The Paradoxes of Power: Female Edition

IN THE TRUMPIAN DYSTOPIA we now inhabit, which greenlights openly expressed misogyny and aggressively seeks to turn back the clock on abortion rights, it especially behooves us to note that this November marks the centenary of women’s getting the vote in New York State.

IN THE TRUMPIAN DYSTOPIA we now inhabit, which greenlights openly expressed misogyny and aggressively seeks to turn back the clock on abortion rights, it especially behooves us to note that this November marks the centenary of women’s getting the vote in New York State.

Yes, the vote. The mother of all women’s rights.

The common assumption is that no American woman could vote in any election until 1920, when the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution went into effect. But, in fact, women won enfranchisement gradually. Fifteen individual states had at least partially enfranchised women by the time the amendment was ratified. The first was Wyoming, back in 1867, when it was still a territory. New York was the fourteenth, the first state on the East Coast, the most populous to that point, and the success of the suffragists there carried enormous significance. New York, remember, was the state where it all began—in 1848, at the Seneca Falls convention— with the declaration. When women there got the vote in 1917, everybody knew that women all over the nation would have it too, and soon.

So how did they do it? The New York women were the most politically sophisticated, well organized, and socially connected in the nation, reports Susan Goodier in her book No Votes For Women, a study of the anti-suffrage movement in New York. They understood the dynamics of publicity, and got their stories into the newspapers. They staged huge parades and gave 24-hour speeches from cars parked in crowded areas: the theater district, the shopping district known as Ladies’ Mile and outside factories; every 15 minutes a new speaker relieved the previous one, picking up exactly where the other had left off. They rented out vacant stores and placed machines in the display windows that flipped signs over. People would stand in front of the windows, waiting for the signs to change. For years, suffragists regularly descended upon the Albany legislature, packed the chambers, and argued their cause. (Franchise could be extended only by an amendment to the state constitution, which required a referendum—in which, please remember, only New York’s men could vote. That’s right, only the men. Whew.) And to counter the opposition’s oft-repeated claim that most women didn’t want the vote, in 1917 workers travelled all over the state, hitting every city, town, and village, every tenement house and farm, collecting, in all, more than one million individual women’s signatures on a petition. Afterwards they pasted all the pages on boards carried by 2500 women in yet another parade down Broadway, which took place the week before Election Day in 1917.

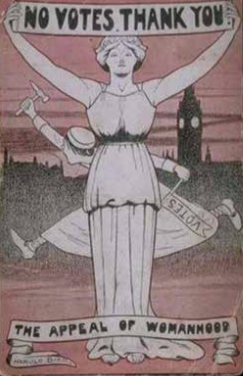

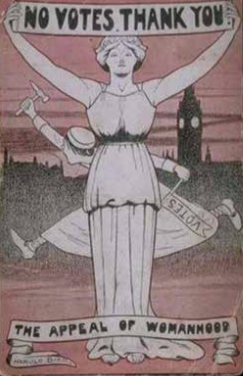

Suffragists were hooted and cursed at—not just by men, but by women, too. New York had a well-organized “Anti”—led by, and consisting of, women. (Men were not part of it, nor were they welcome; indeed, the perception of the Antis was that men would only get in the way.) Wealthy and conservative thinking, the Antis argued that giving women the vote threatened the very foundations of American society—the family. (How sickeningly familiar those arguments are to the ones once used against interracial marriage and, more recently, against gay marriage.) Women’s imperative, the Antis preached, was to teach their children—especially sons—correct morals, and the only place to do this was in the home, i.e., women’s domain. The public sphere—think political clubhouses, saloons, and spittoons—was the male domain, and it was rife with corruption. For women to swim in that cesspool with men would only corrupt them, and, by extension, their children.

SO NOW WE COME to the Jewish angle of this story: One of New York’s best-known suffragists was Maud Nathan, a Sephardic aristocrat and descendant of the 23 Jews who arrived in what was then New Amsterdam, only 34 years after the Mayflower docked in Plymouth. In 1654 these Sephardim founded Shearith Israel, America’s first synagogue. Maud Nathan’s forebears fought in the American Revolution, and her maternal great-grandfather, Rabbi Gershom Seixas, attended the inauguration of George Washington. Nathan, a ninth-generation American, belonged to the D.A.R. She’d never heard of the phrase “The Jewish Problem” until thousands of Yiddish-speaking refugees from Russia and Poland began flooding New York in the 1880s. Her many cousins included Emma Lazarus and Benjamin Cardozo. At age 16, she married her first cousin, Frederick Nathan. (They shared the same last name.) “One of the society events of yesterday,” the New York Times solemnly reported on April 8, 1880, “was the marriage at Shearith Israel, according to the strict Hebrew ritual, of Mr. Frederick Nathan and Maude Nathan…. Wind instruments sounded the first notes of a sensuous Oriental composition…. Nine white tapers, upheld by gigantic candlesticks of bronze, flooded the space below the huppah with a dazzling illumination.” The wedding reception was held at the decidedly not kosher Delmonico’s, the restaurant whose name epitomized Gilded Age New York. These grand Sephardim, while proudly Jewish, were relaxed about following the minutiae of halakha.

Maud Nathan lived the privileged life of a young society matron. (“My mornings,” she wrote in her 1933 autobiography, “were spent in embroidering and attending to my household duties, my afternoons with shopping and social duties.”) But after her and Frederick’s only child, Annette, died in 1893 at age 8, Josephine Shaw Lowell, a dear friend and one of a growing number of New York’s wealthy women who were working to help the city’s exploding population of the poor—the vast majority of whom were immigrants—approached Nathan and convinced her to join her in social activism as an antidote to her terrible grief. Nathan listened—“I threw aside my crepe veil”—and, along with Lowell, formed the New York Consumer’s League, with the aim of educating the public about how stores and factories treated the people—most of them women—who worked for them. Nathan served as president of the League for 20 years, beginning in 1897. During this time Nathan worked with Frances Perkins, who later as Secretary of Labor under F.D.R. was the first woman to serve in a presidential cabinet and was one of the architects of the New Deal. But after a few years of lobbying the Albany legislature to better conditions for the working poor, Nathan realized that nothing was going to change as long as women were disenfranchised. So Maud Nathan joined the suffragist movement, which seemed a natural progression of her political activism.

Or did it?

I ask the question because, from its beginnings, the movement contained an uneasy subtext of anti-Semitism that occasionally burst out into the open. (Which is not surprising: anti-Semitism was then widespread and culturally acceptable.) For example, in 1869, Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s newspaper, The Revolution, wrote that the Jews were not only useless to the country, but were also “a vast accession of voracious, knavish, cunning traders— mere bloodsuckers.”

Nathan, for her part, was proudly and assertively both Jewish and female: in her autobiography she spoke of her “recognized position as a Jewess.” Nathan started Shearith Israel’s sisterhood, and helped found the National Council of Jewish Women in 1896—which, like other Jewish women’s organizations, remained silent on the suffrage issue before the Nineteenth Amendment was passed, according to the Jewish Women’s Archive online exhibition “Feminism in the United States.”

So Maud Nathan was taking a very strong stand as a Jewish woman when she became a suffragist. In fact, she became a major figure in the movement. She was high society, a dynamo at organizing—it was she who came up with the 24-hour speaking gig—and a handsome woman who deliberately dressed elegantly, to counter the oft-repeated accusation that women who craved the vote only did so because they were unattractive and couldn’t get a man. A gifted orator, she was invited to speak to audiences all over—even in churches. She was constantly present in print as well, writing frequent articles and letters in all the leading publications. Her husband enthusiastically supported her politics; in fact, Frederick Nathan even started a Men’s League for Woman Suffrage, and marched in all the suffrage parades that became annual events in New York beginning in 1910.

But Nathan’s suffrage activism did not sit well with her two brothers or her sister. Annie Nathan Meyer, younger than Maud by five years, was an active “Anti.” She was also the founder of Barnard College.

But Nathan’s suffrage activism did not sit well with her two brothers or her sister. Annie Nathan Meyer, younger than Maud by five years, was an active “Anti.” She was also the founder of Barnard College.

Yes, you read that previous sentence right.

Since childhood, Annie—who unlike her sister never attended school—was a voracious reader and writer of stories, poems, and essays. Desperate to get an education, even though her father early on warned her that doing so would ruin her chances of ever finding a husband, she studied on her own and enrolled in what Columbia labeled its “women’s course.” But she soon realized it was a sham: Female students could occasionally meet with professors, but could not attend any lectures, nor was there any place on campus where they could study. Furious, Annie dropped out, continued to write, and in 1887 married her second cousin, Dr. Alfred Meyer, a wealthy German-Jewish pulmonologist 13 years her senior. She then set out to start a bona fide women’s college in New York. Like her sister Maud, she had a soul mate: Alfred Meyer fully supported his young wife’s ideas.

Thanks to Annie’s tenacity—drawing on her family’s deep connections with New York’s moneyed class—Barnard College opened its doors in 1890. Annie was all of 23. The founding mother served on Barnard’s board of trustees, all the while writing essays, novels, and plays, in which she argued her anti-suffrage position with infuriating clarity. To be “Anti” was quite a surprising position for a woman who had the drive and the brains to turn her convictions—that her sex was entitled to the same educational opportunities as men—into the reality of Barnard College. But in Annie’s view, the education that women received at Barnard, or anywhere else, was to be applied only in the home.

She also argued that the suffragists’ claims, that suffrage would do away with all the evils of society—prostitution, graft in politics, war—was ridiculous. Her reactionary ideas were in lock-step with the “Antis” philosophy, and based on a position of extreme privilege, which was something she took for granted. In 1911, as women were pushing hard for a referendum on the vote in New York, Annie spoke at Barnard—it was the end of the spring semester—at a debate sponsored by Barnard’s suffrage club. The subject: “Resolved: Women Need the Vote.” She said: “Nature has no place for the unmarried woman. You girls who would throw yourselves into life’s arena on an equal basis with men— think twice. Is there not just as much as a duty for you in being sheltered? In even spending your father’s and husband’s money? You have the wrong idea of being sheltered. Besides woman’s lack of logic and clearness stands in your way. If women are elected to office a bad woman will win out every time.”

When four months later—the beginning of the fall semester—12 students started a branch of the Women’s Suffrage League at Barnard, Annie was livid at the “intrusion of outsiders into college life.” “I greatly deplore the existence of such an organization among the undergraduates…It seems to me dastardly, in fact almost criminal, for these older women to foist their theories and methods of promulgating them upon these untried impressionable minds…. If the girls are induced to make themselves conspicuous on the streets or do any sort of thing that would make them appear ridiculous or undignified I think we will have no difficulty in limiting the activities of the new league.”

Oh Annie! Whatever were you thinking? Long after women got the vote, she never stopped justifying her reactionary position. In her 1951 autobiography, she declared that she remained an Anti, even though suffrage did not bring about “the dreadful results that the extremists prophesized.” Still, she insisted that giving women the vote “has done no good.” And finally, the parting shot: “There was no question in my mind that at the bottom of the intense desire for the ballot lay—sometimes hidden, sometimes quite openly—a great deal of sex jealousy amounting in many cases to sex hatred.”

SO WHAT ARE WE to make of these two sisters? They had so much in common—both so accomplished, so powerful. They also shared a tragedy: Annie, too, lost her only child, also a daughter, Margaret, when she was 29 and newly married. So why did they have diametrically opposing views over one of the most pressing social issues of their day? Some suggest that Annie turned “Anti” just to spite Maud. Why? We don’t know. Families are complicated; remember that famous quote by Tolstoy. But in Annie’s autobiography, published five years after Maud’s death, Annie describes the resentment she felt towards her older sister when they were children. Her anger is palpable. In her book Annie also dished up other unhappy stories about her famous family. We learn that despite their luxurious beginnings, the Nathan sisters had a tragic childhood. Their father was a habitual philanderer; once, Annie, age three, out in Central Park with her nurse, saw him with another woman on his arm. When she ran up to him, Robert Weeks Nathan pretended not to see his little daughter. After losing the family fortune during the great 1873 financial panic, he moved the family to Green Bay, Wisconsin, then returned to New York, leaving his four children with their mentally ill mother. Annie Augusta was institutionalized in Chicago, and the children returned to New York to live with their father after their mother died. It is not clear how; some suggest she committed suicide.

Were the sisters estranged? Certainly at times: According to the late Stephen Birmingham, in his 1971 book The Grandees, about New York’s old-money Sephardim, Maud Nathan and Annie Nathan Meyer both attended a charity event in their eighties. They arrived separately and did not speak to one another. (Birmingham doesn’t say where this story came from, but he may have heard it from a family member whom he acknowledges in the prologue). Still, when Annie and Frederick Meyer’s 50th anniversary was celebrated at the Columbia Women’s Faculty Club in 1937, Maud was there: According to the New York Times, “Maudie,” as Annie sometimes referred to her sister, “presided over the tea.”

Alice Sparberg Alexiou, the author of Jane Jacobs: Urban Visionary (2006) and The Flatiron: the New York Landmark and the Extraordinary City That Arose With It (2010), is a contributing editor at Lilith. Her new book, a history of the Bowery, will be published in the spring.