About Those Canaanite Shoes That Have Been In Your Closet For 2,000 Years

Walking the narrative of Zionism

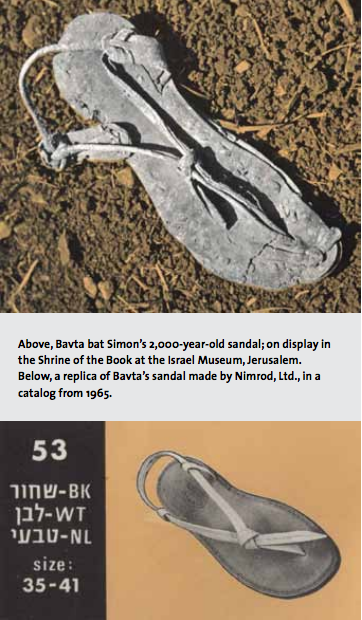

In the 2nd century C.E., a widow named Bavta bat Simon, fleeing Roman persecution, hid in a cave in the Judean Desert. She brought a lot of stuff with her to this cave — letters, real estate documents, cosmetics — and when the trove was discovered, after almost 2000 years, by the renowned Israeli archeologist Yigael Yadin in 1960, one of Bavta’s belongings — a filthy humble sandal — became instantly famous. Comprised of a three-layer leather sole held together by a spare, between-the-toes strap, it found its way into the Holiest of Holies: that is, a glass display case in the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum, where it resides to this day. [See illustration.] It also embarked on a second career traveling the world in exhibitions. So much for careers that languish for only a decade.

In 1966, five years after Yigael Yadin’s discovery of Bavta’s trove, a shoemaker and shoe designer in Tel Aviv named Josef Rosenblith (whose grandfather Zvi had cobbled shoes in Galicia, and whose father Kalman had done likewise in Poland, then Holland, then Palestine) — and who had registered a shoe company in Palestine in 1944 called Nimrod, Ltd. — published a Nimrod catalog that featured a photo of Bavta’s 2nd-century sandal as well as a photo of an almost identical sandal that Rosenblith had designed. [See illustration.]

The copy was genius: “One must admit the resemblance between this ancient sandal and those worn by the style-conscious young Israeli Sabra,” it read. Bavta’s sandal, it seems to me, could plausibly be the progenitor of shabby-chic, the fashion rage that originated in the U.S. in the 1990s.

Four years later, in 1970, Rosenblith pushed the concept further in a catalog that featured an illustration of Bar Kokhba, the famous Jewish military hero of the 2nd century C.E., wrenching open the mouth of a lion while wearing sandals. The text simply proclaimed: “From the Land of the Sandal.”

Rosenblith, who at some point changed his surname to Ben Artzi [“Son of My Land”] and then just Artzi [“My Land”], had essentially “branded,” through the marketing of a shoe, the narrative of Zionism and its linearity: from the foundational myths of the biblical era, through the abject centuries of Jewish exile, and finally to the triumphant return of Jews to Palestine and that real estate’s kinetic, teleological evolution into the sovereign State of Israel. All a shopper had to do — to find and assert her rightful place in this grand, sweeping arc of history — was buy a pair of sandals.

Tamar El Or, an anthropologist at Hebrew University, writes about the “biblical sandal” in an article in The American Anthropologist. Growing up in Tel Aviv in the 1950s and ‘60s, El Or states that Nimrod sandals were part of her everyday attire, but El Or’s ethnographic research, for 25 years, concerned “narratives” — the stories of Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Israeli women — not “material culture.” In the early 21st century, however, anthropological scholarship took an “ontological turn” towards the study of objects, and El Or suddenly looked down and saw that what Israeli women put on their feet, and have for decades — well, actually for millennia — was worthy of study.

She devoted three years to researching and assembling the object’s biography: from studying the history of footwear in the ancient Near East, to reading canonical Jewish texts, and even to taking a footwear-making course at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem.

Mostly, though, El Or focused on interviewing the members of Josef Rosenblith’s family, as well as designers from the family’s company, Nimrod. The company has no official archive, but Josef’s descendants — Oren, Liora, and Tzafi — were happy to open disorderly kitchen drawers and unpack random boxes in attics to unearth photos, newspaper clippings, personal documents, letters, and catalogs. Though El Or’s work was scholarly and therefore, she felt, should be approached with curatorial gloves and frowning-brow inquiries, the truth was, she says, the process was spirited, with Josef’s progeny turning out to be warmhearted, open, and fun.

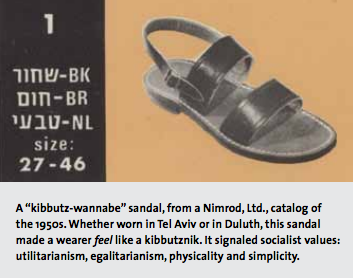

Jewish sandals, it turns out, were first produced in Palestine on kibbutzim in the early 1930s. The Mediterranean sunshine, kibbutzniks’ limited financial resources, and the reigning socialist ideologies — utilitarianism, egalitarianism, physicality, and simplicity — made the invention of these sandals seem almost ineluctable: conventional shoes, after all, were overwrought for the kibutzniks’ lifestyle and purposes, and thongs (or flip-flops), the ultimate reduction, were uncomfortable for wear over socks on cooler days and inappropriate for physical labor (though they were good, as are most sandals, for shaking your foot and easily dislodging stones or sand).

This “kibbutz sandal,” though, was not like the between-the-toes-strap sandal of Bavta bat Simon. Instead, it was made with horizontal straps — two of them — with a third, thinner strap that wrapped around the ankle. [See illustration p. 34.] This sandal became the dominant mid-20th-century style, though it carried, unlike Rosenblith’s Bavta-like design, no historical resonance — at least not in Palestine (or later, Israel). Conversely, in Central Europe, an almost identical style was a known form called the “Jesus Latchen,” which certainly suggests that biblical-origin thing.

On the kibbutz, the eponymous sandal was, simply, exactly what it was: footwear that resident shoemakers made and resident kibbutzniks wore because there were no alternatives. The kibbutz sandal also became de rigueur for some folks who didn’t live on kibbutzim — children in Jewish socialist youth groups, for example. The sandals became a core component of an aesthetic and “dress code” that advertised and endorsed a young person’s intention to become a kibbutznik at maturity.

When the Rosenblith “shoemaking dynasty” fled Holland and founded Nimrod, Ltd. in Tel Aviv, the family noted that these kibbutz sandals could be given a new and different value. The kibbutzniks had a need for these sandals, the Rosenbliths observed, but Tel Avivniks could develop a desire for them. In the late 1950s, Nimrod started making horizontal-strapped “kibbutz”-wannabe sandals for Israeli urbanites, and even tourists.

The dominant ideology in Israel in this era belonged to the socialist pioneers and was accepted as superior by the majority that did not live off the land and were not even necessarily socialist in political orientation. Nimrod’s “kibbutz sandals” became an object of the admired “them” — the minority who led the “right” kind of life.

The aesthetic of the two brown straps began to signify the ethics of kibbutzniks — an idealized, romanticized “other.” A simplicity was transferred from the field to the sidewalk and became a desired cosmopolitan object. The sandals allowed the Jewish wearer to remain in Tel Aviv (or in New York or L.A. or Miami Beach, or even Duluth, for that matter) and suddenly look or feel like a kibbutznik, signaling, via his or her feet, an affiliation with a deeply held value or with an aspiration or experience or loyalty, or even just with something that felt cool.

Once the Rosenbliths figured this out in the 1950s, it was pretty much a snap, when Bavta’s 2000-year-old possessions became the stunning archeological find of the 1960s, for Nimrod, Ltd. to extend its understanding of “desire.” Their new design — horizontal straps now sleeked into verticality — connected wearers not only in space, but in time as well: all the way to antiquity.

Even the name of their company — Nimrod — Tzafi told El Or, was chosen with an ear and eye to subliminal marketing. “In Holland there was a shoe company by the name of Robinson Crusoe,” Tzafi said. “[My dad] searched for a parallel figure, a cultural hero of nature. He chose Nimrod, the biblical hunter.” Bavta, Bar Kokhba, and Nimrod, then, had semiotic oomph, unearthing consumers’ “desire.

Recently, El Or writes, she found herself craving “a pair of Nimrod sandals, an original pair from the classic era. On eBay, I find someone in New Jersey with a pair for $50. I buy it. I am now the owner of that thing, not the one I actually wanted, not the two vertical straps, another model, a man’s style, which I never liked. But I have it.”

She wonders: “What makes something a commodity, an item to be put on eBay almost 40 years after it was produced in a remote Middle Eastern country? Why did its owner think he could sell it or assume that someone would want it?” El Or notes that culture and politics “create the concept of the thing,” but she accords primacy to “the desire to possess the thing”…the desire to have something, “that’s what reigns uppermost,” she says.

On the other hand, the scholar David Ohana, El Or writes, places the “utopia of Nimrod” as “central to the constitution of ‘Hebraic authenticity’. He describes a cultural project of creating the first generation of natives in the land of Israel in the shape of a ‘warrior and not of a scholar, to offer experience rather than knowledge, aesthetics instead of ethics, and myth rather than historical recognition’.”

In Israel, El Or writes, “Some will go to great lengths to find these lost sandals that no one wants to produce anymore. Their desire will take them to shanti stores (what are called head shops in the United States) in Tel Aviv, where Indian clothes and footwear are sold along with leather sandals made in Hebron, Palestine.”

More modern adaptations exist, of course. Young women “might trade the flat rough sole for the rubber one with good grip and buy sandals from the firm Source.” Older women “might choose a comfort sole made by Naot, but all of them will look down at their feet and see two straps”…and a whole lot of foot.

The art historian and curator Gideon Ofrat disagrees with El Or’s understanding of the continuity, authenticity, endurance and “emotional resistance to change” that inheres in these particular, foundational objects — both the Bavta Bat Simon sandal and the kibbutz one — and that continues to represent something perceived and experienced as “true.”

“In 2007, huge ads were hung on bus stations promoting Nimrod shoes,” Ofrat writes. “In the center stood a well-groomed Israeli youth, dressed in fashionable brands and wearing Nimrod shoes, of course. This spoiled, urban, up-to-date, well-off child of the 2000s is the great-grandchild of the mythical Nimrod.” But between “today’s consumer and this consumer’s great-grandfather,” Ofrat argues, “nothing in common remains.”

El Or disagrees. Whether it’s the eBay hunter, the shanti store haunter, or the Lilith reader who finds herself, as I did, mesmerized by Bavta’s 2000-year-old sandal in the Israel Museum display case or even by the photos accompanying this story, the “young brand lover,” says El Or, definitely has “something in common” with her mythical great-grandmother.