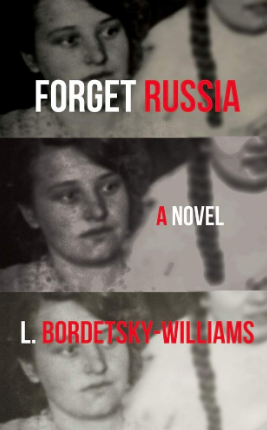

Forget Russia: a Q&A with L. Bordetsky-Williams

“Your problem is you have a Russian soul,” Anna’s mother tells her. In 1980, Anna is a naïve college senior studying abroad in Moscow at the height of the Cold War. She’s also a second-generation Russian Jew raised on a calamitous family history of abandonment, Czarist-era pogroms, and Soviet-style terror.

Novelist L. Bordetsky-Williams talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about how Anna’s experience both illuminates the dark corners of her family’s past and shines a light toward the future she is fashioning for herself.

YZM: You write about Russia with such affection and intimacy; what is your relationship to the country?

LBW: It all started when I began reading Dostoevsky in high school, and I found myself imagining the dark and winding streets of St. Petersburg. Then when I was in college, and I started studying the Russian language, it opened up a relationship with my quiet Russian Jewish grandmother. She was hard to connect with because she didn’t speak much. But I found a treasure trove of tales and grief behind her silence that were central to the formation of my own self-identity. She taught me the songs of unrequited love from her girlhood, that time before she came to America when she was just sixteen, before she lost her own mother in a pogrom. It was a tragic story that no one in the family seemed to know about. Finding out over time, that her mother had been raped and murdered in a shtetl in the Ukraine was shattering. Still, as an old woman with a thick Russian accent and Yiddish as her first language, she represented the magic of another, older world. She actually spent the last years of her life singing the love songs of her girlhood to herself as a way of dealing with the extreme difficulties of going blind. Yet, as I came to understand the tragedy beneath her silences, I came to view Russia as a land of danger and terror as well as a place one loved with an intense ambivalence.

YZM: Do you think the promise made by the revolution—that life would be better for Jews under the new regime—was fulfilled?

LBW: Initially, life did get better for Jews after the 1917 Revolution. They were allowed to move into the cities, which was forbidden under the Tsars, and there was a tremendous hope and optimism that anti-semitism had been eradicated. Under Stalin, the Jews did not ultimately fare well. As I researched this period, I discovered that in 1928, according to the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Biirobidzhan, which was located in the Soviet Union on the Manchurian border, was designated as a Jewish agricultural colony. It was a very remote place, located five thousand miles from Moscow, with exceedingly difficult living conditions. As I read about Birobidzhan in 1931, life there sounded harrowing—no plumbing, and growing anything on the land sounded close to impossible. In Forget Russia, I have a character who has come to Leningrad from Birobidzhan with her husband since she could not withstand the harsh living conditions. She is another Russian Jewish immigrant who left Russia and returned in 1931, excited by the Bolshevik Revolution and disillusioned with life in Depression-era America. By 1934, Birobidzhan was considered a Jewish Autonomous region with the goal that this region would function as a type of Jewish homeland. From 1936-1939, Birobidzhan was decimated by Stalin’s purges. Many Jews were the original Bolsheviks, and Stalin went after them. While Jews felt the yoke of the Tsars lifted after the Revolution and believed the possibilities for them seemed endless, during Stalin’s brutal purges, Jews, as well as other Bolshevik leaders, were targeted and suffered terribly.

I980, when I had the opportunity to study Russian in Moscow, I saw firsthand the widespread discrimination against Jews. They had trouble getting into the Universities; jobs were limited. There was only one operating synagogue in Moscow, and as I describe in the novel, on Rosh Hashanah, a black car tore down the cobblestoned street where the Jews had gathered to celebrate the holiday as a way of intimidating and terrorizing them. I had never before witnessed such outright anti-semitism like that.

YZM: I see the book as a series of journeys.

LBW: I also see the novel as a series of journeys back and forth across the ocean to Russia and the United States. These journeys also symbolize the idea of self-transformation through journey. In 1980, Anna journeys to Moscow and meets the grandchildren of the Bolsheviks there. Most of these Bolshevik ancestors had been murdered or exiled by Stalin. Her own grandparents, Russian Jewish immigrants, returned to Leningrad in 1931 to build the revolution. The Soviet society and living conditions they discovered upon coming back to Leningrad were vastly different from their expectations. These journeys explore the meaning of identity and the meaning of home to each person. What does it mean to leave one’s home, and how does one create home in a new land of strangers? Does one ever stop longing for the original homeland? These are eternal questions and are particularly relevant now when immigrants are facing so much prejudice and restrictions. Immigrants are not “the other.” They are ourselves.

YZM: Zlata’s rape and murder reverberate through the novel; do you think trauma is transmitted from generation to generation and if so, what effect does it have on the characters?

LBW: This was precisely the question I had in mind when I began the novel many years ago. How does a violent act affect the subsequent generations of women? How is this trauma communicated from mother to daughter? In essence, Anna returns to the Soviet Union to confront her family’s past. Somehow by taking this journey, she is symbolically able to leave some of her family’s grief in Russia, and in a sense, attempt to begin anew. It’s as if she is journeying through her grandmother’s life by returning to the Soviet Union, and working through some of that trauma by taking the journey. It is also important to note that Anna’s grandfather also lost a parent, his father, due to a hate crime in Minsk; yet, he was not scarred by this event. The novel seeks to explore why people react differently to trauma. I don’t believe there is an answer to this question, but the question, nonetheless, is important.

YZM: What about the title—is it ironic? Or a real directive? Is it truly possible for Anna to forget Russia?

LBW: No one in the novel can ever forget Russia, no matter how hard they try. The people Anna meets in the Soviet Union transform her. They, like the Russian land, exist in a place outside of time, and for this reason, it is not possible to forget them.