Reading George Eliot in Jerusalem

Who knew that the 19th century feminist novelist — decidedly not Jewish — was the woman who helped shape the women who shaped me?

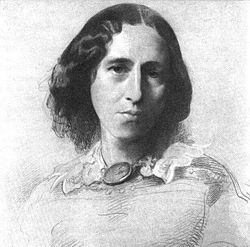

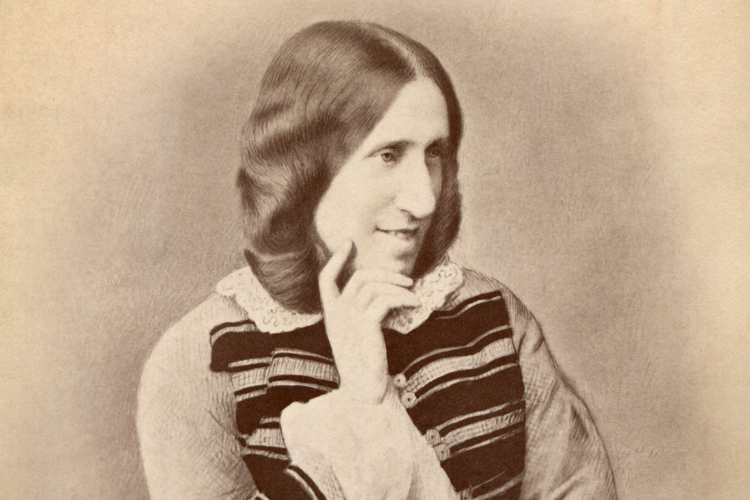

Recently, holed up against the rain and wind of a Jerusalem winter, I asked my husband, who was headed to the library stacks of Hebrew University, to try to find me Volume III of The Letters of George Eliot. Eliot, the author of Middlemarch, Daniel Deronda and The Mill on the Floss, is perhaps the most intellectual of the Victorian-era novelists; she is certainly the one I love best.

He returned triumphant, and time passed quickly as I lost myself to The Letters — the “characters” known, the dramas identified, everyone’s gifts and flaws in high relief. Outside my window, the rain and sleet looked positively London-like, and I had to remind myself that I didn’t have to get to the British Museum any time soon.

Suddenly my two-year-old pitched a bowl of pretzels to the floor and the book fell from my lap, an ancient slip of paper escaping the equally ancient envelope on the inside of the back cover. It was the sign-out card. Pre-bar code, pre-computer printer, this was a typed index card. Title, author, Library of Congress code, and four lone, faint signatures. The wonder of the human signature!

In block-penciled letters, “SHALVI.” February 22, 1958. Another check-out six years later, also Shalvi, November 1964. Then another gap of six years, November 1970 — the month following my birth — and now, more of a penned scrawl, “A. Gottlieb.” Ah, George Eliot, I thought, you genius, you organizing principle of friends, societies, communities of thought and feeling. And a last signature, “Margalioth,” no date.

I was dumbstruck. It was thoroughly conceivable that no one had used this volume in the last half-century except myself, Alice Shalvi, Avivah Gottlieb, and one unidentified friend. Shalvi and Gottlieb (now Zornberg) are Jewish heroines for our times. I held the index card aloft; it was an announcement of sisterhood.

I first encountered Avivah Zornberg when I was 18, studying at an Orthodox girls’ seminary in Jerusalem. Nothing was going right. I couldn’t stomach the lectures about women’s “modesty” nor concede that marriage and childbearing were just around the corner. I envied my male friends at the great houses of study (male only), learning side-by-side with those who’d devoted their entire lives to Torah. It was a wilderness of disappointment until I encountered Zornberg, a scholar who was making new meaning out of Torah, poetry, philosophy, and history, and who invited me, for two hours a week, to come with her.

Two years later, as a student at Barnard College, I discovered a feminism that seemed irreconcilable with my life as an Orthodox Jew. And just as unexpectedly as Avivah Zornberg had appeared in my life, so, too, did Alice Shalvi. I had gone alone to an Upper West Side brownstone to hear Shalvi speak, and she outlined a feminist activism that was compatible with my Orthodox practice. Seeking support for her newest project, the Israel Women’s Network, Shalvi described an advocacy group that was relentlessly addressing the problems of women’s status in Israel, from their positions in the military to their pensions to their acute under-representation in the Knesset. Taking a pen from my backpack, I signed on to get IWN mailings.

As I sat in my Jerusalem apartment with this unexpected new circle of intimates, I began to wonder. What was it about The Letters that had selected the three of us as readers? What were our common sympathies — of literature, of sensibility, of gender — that united us, in spite of the different worlds into which we’d been born?

Alice Shalvi, the first reader on my index card, recipient of the prestigious Israel Prize, was born in Germany in 1926 and escaped to England with her family in the early 1930s. She studied English literature at Cambridge and social work at the London School of Economics, laying the groundwork for a lifetime of sensitivity not only to text, but to the inequities of the world.

After immigrating to Israel in her early twenties and earning a doctorate in English Literature at Hebrew University, she was a professor there for over 40 years; she also founded the English department at the then-outpost of Ben-Gurion University. She married and had six children.

As principal of Jerusalem’s Pelech School, Shalvi pioneered teaching the Talmud and other advanced sacred texts to religious girls, an innovation that spread to other girls’ schools and set the stage for women to intervene in the previously all-male rabbinic discourses that are central to the workings of Jewish law in modern Israel. When she later took the position of Rector of the Conservative movement’s Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, it signaled to feminists in the modern Orthodox world that we could expect little change from within Orthodoxy. Shalvi works as well for greater social and political equity for Arabs and Jews.

Once, years ago, I was a guest at Shalvi’s home for Shabbat dinner. The very-Catholic novelist Mary Gordon was there (she’d been my mentor at Barnard) and we talked about the Pope, Catholic politics, and Shakespeare. We did not talk about the political or intellectual future of Jewish girls and women, or of the likelihood of reconciliation between feminism and traditional Jewish practice. Still, as we left the Shalvis’ home, Gordon said to me, “You see? You really are not alone.”

With The Letters in my hand, I wondered about the connection between Shalvi and Eliot. As a girl, Eliot had been ardently evangelical, but she grew up to articulate a form of faithful humanism instead of Christian deism. She engaged with all the philosophical, theological, scientific, and historical issues of her age, and she emerged with the exquisite, long-lived, mid-Victorian novel.

More especially, perhaps, Eliot wrote novels about girls and women born into a moment that was not yet ready for them, who yearned to “shape their thought and deed in noble agreement,” as Eliot put it in Middlemarch. Women’s “human hearts” may have been “beating to a national idea,” Eliot wrote, but no public or epic life was available to them. If it were available, Eliot said, it would doubtless preclude a life of marriage, love and family.

It made perfect sense, I thought, for Alice Shalvi to read her letters more than once.

From the hands of Shalvi, The Letters of George Eliot passed six years later to Avivah Gottlieb. Raised in Scotland in a venerable rabbinic family, Gottlieb, too, studied English Literature at Cambridge — she actually specialized in Eliot. Rather than pairing literature with social work, though, as Shalvi had done, Gottlieb coupled literature with a deep engagement in classical Jewish sources; she had first discovered these sources with her father and had then pursued them further at Gateshead Seminary.

Zornberg, like Shalvi, made aliyah to Israel, where she married and had three children. Like Shalvi, she lectured in English Literature at Hebrew University, but then she changed direction and began teaching Torah, first in private homes in Jerusalem and later at many Jewish institutions, most devoted to women’s study. I met Zornberg two years earlier than I met Shalvi, and, like many women who cross her path, I’ve considered her a formative teacher ever since. While Shalvi engaged my political and social awareness and struggles, Zornberg spoke to the part of me that embraced the existential, the spiritual, and the poetic.

As long and varied as Shalvi’s biography is, Zornberg’s is powerfully focused. In both her books and her teaching, Zornberg creates an entirely new genre for the study of Bible and midrash, a form responsive to what she calls the “murmuring deep” — the hum, that is, of what the text leaves unsaid. Zornberg’s approach would not have been immediately intelligible to Eliot, coming, as she did, before Freud and Lacan. But I think Eliot would have been intuitively drawn to her — perhaps as a character, certainly as a peer. Both writers merge their intellect with an uncanny ability to convey compassion for the human experience

In her books, The Beginning of Desire: Reflections on Genesis; The Murmuring Deep: Reflections on the Biblical Unconscious; and The Particulars of Rapture: Reflections on Exodus (two have won the National Jewish Book Award), Zornberg gives voice to the tragedy and pathos of human life from the Bible to our own day, to the difficulty of finding a path in a world where God’s presence feels muted and our steps are shadowed by doubt. Here, I think, George Eliot nods her head in agreement.

Unlike many popular lecturers, Zornberg teaches above the heads of many of her listeners, taking inspiration from a startling array of thinkers. George Eliot did likewise. As Anthony Trollope put it, she “fired above the heads of her audience.”

While Zornberg rarely speaks of feminism outright, her writings, like Eliot’s, clearly derive from being born into a world with no obvious place for a woman like herself. Both women hear the “roar on the other side of silence” that Eliot associated with moving out of moral stupidity into a sense of the primacy of others’ lives and needs. Neither Eliot nor Zornberg were actively political, but in their books and their lives they are deeply and intrinsically so.

Here in Jerusalem, there is a street named after George Eliot, most likely because of her proto-Zionist novel, Daniel Deronda; required reading for many Israelis in the 1950s. But that name was actually a pen name. The writer signed the majority of her letters at mid-life “Marian Lewes.” Most readers assume Eliot took this pen name because women’s books wouldn’t sell as well as men’s, but that’s historically false. By the third quarter of the 19th century, approximately 75 percent of English novels were written by females, with males only regaining the field near the century’s end.

Marian Lewes took on her pen name because she was a radical. She braved the storm of familial and social censure to live with a man who remained in an open marriage to a woman who herself had a lover. Shalvi’s and Zornberg’s lives could not be further from this; they chose marriage and motherhood. But never mistake traditional lives for non-radical propositions; both have forged extraordinarily bold paths for Jewish women.

When I pick the library card up from the floor on that snowy Jerusalem afternoon and then rescue it from my small daughter’s tight grasp, I wonder if it would be wrong to keep it. Hebrew University will, after all, eventually standardize its bar codes, as books slow to be checked out make their appearance at the circulation desk. Someone will likely throw the card away.

Neither my name nor my husband’s is on the faded card, which seems right to me. And I don’t know who “Margolioth” was or is, in spite of Google. I know only that the name means “pearls” in Hebrew, something Eliot, who studied Hebrew, would have known, too. Untold histories merge with told ones, as do multiple countries, religions, languages and eras. Marian Lewes never had biological children of her own, but among us she has many daughters. I find it fascinating that some of her most notable children are Jewish women raised to be both Orthodox and modern.

When I close The Letters of George Eliot, setting the index card to hold my place, I remember that as a girl, I, too, loved to write and receive letters. What I loved was the stirring back-and-forth, the question-and-answer, of people not in the same place, but also entirely in the same place.

I will keep the index card.

Ilana Blumberg is associate professor of humanities at Michigan State University and the author of Houses of Study: A Jewish Woman among Books, winner of the Sami Rohr Choice Prize. She is currently on sabbatical in Jerusalem.