from “Sacred Fuse Box Closet”

Architects have always known that place can affect our feelings of holiness. Now we have clues about how women’s experiences can create a holy space in the cellar of a shul, under a tree, behind a file cabinet, even (despite the objections of men) at the Western Wall. [Summer 1996]

Art: Gil Oberfield

When my father died, I decided I was going to continue saying Kaddish once a day for the traditional eleven months and one day. By chance, a “Minha map” appeared in the mail at work from an Orthodox organization, showing offices all over Manhattan where one could find a lunch-time minyan. I’m a Conservative Jew, not Orthodox, but this minyan was my most practical option.

The first time I went, all these businessmen got off the elevator within a minute or two of each other, davened a speedy 15-minute Minha, and then bang, were back at the elevators (it’s the middle of the work day for everyone). No one said Kaddish, so I went out to the elevators after the men, and I said, “Isn’t anybody saying Kaddish here?” and they said, “No.” So I said, “Well, I’m saying Kaddish,” and one of them goes, “That’s interesting,” and I almost cried. Another one says, “You need to tell one of us that you’re saying Kaddish, and then we’ll say it, and you can say it along.”

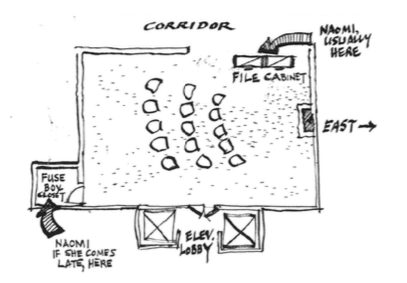

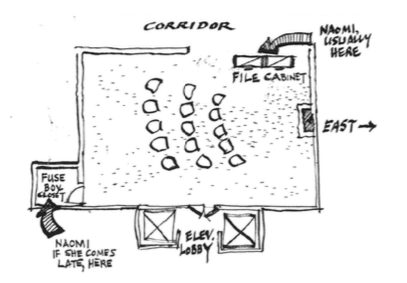

So I went to this minyan five days a week for the year. I dressed modestly so I wouldn’t offend them. I think I wore skirts the whole time—which now seems unbelievable to me since I generally wear pants to work. One day I get to the minyan a little late, and a man says to me that if I come late I should stay in the fuse-box closet, and not walk past the men and distract them to get behind the filing cabinet. It sounds ridiculous, but that’s what he said.

A few times that year I ended up praying in the fuse-box closet (I was always the only woman at the minyan), which didn’t feel a whole lot different from behind the filing cabinet —though I probably felt more angry in the fuse-box closet.

Actually, the whole experience made me angry, but I must have liked feeling that way —maybe because I was mad that my father had died, and it was easier to feel enraged at the injustice of these men than to feel devastated about my father. I wasn’t going to let these men take away from me the comfort of saying Kaddish—this comfort belonged to me as well as to every Jew. I felt that my fury was on behalf of other women—it was an injustice to all of us.

I’m not so rebellious against God (if it was God that made my father die). I don’t know that I could quarrel with God about that, but I could feel righteous indignation about the small mindedness of these insensitive men.

Somewhere near the end of my Kaddish year, an Israeli couple, in the accountant’s office for business, were prevailed upon to stay for the minyan, and the woman joined me behind the filing cabinet. It was the only time there was ever another woman there. We talked in Hebrew, and she was very indignant in particular, for some reason, about the chairs—that the men had chairs but I didn’t. I myself hadn’t minded about the chairs; it was only a few minutes, it wasn’t a big deal.

The Israeli woman asked me, “Why do you put up with this?” and I answered, “Maybe I need to keep my anger. If I had a chair,” I said, “I’d be comfortable.”