Big Mouth, Big Ideas

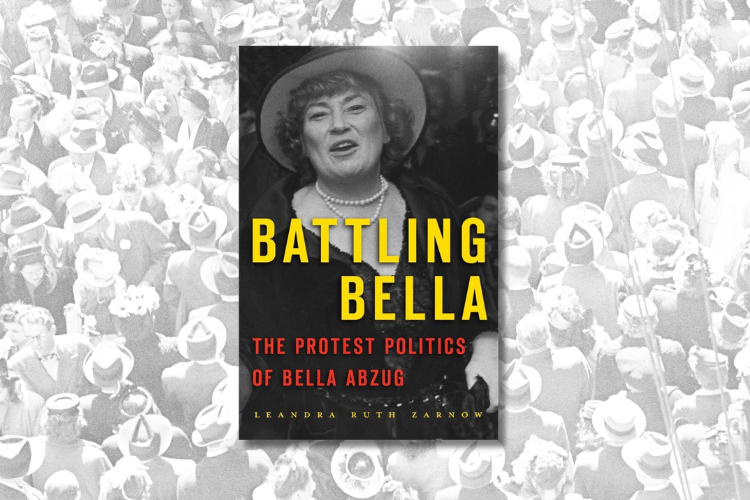

Battling Bella: The Protest Politics of Bella Abzug by Leandra Ruth Zarnow (Harvard University Press, $35) is a comprehensive, sympathetic—but never hagiographic—biography of the first woman to serve as a whip in the U.S. House of Representatives, where she represented New Yorkers from 1971–1977. While the book does not shy away from highlighting Abzug’s harsh treatment of her staff, it also notes her unflinching demand for gender parity in hiring practices of political campaigns.

In addition to noting her contributions to feminist politics and movements, Zarnow also vividly describes Bella’s formidable persona (including her iconic hats and use of the phrase “Abzuglutely.”) We glimpse Abzug’s personal life through her decision to cross gender boundaries and say kaddish for her father—in 1934, when she was still a teenager—and her devastation later in life over her husband’s death.

The book deliberately situates Abzug as “a participant in the American Left,” and frequently refers to her push for social democratic policies both as an activist and as an elected congresswoman. Abzug won office in New York City as part of a wave of New Politics Democrats who were seeking to realign the Democratic Party in a more progressive direction.

The successes and failures of New Politics Democrats have defined the political landscape in the intervening years, and it is impossible when reading this biography not to hear echoes of our current political moment through its pages.

Zarnow makes this most explicit when she notes the Democratic Party’s introduction of “unelected superdelegates with voting powers in 1984 to keep insolent challenges… in check.” In effect, these unelected superdelegates were meant to curtail the more radical candidates and policies the New Politics coalition might bring up for a vote on the convention floor (e.g. their passage of a platform plank in 1980 which called for Medicaid funding of abortion). As the author mentions, the role of unelected superdelegates again caused controversy amongst a new crop of reformers in the 2016 election and was only partially reformed as a result in 2018. As the 2020 Democratic Party convention approaches, the structural impediment used to stop Abzug and others from pushing feminist politics still partially remains in place.

While it can be ahistorical to draw oo many one-to-one parallels from the past to the present, I think it is worth highlighting a few further similarities. The cadre of New Politics Democrats who were elected to Congress in the late 60s and early 70s is evocative of the “Squad” of insurgent Democratic congresswomen who won office in 2018, as is the sense of crisis motivating them. New Politics Democrats urgently sought to end the Vietnam War and avoid nuclear Armageddon with a similar fervor to how current organizers are seeking to stave off a coming climate apocalypse. The campaign calling for Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (NY–14) to have a committee seat on Ways and Means mirrors both Abzug’s campaign to be on the Armed Services Committee in 1971 and Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm’s campaign to change her appointment away from the Agriculture Committee in 1969. Likewise, many of the same smears thrown at Abzug are similar to attacks currently leveled by the right. Particularly startling to me were the eerie parallels to the way in which attacks questioning the legitimacy of Abzug’s Jewishness parallel the smears leveled against many millennial leftwing Jewish activists, despite the divergent positions on Zionism between Abzug and many of the activists of my generation who are similarly attacked.

The 1960s and 1970s are not the 2010s and 2020s, and Zarnow effectively relays the climate and various political currents to her readership. The author advocates for re-evaluating the 1970s “not as an era of limits but as an imaginative, expansive” period. While there may be elements to this appeal worth considering, it is nevertheless inescapable that the ultimate inability of the New Politics Democrats to win a governing majority in the 1970s led away from social democracy to the consolidation of power in a neoliberal order. After losing her Senate bid in 1976, Abzug would never again return to elected office, though she had served as a Congresswoman for three terms.

The question facing those of us who share a similar vision of the world is whether our movement can avoid the same end. While Battling Bella does not provide clear answers to this question, it does provide a thorough depiction of one of the most iconic figures of the New Politics Democrats. By studying the past upon which our present is built, we can hopefully steer the course to a better future.

Amelia Dornbush works for a union in Michigan. She has previously written for Lilith and Democratic Left.