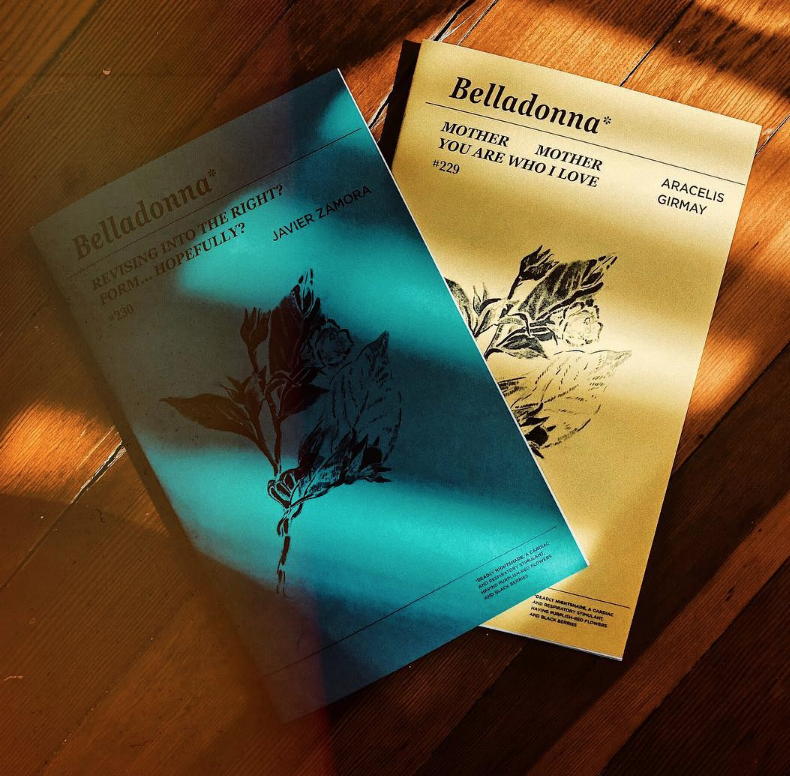

Belladonna Founder Rachel Levitsky on Poetry, Politics, and What Comes Next

Rachel Levitsky calls herself a “lesbian, commie, poet, and polemicist who makes things.” And she does: Levitsky has written three full-length books and nine chapbooks herself, teaches undergraduates, and is the founder of the Belladonna Collaborative, a 20-year-old feminist avant-garde literary salon and publisher of experimental, multi-gendered, and linguistically bold titles.

Among Belladonna’s releases are award-winning texts from writers including LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs (Whiting Award) and Beth Murray, whose posthumous book of poems, Cancer Angel, won the 2016 California Book Award. Levitsky sat down with Eleanor J. Bader in Belladonna’s office.

Eleanor J. Bader: Have you always been a poet?

Rachel Levitsky: When I was a child my dad told me not to be a poet. Writing poetry was not an occupation in the Levitsky consciousness. I did not come out as a poet until 1994.

EJB: Do you know why your father had this attitude?

EJB: Do you know why your father had this attitude?

RL: My parents seemed to value invisibility. My mother had been born in Germany and came to the US as a toddler in December 1939. Her uncle survived Auschwitz, but no one in my family was willing to talk about any of this and I always wanted to know more.

EJB: Is this why you became interested in history?

RL: Maybe. I was a history major as an undergraduate at the State University of New York (SUNY) in Albany and got a Master’s in American Social History. My focus was labor. My thesis looked at the way the cigar industry in Binghamton, NY became segregated by gender.

EJB: But you chose to pursue activism.

RL: I wasn’t interested in pursuing further academic study in History. I plunged into activism in New York City, joining ACT-UP and WHAM!—Women’s Health Action and Mobilization.

My job at the time was with the Home Program of the Bond Street Homeless Center run by Catholic Charities. Every night, five of us would load into a van and drive around Brooklyn trying to convince mentally-ill, chemically-addicted people to come to the Center’s drop-in program.

I did this work in 1991 and 1992, until I got a job teaching adult basic education classes for the Consortium of Worker Education (CWE), an educational organization that serves union members. In 1993-94 I taught English in Mexico. When I came back to the US, I returned to the CWE and eventually got a full-time job running an English as a Second Language program at the Painters and Finishers Apprenticeship program in Long Island City.