The Feminist Who Illustrated “The Wisdom of the Fathers”

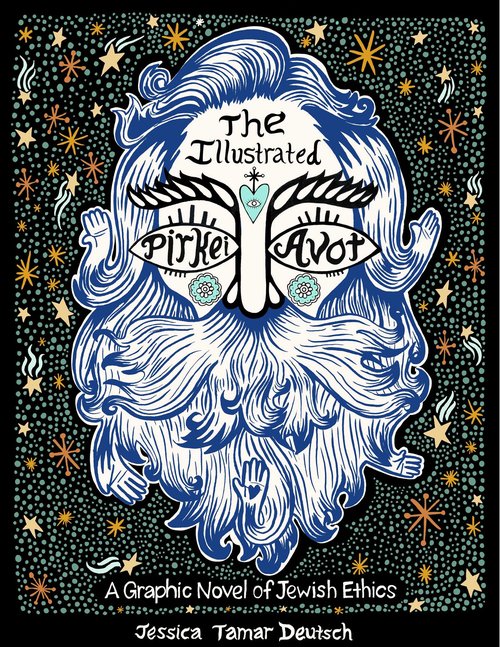

When artist Jessica Tamar Deutsch was finishing her studies at the Parsons School of Design, she decided to illustrate the famous collection of rabbinic wisdom, Pirkei Avot—typically translated as The Ethics of the Fathers—as her senior thesis. It was 2013. Her colorful 128-page effort was then shopped around to every publisher of Jewish texts that Deutsch could find. Rejections piled up. Some bristled at her depiction of pants-wearing women holding the Torah. Others disliked seeing men with their heads uncovered. And still others did not want to take a chance on something they saw as little more than a religious-themed comic book.

Thankfully, Deutsch reports, a small-but-growing Philadelphia company called Print-O-Craft decided to buck the trend and The Illustrated Pirkei Avot: A Graphic Novel of Jewish Ethics, was released in April 2017. To date, nearly 4,000 copies have been sold.

Deutsch sat down with Eleanor J. Bader on a chilly December morning to discuss the book, art, and the creative process.

Eleanor J. Bader: Since the release of The Illustrated Pirkei Avot more than a year-and-a-half ago, you were named one of Jewish Week’s 36 Under 36 in 2018 and are currently doing a Fellowship with LABA, at the 14th Street Y in Manhattan. Can you tell me more about your current projects?

Jessica Tamar Deutsch: I’m presently illustrating two different books. One is being written by Rabbi Jon Leener and will introduce children (and adults) to Rabbi Nachman of Breslov. It’s sort of a Rebbe Nachman 101. The protagonist is a five-year-old girl named Esther.

The other book is being written by Rabbi Simcha Weinstein and is the story of his Jewish journey.

I also design Ketubot, Jewish marriage documents. This includes interfaith couples and incorporates new traditions where women make a Ketubah for their spouse instead of being the one to receive the document. I love when people make up their own customs. I work with each couple to find meaningful texts but I don’t do the actual calligraphy. I have friends who are amazing scribes so when I make art that I want hand-lettered, I gladly collaborate with them.

Lastly, I’m the resident artist at the Lab Shul. It’s been exciting and an education for me to work with communities that practice Judaism differently from one another.

EJB: You’re juggling a lot! What’s your project for the LABA fellowship?

JTD: The idea is to explore the Hebrew word for truth, emeth.

I recently completed a three-day training to become a doula, to help in the delivery room and be a calm support to the person having a baby. Fellowship funding allowed me to pay for the training and I intend to get more instruction before I begin this work. At the same time, I’m learning about death rituals in Judaism and am working with the Chevra Kadisha, the Jewish Burial Society, in Park Slope, Brooklyn. The idea is to be in these two book-ended moments simultaneously and see what happens. I hope to make art from these experiences but I am not yet sure what form the project will take.

EJB: Have you always made art?

JTD: I think you can safely say that I’ve been making art practically since I exited the womb! Before I even went to nursery school, I made a collage by cutting my hair and arranging the strands on paper–and I’ve always painted. In elementary school I became obsessed with Renaissance paintings.

My maternal grandparents were in the textile business so growing up I was around fashion, color, and fabrics. When I got to Parsons, I began with the intention of studying fashion design, swapped over to fine art for a semester, and finally completed my BFA in illustration. Along the way I took several sewing classes but, for me, sewing was soul-wrecking. I’ve always loved drawing best.

EJB: By combining your love to Judaism with your love of painting and drawing, you’ve figured it out.

JTD: I think so! I grew up modern Orthodox in New Rochelle, New York, and was one of those kids who absolutely loved Judaism. In fourth grade I had a cheder-style teacher who taught Torah as a song. Judaism became music to me.

EJB: Have you always been a fan of graphic novels?

JTD: As a kid I read Archie, and I’m only now learning about some of the greats.

When I was at Parsons, I’d walk by a store on my way to class called Forbidden Planet. I discovered a book there called Blankets by Craig Thompson. I bought it and remember thinking to myself, ‘This is the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen.’ In it, Thompson described growing up in middle America, in a religious Christian family, falling in love and experiencing heartbreak for the first time, and then moving to New York City. This spoke to me.

The art I like best tends to make the everyday look sacred and Thompson did that. It was eye-opening to find his work.

EJB: How about your relationship to feminism?

JTD: People have asked me why, as a feminist, I made a book about male wisdom. It’s a good question, but I think we have to deal with things we find uncomfortable in our traditions.

I think that some of the discomfort comes from the progress of Jewish feminists, something I benefit from. People my age can’t relate to a time when only male voices were canonized.

Rabbi Eve Posen and Lois Sussman Shenker have written Pirkei Imahot: The Wisdom of Mothers, The Voices of Women as a feminist response to the Pirkei Avot. It’s fabulous. They’ve written it in the way you would construct a Mishnah, by turning to powerhouse women for advice. The people who are making new Mishnahs today are keeping Judaism alive.

EJB: How did working with the Hebrew text affect you?

JTD: What I love most about Hebrew is that it is a playful language and the ways my publisher and I interacted with my manuscript allowed us to title it The Illustrated Pirkei Avot. Perkei means chapters of collections and avot can be translated as fathers, but it can also be translated to mean important things; the book can be called a collection of the most important teachings or the most important wisdom, instead of Ethics of the Fathers.

EJB: How has your feminism come up against the realities of different Jewish communities?

JTD: I often assume that what I am up to is considered unconventional, but I may be wrong about this. I was speaking at the Sixth Street Synagogue in Manhattan’s East Village about the book and there was a man there, dressed in black and white, with peyes. After I spoke, he came up to me and said it was inspiring to him to hear a woman deal with Mishnah in a serious way. That’s change happening.

Still, there are things in Judaism I don’t want for future generations. For many women, diving into Jewish texts can seem daunting, I am disheartened when women assume they must rely on male teachers. We forget that the Torah is something manageable, something they can learn. When women role models aren’t present as clergy, it’s difficult for women to see themselves in a direct relationship with Torah. They may miss an opportunity to develop their own study skills or learn from someone who might have a better understanding of their lived experience. When I want to learn something, I go to a text, and on my own, try to find an English translation and then wade in.At the same time, while I’m grateful to have supportive male colleagues and teachers, I often have to deal with being the only female voice in a particular space. it can wear me down and feel lonely.

EJB: So, how do you handle it?

JTD: I’ve started writing something I call The Torah of my Kishkes: The Diary of a Twenty-Something-Year-Old Jewess. It’s the place I put my thoughts on Jewish practice, the disappointments, joys, and hopes for the future. It’s been the best way I’ve found to deal with the knots in my heart. I also make sure to take care of myself by running, doing lots of yoga, seeing friends, and playing music. In addition, I’m now taking a dance class for the first time.

EJB: What is your favorite art-making activity, something that you do for pleasure?

JTD: I love being outdoors with my sketchbooks. Sketchbooks are the best. There is no expectation or judgment when you use one.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.