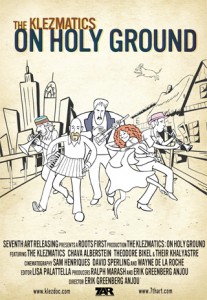

Feminists in Focus: Reporting back from the New York Jewish Film Festival 'The Klezmatics: On Holy Ground'

At the 20th New York Jewish Film Festival, presented by The Jewish Museum and the Film Society of Lincoln Center (through Jan. 27).

At the 20th New York Jewish Film Festival, presented by The Jewish Museum and the Film Society of Lincoln Center (through Jan. 27).

For any woman musician who’s fantasized about being the only babe in the band, “The Klezmatics: On Holy Ground” is a cautionary tale not to be taken lightly.

The Klezmatics describe themselves as a dysfunctional family. In a music industry falling apart, they went from winning a Grammy to firing the agent who helped make it happen, to seeing their record label go out of business, the office replaced by a methadone center. They’ve gone from being one of the first neo-klezmer bands back in the ‘80s to bringing the music back to Germany and Poland and they’ve performed before capacity audiences at Town Hall in New York City and Walt Disney Concert Hall in L.A. They’re in their glory on a big stage with an expanded band, Oriental carpets covering the floor and a starry night backdrop behind them.

Members come and go, including original fiddler Alicia Svigals, but some of the original founders are still with the band after 24 years. All this is chronicled by filmmaker Erik Greenberg Anjou (“A Cantor’s Tale” 2005), who followed the band’s highs and lows for more than three years.

The film could have used a firmer hand – imposing more cinematic order on of the chaos of the Klezmatics’ life by group decision. But once the six-member band starts trusting the filmmaker behind the scenes, the story gets interesting. (Though those hoping for a film that’s non-stop music will be disappointed.)

Fiddler vocalist Lisa Gutkin speaks for plenty of women on the move when she says she’s given up any sort of steady relationship for the band. “I have nieces,” she says. The guys at least have chalked up one failed marriage, a gay alternative family where the male partner has fathered three children for a lesbian couple, and the more-or-less traditional family with working wife and kids – one autistic.

Gutkin takes on the thankless role of raising the issue of their being successful but unable to make a decent living by band alone. She also raises the issue of commitment: What’s horn player Frank London doing — agreeing to save a pecific date for a possible performance when he’s ready to dump them if a teaching gig comes along. He promises to be more honest next time. (No comment.)

At the question session after the screening, Gutkin said, “I think I do wish I weren’t the only woman in the band but part of me enjoys the role.” Speaking afterwards, when I told her she came across as the one adult on the bus, Gutkin said, “I’ve had a lot of therapy.”

Pre-psychiatrists, pre-Social Security, klezmer bands went from town to town, playing at weddings and bar mitzvahs, bringing news from one shtetl to another. Roving bands with insecure existences, playing joyously soulful music.

The film harks back to these roots with archival footage of a klezmer band playing as a white-gowned bride is led to the chuppah. Hey – we hope this happens for Gutkin – nieces just aren’t enough. And under the chuppah, we’d like to see her circling her beloved, wildly playing her violin.

-Amy Stone