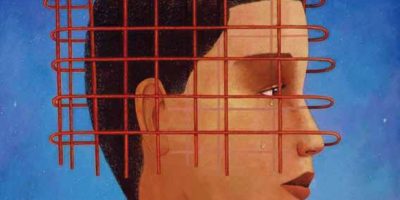

Robert Walker Macbeth, “Our First Tiff,” 1878.

When Food and Love Collide

Aaron and I lingered at the buffet table, enormous bowls of pasta salad and vegetables spread out in front of us. The event celebrated the purchase of a pre-World War II Torah that had been recently rescued from its hiding spot in the basement of an old synagogue in Romania.

“It’s funny, that guy over there just asked if we were dating,” I mentioned, as I reached for some tortellini with pesto. “It’s not the first time I’ve heard that question. Earlier this week, someone asked me the same thing.”

“Well, it’s not like I haven’t thought about it,” he replied idly as he scooped carrot salad onto a paper plate.

I stopped mid-spoonful, frozen. I hadn’t expected that response. “I — I don’t think now is the best time to talk about this,” I said.

He shrugged and said, “Why not?” without looking up from the food.

“Well, I’ve been thinking about it, too,” I said carefully, which froze him as well. Carrot salad ignored, he looked over at me.

“Maybe you’re right,” he said slowly, “maybe this isn’t the best time to talk about it.”

That moment at the buffet table marked a change in our relationship. But it was only the latest food marker in our time together. Food had originally been part of what kept us apart.

We’re both Jewish. We often go to the same service to pray, a minyan that pushes the boundaries of the Orthodox movement by allowing women to lead parts of the service. But unlike me, Aaron keeps Shabbat. And he keeps kosher. Strictly.

To my mind, I do keep kosher. I grew up with separate meat and milk dishes. I don’t eat pork or shellfish and, if I were to eat meat, would only eat kosher meat. My dishes are all vegetarian and have never been used for any meat meal. But this wasn’t enough for him. I don’t look for a hekhsher on everything I buy, so he wouldn’t eat food cooked in my kitchen. If he eats hot, cooked food out of his house, he only eats it in strictly kosher homes and restaurants.

We’d known each other for years. For the past six months, we’d been spending a great deal of time together, going out regularly to a neighborhood bar to catch some bluegrass, grabbing a beer and discussing our love lives. When we’d talked about dating (other people, of course, not each other), I said I couldn’t date someone who wouldn’t eat out at a restaurant with me. He said he’d never date someone who ate at non-kosher restaurants, as she’d expect the same of him.

And yet I knew I was playing with fire as I increasingly invited him to join me at events around town. I loved talking with him. I wanted to hear his opinions. I wanted to see his huge smile and enjoy his quick wit, his ability to find a come-back to any taunt, or a random piece of information to complement any topic. Suddenly I realized I had a problem: I was falling in love.

A week after the encounter at the buffet table, we went out on our first official date. He took me to sushi: he could eat the fish (uncooked), but wouldn’t eat the rice (cooked). The sake slid down our throats, spicy and sweet. We moved on to coffee (hot drink — not a problem, as it’s prepared in its own container), and he took my hand, stroking my palm. Chills flew up my spine. When he kissed my fingers I knew it was time to leave the restaurant.

Despite the food barrier, we tumbled into the relationship with a speed and intensity that belied our religious differences. I suddenly, shockingly, had a boyfriend who could not take me out to dinner, except, generally, at one of a couple of local kosher restaurants. So instead, we cooked — at his house. We’d stop off at the supermarket and pick up whatever looked good, frying up tofu and vegetables, ad-libbing sauce for pasta, covering our hands in sticky fruit juice for mango and black beans. We grabbed left-over vegetables in the morning and threw them in a pan with eggs and spices. He said he’d rarely eaten so well.

Before we started dating, Aaron insisted it didn’t matter that he could basically only eat raw vegetables at non-kosher restaurants. “I can’t tell the difference between good and bad cooking, so I don’t mind.”

I quickly learned that was a lie, or at least a necessary delusion. I’d hold out the spoon while cooking and he’d sip it, wait a moment, then pronounce what should be added — lemon juice, salt, hot pepper, cumin. I trusted his taste. I called him a closeted foodie.

One Friday night we invited a half-dozen friends over for Shabbat dinner. We spent the afternoon in the kitchen. He played sous-chef as I called out the steps for the recipes. The sauce for the fish bubbled on the stove as he smashed pistachios to go in the quinoa and I diced an array of jewel-toned vegetables for an Israeli salad. We carried the vibrant platters out to our guests in celebration of the gusto with which we’d performed this dance of domesticity. I surveyed the table with pride, relishing our shared culinary adventures, our love of food and community.

But I missed sharing other food experiences with him. I thought about visiting a close friend later that summer, and how she wouldn’t be able to cook him her Armenian crusty rice or whip up a vegetable stew. I regretted that I couldn’t introduce him to the salty sweet vegetarian kibbeh at my favorite Middle Eastern hole-in-the-wall, or the earthy, locally foraged mushrooms at a neighborhood French bistro.

Then, I started to think about traveling. And food.

I leave the country at least once a year. I’ve sipped soup with a Thai monk, dived into a hot fish taco with Mexican fishermen, gorged on rice and avocado salad after a day of hiking in Peru. How could we travel together?

And then I began to worry about children — and food. What if we got married and had kids? What if he didn’t want his kids, our kids, to eat at my friends’ houses? As the months passed, we talked about our differences in religion, and the conversations forced a number of tough questions to the surface, questions about our different views on the role of women in the synagogue, about Shabbat observance. I told him that I could see changing my life in some ways, living a life more tightly bound by Jewish strictures. I was willing to consider, for example, having a kitchen that would meet his kashrut standards. But I would also need to know that he could find a way to be more flexible, a way to allow space for my values, too, in any future family we might create together. He listened, but he didn’t say anything, unwilling or unsure of how to answer.

At times I called my friends in a panic. “I love him,” I’d say, “but how will I know when it’s time to break up?”

Finally, over a beer one summer night, he decided it was time. He said that he looked into the future, and he saw struggles ahead, and he didn’t think he was ready to take them on.

Dating Aaron made me examine the ways in which I’m willing to compromise. I already limit my diet by choice, and it’s not always easy. I can practically taste the rich aroma of my friend’s favorite lamb dish at a local upscale Mediterranean restaurant. After a week in Madrid, the rosy glow of cured ham tempts like a beacon from its premium spot on the wall of my favorite neighborhood tapas joint.

And yet within my chosen restrictions, the small window of flexibility allows me an opening to the world. I can eat anywhere, even if my options are limited. My friends can share their love for me by sharing their food. I celebrate the play of an endless variety of flavors and textures that melt onto my tongue and fill not only my body, but my soul. I know this experience will be a part of what I will share with a life partner. Together we will teach our children that they can wander the world freely, experiencing the tastes of cultures and the joy of new friends from any background.

The relationship’s end left me sad. I felt frustrated that two committed Jews who love each other couldn’t bridge the Jewish distance between us. Yet I understood that to Aaron, the rules of Judaism form the basis of his life. And being with him helped me realize that my decision to approach food with greater flexibility is not simply based on laziness, or an addiction to restaurants. It’s part of my life philosophy, as much a part of it as Judaism. I savor the freedom of being able to sit down with anyone, anywhere, and break bread.

Cynthia Graber is a freelance writer and radio producer living in Somerville, MA. You can reach her at www.cynthiagraber.com.