from “Jewish Women’s Philanthropy”

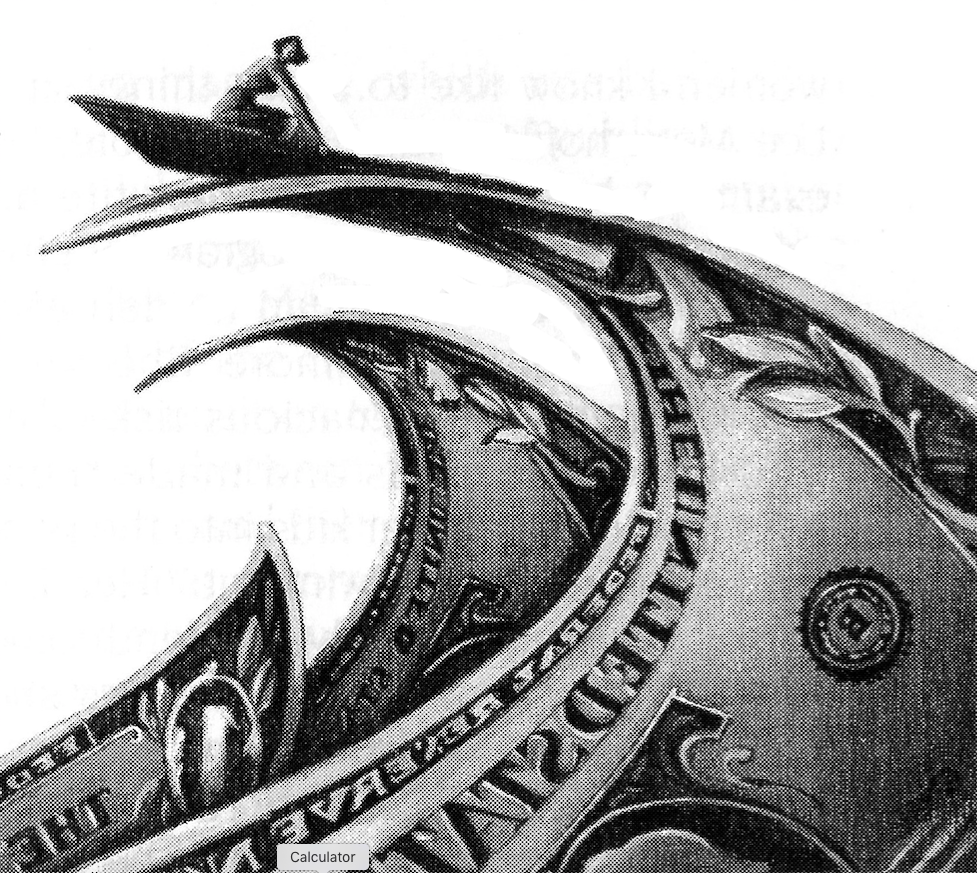

All charitable giving intends to change the world for the better. But the female philanthropists profiled here really want to shake things up, so they’re putting their tzedaka right where their personal politics are. [Fall 1993]

Art: Karen Stolper

Jewish women today control more wealth than ever before —as wage- earners, beneficiaries of estates, directors of companies, board members of foundations and women’s funds, and as the ones in charge of running family foundations while their brothers, fathers or husbands manage the family businesses.

How do the causes Jewish women give to differ from those of other women? The traditional Jewish fundraising method—peer-pressure—has in the past worked well for men, but does it boomerang for Jewish women? How can Jewish women make sure that their philanthropy most effectively leverages change? To find out, Lilith interviewed more than 100 women donors to Jewish causes, as well as professional fundraisers, money managers and psychologists.

In the transition from time to dollars, women’s giving moves in the opposite direction from men’s. First a woman volunteers, or is drawn to the cause; then she writes the check. Women want a connection to the work they support, so it stands to reason that they reach for their checkbooks for causes that really touch them. Here’s a case in point: Rabbi Sue Levi Elwell tells about a group of Reform women rabbis who were approached to fund a faculty slot at Hebrew Union College, the movement’s rabbinical seminary. They replied that they are paid less than their male col- leagues, that many of them are not work- ing in congregations and hence have no discretionary funds, and so on. Yet when these rabbis were asked, “What if this were specifically a chair in feminist theology?” the women immediately agreed that for this idea they would stretch their tzedaka resources. Women’s philanthropy is often determined by how intimately and specifically a donor can connect to a cause.

Consonant with this, women also, according to fundraisers, ask “a million more questions” than men do….

Classically, when men give to philanthropy, they achieve status, display their success, compete with others, and gain influence in their communities. In the mid-1920s, Eleanor Roosevelt described government service in terms that apply equally well to philanthropy: “Women go into politics to make social change; men go into politics to get elected.”