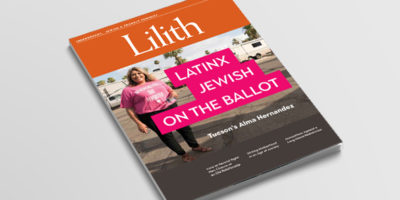

Arizona’s Jewish Latinx Candidate Shakes Things Up

On the road with Alma Hernandez and her political family.

Alma Hernandez, a first-generation Mexican-American Jewish candidate for Arizona’s state legislature, earned a spot on the November ballot in a hotly-contested August primary, part of a wave of young female candidates who, in their primary victories, have thrilled prognosticators and upset the political order. With a master’s degree in public health and a deep familiarity with the woes of her Tucson community, at 25 she’s one of the youngest candidates in the country. Yet she is politically seasoned; active in campaigns as a volunteer for 11 years, she and her two siblings even made a splash as a trio: all serving as official Arizona delegates for Hillary Clinton at the 2016 Democratic convention.

Hernandez’s local race presents a fascinating microcosm of the fraught responses a progressive, Jewish, female, pro-Israel candidate elicits. Accompanying Hernandez as she canvassed neighborhoods prior to the August primary meant appreciating how her devoted team of family members and friends reach out beyond those who consistently vote Democratic to make her case to independent voters who might swing to the Dems.

“Since the age of 14, I’ve been helping Democrats get elected here, and I decided to run for office because I feel that my community for far too long has been underrepresented and ignored,” she told Lilith. “In a state where Hispanics and Latinos are the majority but still the ‘minorities’, I felt that it was time for the voice of my community to be that of the people who have actually lived here and grown up here and know the issues.

“The majority of the people in my community come from single parent households,” she said, speaking of a district that includes wealthy university neighborhoods along with trailer parks and the Pascua Yaqui Tribe Reservation. (Yaqui tribal leader Sally Ann Gonzales, running for re-election as an Arizona state representative, often campaigns alongside Hernandez.)

“There’s a lot of poverty. We have high unemployment rates.” Concerns about health care and its attendant expenses are high on this list for Hernandez. Plus, “the funding for education is always severely cut in our districts.”

Hernandez knows the anguish many in her district suffer. In her campaign radio ad, she described how, at 14, after being “brutally attacked” at school by white girls, she was exposed to the criminal justice system, where she saw first hand “how the school-to-prison pipeline is rigged against people of color and those without means.” She had fought back against her older attackers, whose assault left her with permanent injuries, yet she was the only one the school police arrested. “I feel like the dignity and innocence of my youth and teen years were stripped away from me.

“I went from being an honor student to a criminal, warned by a prison guard that I’d be there [in jail] a long time. Nothing will change what that experience did to me. If it weren’t for the support team I had at home—my parents got me out later that night—I wouldn’t be where I am. I was able to not be a statistic like they wanted me to be to be. Instead, I wanted to make sure I understood statistics, and I studied statistics so that I could help other kids in my community.” Hernandez’s widely varied activism includes speaking with at-risk youth at what she calls alternative schools. “It’s important that young people have someone to look up to. A lot of times just having that conversation can change their life.”

The fallout from that early attack has surfaced even in this race. Hernandez recently emailed that “It’s disappointing that a candidate claiming to support women doesn’t address or stop the misogyny from their supporters attacking how I look, from my facial expressions when I sit to how I speak. As someone who has lived with chronic spinal pain, “sitting up straight” and not having “resting b**** face” [sic] is not an issue of not caring but instead the pain I live with each and every single day as a survivor of an attack that has caused permanent damage.”

For Hernandez, social justice causes like women’s rights, prison reform and immigration issues are close to home. Her mother, Consuelo, born in the border town of Nogales, Mexico, still has close family ties to that region, which is only 68 miles from Tucson. Hernandez speaks movingly of the suffering of people there trying to find refuge in the United States.

Hernandez’s mother is one of 13 siblings, and though her own father did not support her early dream of becoming a doctor (supporting her brother instead), she graduated from the University of Guadalajara with a degree in laboratory clinical pathology and became the first woman in Nogales to own her own clinic. After she married 30 years ago and moved to Tucson, she became a stay-at-home-mom.

Hernandez identifies not only with these Mexican roots, but also with her Jewish forebears. Her mother’s father, and both his parents, “were Jews, Mexican Jews, and they came from the Cohen family; they went from being Cohens to Quinones. My grandmother [Consuelo’s mother] is Catholic, so my mother’s father is the one who—whether or not he ever practiced or wanted to talk about it—I mean, he’s Jewish because his parents were Jewish.”

Hernandez is a Jew by choice as well as by ancestry. Although her father is Catholic, he supported her official conversion to Judaism. “My parents don’t like quitters. So my dad and mom made sure that if I was going to start something I had to finish.” She was thorough: studying with Rabbi Stephanie Aaron, at Tucson’s Congregation Chaverim, immersing in the mikveh, and adopting the names of her great-grandmothers Malka and Librada— meaning, Hernandez jokes, that she could be called “Queen of Freedom.”

The process of conversion felt like coming home. “I never felt like I really converted into anything. Does that make sense? I always felt like it was who I was and a part of me.” Rabbi Aaron had been a mentor during Hernandez’ difficult teenage years. “We really just clicked,” she says of the rabbi. “Rabbi Aaron helped me cope in my own way. I really needed the spiritual and religious path that I was seeking. I was kind of lost and trying to figure out my life.”

According to Rabbi Aaron, Hernandez is “genuinely devoted to the service of tikkun olam (repairing the world), intuitively understanding that to repair the world means to repair your own soul. When she learned that she is a Jew, she had to know.…[She has] incredible Sephardic Jewish roots, mainly on her mother’s side, but on her father’s side too, born out of the Mexican Inquisition, that are indestructible.” In addition, “Hernandez’s parents redefine the notion of what support for your child means.”

The culmination of the conversion process was her naming ceremony. “My family is big on milestones,” she says. So what started out as a private conversion celebration turned into “a big Mexican pechanga.” According to Rabbi Aaron, the synagogue was packed with community in support of Hernandez’s “choosing Jewish life for herself.”

Hernandez’s later bat mitzvah was celebrated with another big party, the first held at the Jewish History Museum, where Hernandez and her father volunteer as docents. “My mom was very emotional, because it reminded her of her [Jewish] roots and her family.” Hernandez hopes to take her parents to Israel; she and her two siblings (who identify as Jews without having had formal conversions) have visited separately.

The Jewish community has always been Hernandez’s base, through both volunteer work and employment during her teen years and beyond, including stints at the Jewish Federation of Southern Arizona. Most of the financial support for her campaign comes, she said, from Jews—including from Jews all over the country whom Hernandez met volunteering at aipac, and as president of the pro-Israel club at the University of Arizona. When she receives campaign contributions in amounts like $18 and $36, Hernandez said, “You can tell they are from our community.”

The family may be a political dynasty in the making. Hernandez’s brother Daniel, 28, is a legislator who has just completed two years in the Arizona House of Representatives and is now up for re-election. And her younger sister, Consuelo, is running for the local school board on which their father also serves. The family members all support one another’s campaigns actively, driving around by car and truck to ring doorbells. Daniel Hernandez is something of a local hero; he is the man who, as a college student and legislative intern, saved the life of Representative Gabby Giffords when she was shot at a rally in her district in 2011.

The family is making history again this season. After having been the first Arizonan trio of siblings to be elected delegates for the 2016 Democratic presidential nominating convention, they are also, from what they can tell, the first three siblings to all seek elected office simultaneously in Arizona. “We’ve done everything together ever since, you know, we were teens. As my brother said yesterday, it’s really because we don’t have anyone else.

“It doesn’t matter where we are, whether my sister’s in New York or my brother is in D.C., we all return home for the High Holy Days, just to be together,” she says. “We always make it happen. We add our Mexican touch to everything, including on Passover, when a friend brings a bucket with the questions asked during the Seder—in every language you can think of, so my mom usually reads them in Spanish. My mother speaks English, but she prefers to speak Spanish.”

After living in the U.S. for 30 years and helping other immigrants obtain citizenship, Hernandez’s mother finally became a citizen herself in 2016—“in order to vote for Hillary Clinton,” says her daughter.

“Being a daughter of an immigrant is part of the reason why I started Tucson Jews for Justice,” Alma Hernandez says. The group, launched in March 2018, wants to be a Jewish presence at rallies supporting Dreamers, gun violence prevention and health care, among other causes. Hernandez speaks of immigration as a particularly Jewish concern. “Everything that I do is because I am a daughter of an immigrant who came here from Mexico, and who knows that as Jews we’re all immigrants, and that it’s our duty to do what we can to welcome others that come here.”

Hernandez undertook Jewish studies in college and became so dedicated a volunteer at the local Jewish history museum that she was given a key. “How can you not hear the stories and read the stories [of the Holocaust] and know everything that’s happened to people and not feel something in your heart and feel like you need to do something to help others?” she asks.

In New York’s harbor, the iconic Statue of Liberty is seen as representing a universal welcome to immigrants, with the Emma Lazarus poem at its base inviting less-hospitable places to “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…” The “wretched refuse” arriving in the New York Harbor were mostly at the end of a journey from places where they had been treated harshly. At the southern border of the U.S., though, there seems to be no parallel symbol of welcome, nor even the pretense of welcoming immigrants, and Hernandez has seen that border up close for most of her life.

“People think oh, it’s the drug dealers, oh it’s this – and I’ll tell you right now, the drug dealers aren’t going to be the ones walking the desert with their child to get here. The drug dealers have outsmarted everyone and they do a really good job of crossing the drugs over without having to put themselves in danger.”

In May, vilification for Hernandez’s activism came from a particularly unnerving source. “I was attacked by David Duke for doing what I thought was right, helping families who are trying to seek asylum, crossing the border. They [the prospective immigrants] were waiting on the Nogales border, and my mother’s from Nogales, so for me it was very personal,” she says. “How can we not help provide food, the basic necessities which I would hope that anyone would be willing to give to any person?” she asks, her voice growing thick. “I get emotional because I don’t know how anyone can deny food or water or basic needs to any human. I’ve had family members that are Dreamers and have actually crossed the desert to get here. …I’ve had children pull onto my legs and tell me to please give them back their mom or dad. To not be able to help them, it really impacts you.“

News 4 Tucson reported that Duke, former Ku Klux Klan Grand Marshall, tweeted from an article describing Hernandez as “not the only Jew trying to help families crossing the border.” The kkk leader then added, “But for her the work is personal.” Duke has been a vocal white supremacist for longer than Hernandez has been alive. “He doesn’t believe in the Holocaust,” she said. “He’s a Holocaust denier, so for him to be using me as a target and the form of a joke is scary, but I’m not going to let this stop me. …We Latinos and Jews are here to stay.”

Her ability to connect across divides may be a prime reason why Hernandez will be honored in November by the Sisterhood of Salaam Shalom®, the Muslim and Jewish women’s organization. The advance announcement of the tribute reads, “Thank you for being a change agent and for being a teacher and inspiration…. You used your feet to pray as you went to the border. We would like to acknowledge your spiritual activism.”

At times, she and her siblings have received flak from the left for being involved with right-of-center pro-Israel organizations like aipac and Stand With Us. “People try to make us choose between being progressives and being pro-Israel,” she says. “I’ve always told people no one can ever tell me I can’t be pro-Israel and pro-Palestinian and progressive. I feel as someone who really, truly cares about people, I can be all three.”

Joan Roth is Lilith’s photographer. Susan Weidman Schneider is Lilith’s editor in chief.