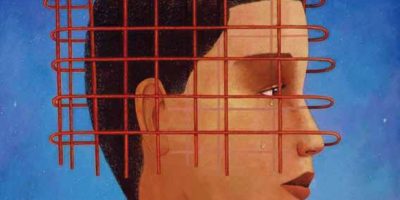

Beautiful Girl in the Snow

I recently spent several months in central china, working at a private (non-state) orphanage for very ill babies. My job was largely to care for them: diaper and feed them, play with them, put them to sleep, hold them. It is illegal to give up babies in China, so parents who can’t afford a sick child have to abandon it, usually in a public place where they hope she will be found soon. Intensively an outsider — linguistically, culturally, medically — I didn’t understand a lot of what went on around me.

What follows is a diary entry of mine from a day, a tragic one, when I found Judaism helpful.

Friday morning a two-month-old baby was left near the orphanage. She was in bad condition, so when they discovered her they brought her right to us. The state-orphanage doctor didn’t know what was wrong with her, but she was nearly gray and her breathing very labored. (There were medications left with her, but without explanation.) Here she had oxygen, a nose feed, and intravenous antibiotics. By Saturday she looked half-dead already, but I thought of people I knew who had almost died as babies, but then had made it… although I guess medical miracles are more likely to happen in hospitals, especially good hospitals. The director said that as soon as the baby — the staff named her Beautiful Girl in the Snow — could withstand the journey, we’d send her on to a proper hospital. I felt very strongly that she should be held all the time, which people agreed to. Oh, God, it’s so sad. She died late that night.

There are many, many things to say about this, but I think I will just include the little eulogy that I gave her, on our roof, where her body spent the time waiting to be taken to the cemetery (a time when, in Jewish tradition, the body is not left alone) — she was in a blanket, in a dirt-covered green plastic bin, in a red turret built for this specific purpose:

Baby, we barely got to know you at all. You weren’t even here for two days. We know you had big, dark eyes, and a strong grip, and a hard, brief life. We know the peaceful name we gave you — Beautiful Girl in the Snow — and we hope that you have found that peace. And we hope that your parents’ souls feel the peace of your soul. May you be comforted. And may they be comforted. And may we be comforted. And, baby, we want you to know that you will be remembered, if only by the handful of us who are visitors to your world, which is no longer your world.

Aside from this, which I did alone, her death was unmarked. I am very grateful for the Jewish customs around death that were automatic for me, even the formula, “May _______ be comforted.” Without these symbolic gestures, I wouldn’t know how to express my respect, distress and devotion. I sang El Maley Rachamim (a bunch of times; I couldn’t stop) before her little eulogy, inserting the surname for orphans, Beautiful Girl in the Snow bat Avraham v’Sara. And then when I saw, out the window, the orphanage director carrying her green bin away, I put a rock on the last spot I saw them.

Okay. That’s the last thing I will say about Beautiful Girl in the Snow. I’m surprised that my faith, these past two days, helped me know my place as a stranger, as a privileged visitor. I remember a friend once telling me, “Jews have often been strangers. Customs are what we take with us.”

Anna Schnur-Fishman is a senior at Brown University. She loves linguistics, writing, Yiddish, and babies. Forthcoming from Kar-Ben Publishing this fall is her children’s book about a family’s outdoor tashlich ritual, Tashlich at Turtle Rock.