition. I had just been a spectator all along.

Change, in the form of reappraisal, came to me slowly and unannounced. In America, I encountered small alienations daily. I often felt “Jewishness” — predominantly Ashkenazi — was a different planet. Language, yet again, offered me ample opportunities for loss of meaning and misunderstanding. For example, the final words of the Kiddush, the blessing of the wine on the Sabbath, are pronounced: bore peri haguefen with an “é” sound by Sephardim, but haguofen by Ashkenazim, a remnant of Yiddish, which Sephardim do not speak. A difference in a single letter encapsulated diverging universes. I wasn’t going to “snoga,” my Judeo-Spanish for synagogue, but to “shul,” the word in Yiddish unfamiliar to me. In America, there is meager collective imagination left to Sephardism, often ignored — or simply terra incognita, and thus viewed as lesser, simply a foil to the Ashkenazi experience. The rites, traditions and melodies were so different, I felt once again lost. I still could not find my place.

A decisive blow came last year, however, when I read in the Forward that a new law in Spain granted citizenship to those of proven Sephardi lineage. The reporter, an American Jew of Sephardi ancestry, had travelled back to Spain in search of his family’s roots. He concluded his somewhat erratic travelogue with strange advice, proclaiming it useless to look back at our past, because it is only our present actions and our future that matter. I was baffled: is rediscovering and reappraising our past, our roots and our history, a disregard for our future? It seemed rather the opposite: our past propels us forward because it enriches and densifies who we are.

So I started reading about Sephardi culture. Ammiel Alcalay’s book After Jews and Arabs, published in 1990, provided illuminating background, with material often disregarded by history, or dismissed by Israeli wariness for things Sephardi. I became fascinated by the world of the Levant this book described, of a Jewish and Arab symbiosis so implausible today, of Jewish and Muslim poets versed in Spanish, Arabic, Latin, Hebrew, Portuguese, Dutch and Greek. I drew parallels to the Mitteleuropa of the early 20th century with its Babelism and vibrant intellectual life. I read Judeo-Spanish Romances, and found rich literary forms that differed from the Western canons. I’m still unsure how I will make all this a part of my American life, or how I’ll transmit it to my American children, but I’m now intrigued by aspects of a culture I had never fully seen as my own. To paraphrase Simone de Beauvoir about womanhood, one is not born, but rather becomes Sephardi. At least, in my case, it has been so.

Tellingly, the final transformation occurred as I was also becoming more American. Language was once again the vessel holding my crisis. But it now took on a redemptive power. English, which I acquired late in my twenties, was slowly growing to be mine. It became my language of intimacy and affection with my husband and children. I began writing in English. Words came without the burden of history or power dynamics between nations, or generations. They were a clean slate — my own — like a reset button. English was neutral, equitable, open-minded. No high and low, no pitting of heart and brain against each other. In English, I can look back at my roots with a composed heart.

Through English, I felt I had conquered the New World, where I could be whomever I chose. It was the great equalizer and the artful revealer of my own origins, and it was liberating. I was no longer anxious about who I was. I even acquired a U.S. passport. Ironically, becoming more American had allowed me to become more Sephardi.

Yaëlle Azagury is a book and art critic. Her essays and reviews have appeared in the Jerusalem Post, the New York Times Book Review and other publications.