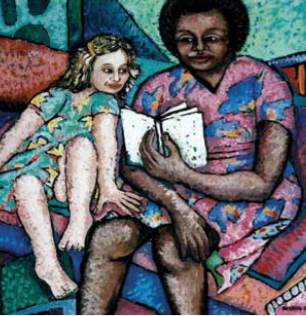

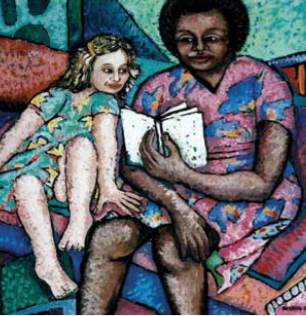

from “Jewish Girls and African-American Nannies”

Lilith asked readers to dig deep, for the first time, into these experiences. The results are stories of love and complexity. Grown-up Jewish daughters begin to think through the lessons, the gratitude and the guilt of these intensely intimate dyads. [Winter 2002–03]

Art: Jane Norman

“Thank you for triggering my memories of Mercedes,” wrote Joanne Drapkin of Bandon, Oregon. “I haven’t thought about her for literally decades. I shared a bedroom with her for two years when I was five to seven, yet I don’t even know her last name. I know I loved her. I wish my family had valued her enough to stay in touch.”

“There aren’t words to describe what Dorothy [Faust] has meant to me,” Arlene Hazelkorn of Scottsdale, Arizona, wrote. “She has given me unconditional love for the past 44 years. As a child, I sometimes wished I could live with her full-time instead of with my family. Her house was my refuge. I felt very honored grow- ing up with her, going to church, having her as part of my life.”

“Jacky Classens saved me, actually she saved all of us,” wrote Vivien Schapera of Cincinnati. “My brother’s behavior was unusual—he cross-dressed and was gay—Mom and Dad fought all the time, and I was an 11-year-old former insomniac with daily headaches and stomach aches. Jacky stilled our angry voices, cooled our pain and patched our broken hearts. Where did she find the strength?”

CLEARLY, LILITH HIT a geyser with this topic, in part because so many women were eager to talk about the African-American women who were hired to “live in” or “live out”—often a woman who was “our family therapist,” or “the one who taught me morals and values,” or “my sternest critic and my greatest defender,” or “the mother who walked me down the aisle at my wedding” —but also, as Annette Ravinsky of Turnersville, New Jersey pointed out, because “nobody ever asks us about these intimate relationships which are so devalued,” yet can be so profound.

Indeed, African-American female domestics and even nannies have inhabited one of the lowest rungs on the sociological ladder in America, and their relationships with children —especially girls, who seem to form much more intimate bonds with them than do their brothers —has spawned a literature so scant that it’s disturbing….

IN THE INTERVIEWS LILITH conducted, certain themes echoed and recurred. Many Jewish women harbored discomfort and even shame over how “one-way” their relationships had been. “I always felt guilty that I didn’t know more about Scotty’s family,” said Rachel Kadish of Brookline, Massachusetts, of Isolyn Scott.

Some of this ignorance, of course, is part and parcel of childhood: the world revolves around us, and we are largely blind to whatever doesn’t. Many women regretted that they didn’t start asking anxiety-engendering questions about race and caste and their own privilege—or even about whether their nanny had children of her own!—until they were off at college, when it was often too late.